Opinion: Citizenship by Investment’s Role in Finally Emancipating Former Colonies

Opinion of the editor

Citizenship by investment has granted small, developing countries in the Caribbean and Pacific the means to fund public spending independently, rather than rely on outside aid or loans. That financial autonomy reduces the influence developed countries have in these jurisdictions, which is one of the reasons they seek to restrain such programs.

What does it mean to be a sovereign country?

To be an independent country, it’s not enough to have your own flag, currency, football team, and national bird. You can even have your own military, courts, and police and still not be independent, because as long as someone else is paying the piper, someone else is calling the tune.

To be truly independent, you must have your own source of income.

A genuinely independent country can determine its own domestic policies, even when bigger, richer countries don’t like those policies, because it has independent means and isn’t threatened by the withdrawal of financial assistance.

Every continent in the world has vassal states that are formally independent but whose governments are de facto reliant on – and, therefore, obedient to – more dominant states.

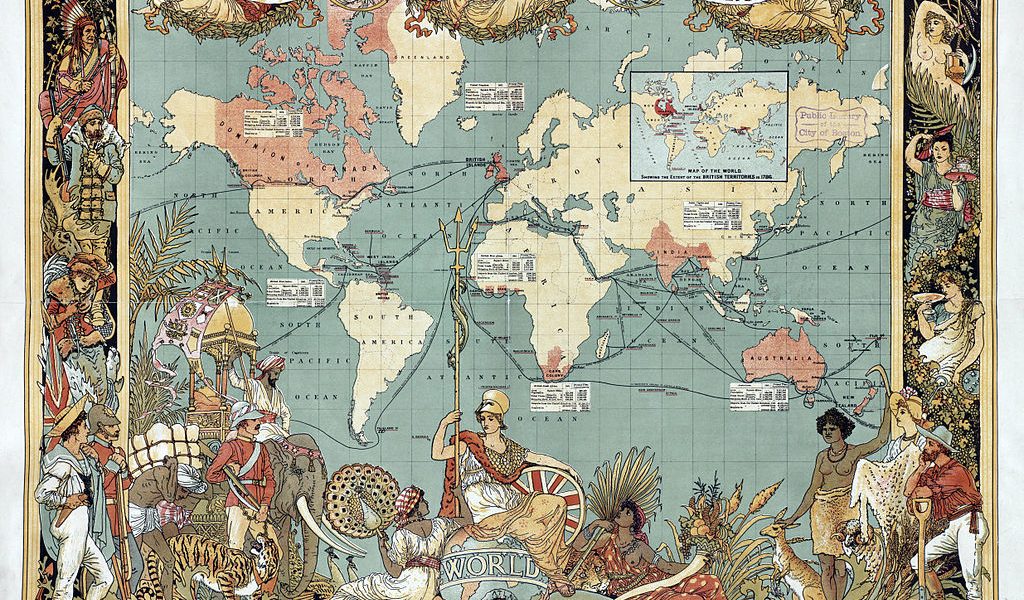

In the late seventies and early eighties, many countries in the Caribbean and the Pacific gained independence from the colonial powers that had ruled them – chiefly Britain – but were not sufficiently industrialized to finance their own governance. Much of their budgetary spending since then has been financed by loans or aid from developed countries.

This inevitably granted their creditors some significant degree of clout, also as concerns domestic policy. It meant that these countries frequently had to listen to the advice (if advice that must be taken can even be called ‘advice’) of external governments not elected by the local population.

But over the last decade, a growing number of former colonies have begun to tap into a resource that had laid dormant for most of their histories; citizenship by investment, a wellspring of unencumbered, interest-free capital.

A Farewell to Alms

Citizenship by investment grants these small countries actual independence, because they no longer need to rely on handouts from developed countries or loans from the IMF or the World Bank,

With a CIP, they needn’t beg, borrow or raise taxes to fund their operations. Chris Kälin has coined the phrase “sovereign equity” – as opposed to sovereign debt – to describe the phenomenon of governments paying their bills and reducing their debt-burden by taking in voluntary contributions from prospective citizens.

Countries that can fund themselves are countries that can say ‘no thank you; we can shape our domestic policies on our own just fine”. And this is of grave concern to certain quarters in the developed world.

The Organization for Economic Coercion and Disenfranchisement

The OECD, lofty mission statements notwithstanding, is essentially a special interest organization for high-tax, rich-world countries. They ostensibly oppose citizenship by investment programs out of a misconceived notion that they are used to evade tax – which is not the case, as tax is levied based on a person’s physical residence, not their citizenship (except in the case of the US and Eritrea).

