Citizenship by Investment 1.0 is Dead – Long Live Citizenship by Investment 2.0

Greco’s Geopolitics

With Brian Greco

With an eye to the changing world order, Brian Greco explores how individuals can get and keep global access.

The citizenship by investment industry was the natural product of a nascent globalizing world. It all started in the 1980s when borders were beginning to blur: Capital and people were beginning to fly around the globe at a pace never before seen. Travel became more possible than ever. Business was truly multinational.

This raised a core problem: The power that historically “gate-kept” access to highly desirable destinations, opportunities, and financial services was predominantly found in the hands of those who held certain identities.

Overwhelmingly the identities favored were Western ones; those affiliated with the former Anglo-world order (US, Canada, UK, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand) or those in the greater European life space—Europe itself, or many of its former colonies with stronger passports, including many in the Americas.

A handful of small countries we all know and love, specifically in the Caribbean, realized they were sitting on a great opportunity.

Birth of a global industry: citizenship as commodity, passport as product

What does a wise country with no significant population or natural resources do in a globalized world? Set up its jurisdiction in the most appealing way possible to promote business. Thanks to RCBI, no country has an excuse to remain poor without something to offer the global system.

A passport was the key to what people wanted, particularly three things:

- privacy under a renewed identity

- visa-free travel to the West, and

- freedom from what I'd call "excessive taxation, bureaucracy, and hassle."

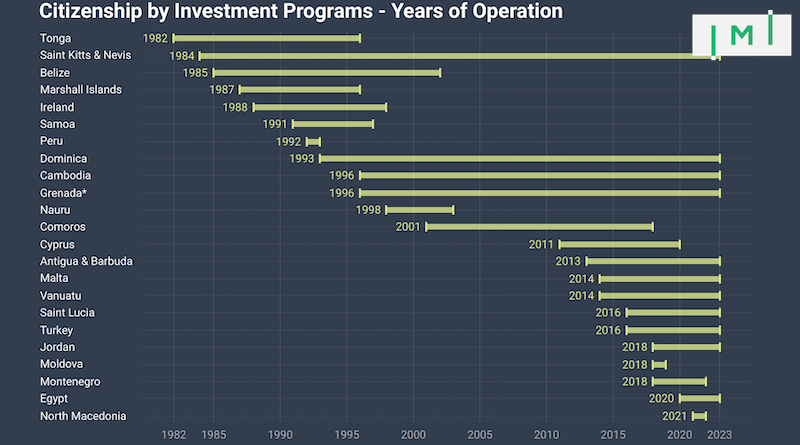

Out of these motivations, many programs were born. Respect must first go to St. Kitts & Nevis, the godfather of citizenship by investment, whose program is the longest-standing and ultimately the original form of true direct citizenship-by-investment in 1984. (Tonga and others tried before and after, but St. Kitts' was the first real program and the clear first in the Caribbean, followed by Dominica and Grenada—you can see a full history timeline here.)

Last of the independent Caribbean states to declare independence from Britain in 1983, St. Kitts & Nevis hit the ground running and understood the assignment. It was the perfect moment to capitalize on one of that small island economy's most valuable assets—its citizenship and all the rights, protections, and privileges that came with it.

An industry was born: Right need, right time, right offer. Clients were beginning to get what they wanted without the uncertainties of traditional naturalization and all the investments of time, money, and energy normally associated with it.

Give clients what they want, and earn big — imagine that

Clients wanted to be part of the Commonwealth and go to the UK, and they got it. Clients wanted access to Europe; they got it. Clients wanted Canada; they even got that too (and then lost it, and then gained it back, sort of). And money was pouring into economies that needed it. It was truly the win-win-win of the century.

Remember, new investor citizens didn't just want to travel—they wanted the gatekeepers of desired institutions to perceive them in a completely different way. Opening a company as a Nigerian citizen? Banking as an Iraqi? Trading in and out of Iran? Easier said than done with certain identities. But CBI could solve it all, almost.

Obviously, nothing that simple ever lasts. CBI experienced its share of hits as time went on. Everything easy goes away eventually and gets more complicated. The glorious era of 1990s Hong Kong companies, easy zero-tax residencies, and blissfully efficient dealings couldn't last.

For example, Belize, a perfect jurisdiction for a CBI, closed its program under pressure from the US following the events of 9/11, which of course marked the beginning of the modern "surveillance capitalism" we now know and still deal with.

The KYC panopticon only grew deeper as the digital and smartphone era began to take hold in the late 2000s. Admittedly, some of it was probably needed—the industry could not manage long-term growth unless it was managed properly.

Realizing the goalpost is always moving and the carrot is never coming

Few would oppose proper due diligence protocol or stakeholder engagement, which protect a nation's integrity and a program's reputation. But we all know that something has changed and that it goes far beyond these basic tenets. It was plain to see something big was finally boiling over when the “6 CBI Principles” came forward in March, a "cringe-worthy" document given that - last time I checked - the Caribbean countries in question are neither colonies of the United Kingdom anymore, much less of the United States.

First, they came for Vanuatu, but I did not say anything, for I was not ni-Vanuatu. Many saw it as an easy target or perhaps a harbinger. Just a few weeks back, we saw the UK’s first overt visa suspensions in quite some time come down against a vulnerable island nation Vanuatu as well as Dominica, their next easiest target.

And now the inevitable has come: Talk of complete EU visa-free suspension of Caribbean CBIs has upended the whole field. St. Kitts’ cryptic announcement this week resulted in doubled minimum investments and a slew of new regulations, and others may follow.

Anyone with any clarity on the constantly moving goalposts of the European Commission, the sworn enemy of global mobility, knows that this charade has long since ceased to have anything to do with due diligence or realistic concessions. The European Union's hypocrisy for complaining about well-vetted, wealthy immigrants coming through "backdoors" means nothing with even the most cursory look at their "front door barely guarded".

When we have reached a point where normal naturalization is almost more attractive and efficient than CBI itself, we have lost the way.

Retaining the core value proposition of CBI itself is existential to the survival of this entire multi-billion dollar industry and all the people and places it supports.

So what happened here?

Problem 1: Losing sight of the foundation of privacy

The foundational raison d'etre of wealth planning is protecting the privacy of clients. In a world where everything is trackable and traceable, many people choose to turn to citizenship by investment to obtain more optionality on the long-lost art of privacy.

Privacy does not mean fraud. Privacy does not confer illegality. Privacy does not require "secrecy". Privacy includes many things, including the right to change or choose your nationality, conceal personal information from public prying eyes, and even sometimes to adjust elements of your identity like your name, livelihood, and whereabouts.

Once you begin to factor in the weight of all the onerous and lengthy requirements for due diligence, the random addition of physical presence stipulations, the personal interviews of questionable utility, and several other constantly-evolving definitions of “genuine links” or “proper vetting”, the whole notion of privacy begins to degrade, and clients don’t like that.

Remember, Turkey’s highly misunderstood program is the world's best-selling CIP, not simply because it was well-priced and fast or some kind of “Plan B” consolation for those who couldn’t do otherwise. It doesn't even have access to Schengen! And the program still blew the competition out of the water (see below).

Underrated about Turkey’s program is the ability to choose a new name—a Turkish one, standard practice in Turkish society—which gives people a chance to adopt an entirely new frame of ownership and mobility. Moreover, the ability to purchase CBI real estate using cash or other assets that aren’t overly scrutinized to the point of insanity was a fan favorite. Remember that beautiful world we are trying to protect where people are free to use, invest, and transfer their property freely amongst each other?

Problem 2: Drooling over the holy grail of Schengen Access: But why?

I've written before about this topic and have developed a small bit of niche notoriety about asking the question: "What's so great about Schengen Area?"

But the point today is not whether you or I personally like traveling to Europe. It’s about whether this feature is the most important (or, for some people, the only) reason to market or buy citizenship by investment.

True “visa-free” Schengen access itself is in any case about to sunset with the introduction of ETIAS, a sort of electronic pre-authorization not unlike that of Australia’s ETA or America’s ESTA. Remember: true visa-free travel died after COVID-19. If you need to present a pre-authorization or paperwork at the border, that's called a visa.

Regardless, shouldn’t anyone with US$150,000+ (and now potentially US$250,000+) to their name who passes extensive due diligence be more than able to obtain a Schengen visa or any visa they want? I have heard many with far less get far further than that. Visa-free Schengen in 2023 isn’t make-or-break for anything - or at least it shouldn’t be.

In some ways, the UK is harder to enter, measured purely in the number of nationalities it permits visa-free. And while its complaints have been more recent under the guise of a peculiar anti-wealth trend (including the closure of the Tier 1 Visa in 2022), those complaints have begun in earnest, and we can expect them to go in line with the tone of the EU and the US.

Like it or not, Europe is economically and demographically in decline. The nexus of global momentum is no longer there. This is not the Europe of the 1980s. While this is a topic for another day, I'd like to remind the reader that just as it was CBI sellers who manufactured demand for Europe, they can also manufacture (or unearth latent) demand for other regions given the chance to show their economic prospects and lifestyle chops.

Europe is not the only center of excellence globally, nor is it always the best value for money or the best friend of mobility. Just look at the neverending circus of the Portuguese Golden Visa’s deliberate and self-imposed “reputation ruination” and you will be reminded.

Problem 3: The rapidly diminishing utility of CBI to avoid excessive taxation, bureaucracy, and hassle

I think this one is pretty self-explanatory. Gone are the days of most truly tax-free nations with zero graylists or blacklists, let alone ones that you can easily bank from, open companies in, or do global travel and business as a citizen of. CBI was supposed to be about ease but, as I said earlier, we have reached a point where normal naturalization has almost become more attractive for the reason of avoiding hassle or skepticism alone.

My take? Any family from the Chinas, Indias, and Russias of the world with any serious money and serious take on citizenship already knows from seeing these reputation-threatening trends that CBI in its 2023 form is not their ticket. Any Hongkonger who saw the writing on the wall in the 1990s already obtained Australian, Canadian, US, UK, or similar citizenship years ago and has few worries of border patrol accusing them of “not having genuinely obtained” those citizenships.

Expect a full-circle return to old-school naturalization or consistent high-demand programs like EB-5. Or maybe some savvy investors and advisors that serve them will choose to pursue unique, lower-profile pathways to naturalization in countries like Chile, Brazil, Argentina, or even the Balkans or Middle East, with equally or often more powerful passports that are multi-racial in makeup and highly unlikely to lose any kind of travel access.

Never underestimate the customer experience hit CIPs take when processing times get lengthier. Never mind the hassle of having the European Commission and the judgmental “international community” immediately detect your citizenship as “bought”.

The word got out over time, but there was no real retort to make the case for CBI as a net good. Where was the lobbying on that, except for that laboring under EU-fed framing? There's no room to focus on overcoming problems when you are perpetually seeking to cozy up to the voices creating them.

What's the path forward?

Enough with the Stockholm syndrome: It’s time to end this dysfunctional relationship. While the EU/UK access has been a core part of CBI’s product and international relations strategy, this can change, and products can always innovate. The EU, and to a lesser degree the UK and the US, form the number one threat to the citizenship by investment industry. Most of the ensuing mess is due to perpetual reactionary attempts to heed a list of ever-changing demands.

Caribbean CBI nations are sovereign countries, and CBI has played and should continue to play an important part in fully emancipating them from former colonial powers. Yet, here we go again, learning the lesson all over again that the Global South rarely ever wins by listening to overseas unelected bureaucrats telling them how to run their affairs.

This industry needs innovation to deliver what people want: Clients want passports. Advisors want products. Governments want funds.

Let's get back to basics. It's time for a total reset.

In my next article, I hope to explore what a Citizenship by Investment Industry 2.0 might look like and how we can take what has worked and create anew.

Brian Greco is a traveler, cultural explorer, and advocate of free movement and the investment migration industry based in Istanbul, Turkey. Originally from the USA, Brian has a background in globalization studies at New York University and experience living in Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe and traveling solo to more than 75 countries. He focuses on investigating and promoting new possibilities for expanding lifestyles in global cities, especially in frontier markets. Brian is a believer in the power of discovering the lesser-known path in life and using travel as a tool for personal growth.