See: OECD Issues Paper on “Preventing Abuse of Investment Migration Programs” for CRS Circumvention

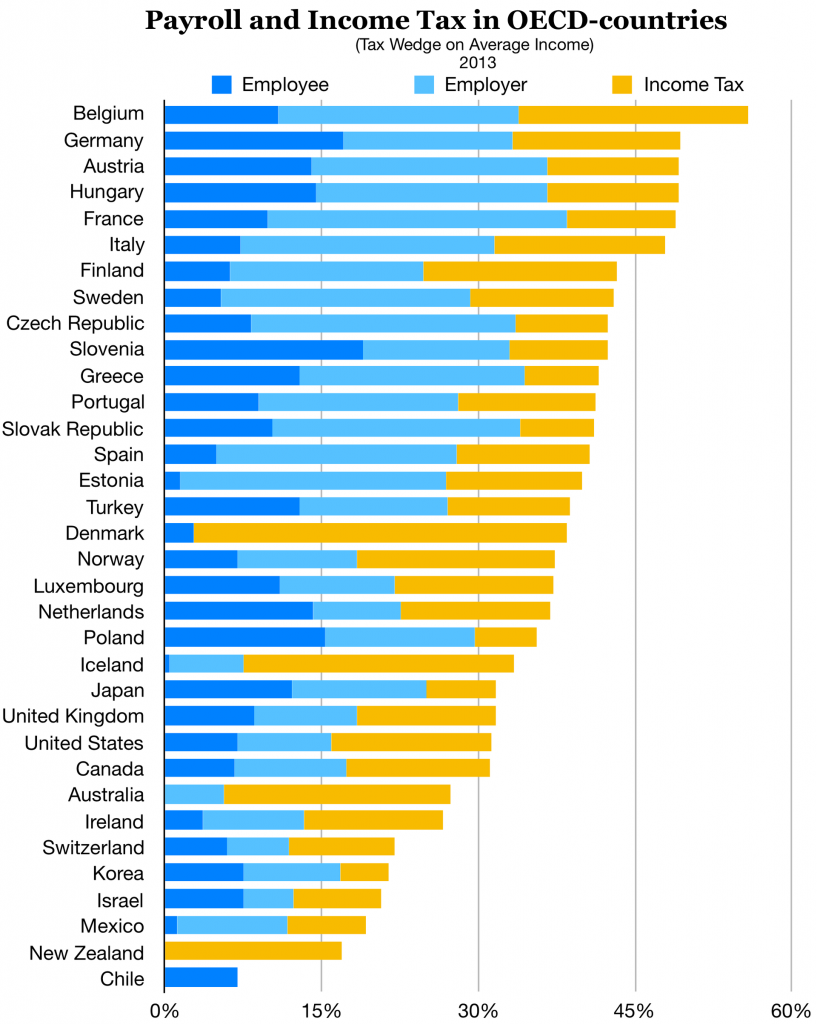

Small, developing countries like those in the Caribbean or the Pacific have very few competitive advantages in the world economy; their markets are minuscule, they don’t have much in the way of natural resources, and they’re not strategically located along major trade routes. To compete for capital investment with the big, developed countries of the OECD, therefore, they typically use the one advantage available to them by virtue of their (nominal) independence; they offer attractive tax environments for companies and individuals, with rates far below the OECD average.

See also: Burke Files: OECD-Countries Themselves are the Main Beneficiaries of RCBI-Programs

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the sharp fall in average tax rates in OECD countries during the early eighties coincided with small Caribbean and Pacific islands nations gaining independence from their European colonies; within the span of a decade, dozens of newly minted states appeared on the world map, offering virtually tax-free ecosystems. The very existence of these jurisdictions quickly became an effective counter-balance to the avarice of rich-world governments.

This is a real pebble in the OECD’s shoe; if it weren’t for those pesky little beach-with-a-flag jurisdictions offering people and firms an alternative, OECD-countries could squeeze a lot more from its own HNWIs and companies.

But, of course, the members of the OECD, which include virtually all the former colonial powers, can’t be seen to dictate the domestic policies of their former colonies because, you know, they’re supposed to be independent now, and that would be tantamount to neo-colonialism.

So instead, they seek to influence these countries’ domestic policies (particularly as they relate to tax) by surreptitious means; by placing these countries on blacklists for engaging in what they euphemistically refer to as “harmful tax competition”.

Harmful to whom? Not to the individuals and companies sending their capital to the Caribbean; certainly not to the Caribbean recipients of FDI. What they mean – but won’t say – is that it’s harmful to the governments from which capital is departing to seek refuge elsewhere, i.e., the OECD-countries themselves.

See also: IMC to OECD: Singling out RCBI-Countries “Makes No Sense and Cannot be Justified”

and: PM: Antigua Will Amend Laws to “Keep Out of the Crosshairs of the OECD”

The (anything but) SWIFT system

The means by which the US has weaponized the SWIFT-system against those unwilling to toe the geopolitical line drawn by Washington has been the subject of a great deal of writing in the last 4-5 years. The Russians, Chinese, and Iranians are all intimately acquainted with attempts to stymie their access to international banking channels. The US controls the SWIFT system, which is meant to facilitate international bank transfers, but which can just as easily be used to obstruct them.

In the case of “rogue states”, such measures are explicit. In the Caribbean and Pacific, on the contrary, the SWIFT-system isn’t used for overt opposition but, rather, for subtle subversion with plausible deniability.

What happens in the Caribbean, for example, where five of the most prominent CIPs are located, is that those intermediary banks in the US delay the investment payments of CIP applicants on – usually very thin – KYC/AML pretexts. So an applicant from, say, Khazakstan, who has undergone months of background checks, due diligence, and screening to be approved for citizenship by investment in, say, Grenada,

Considering the screening the applicants have already undergone to qualify for the CIP – a screening that is many times more thorough than any KYC/AML a bank does – this is not at all justified and actually represents a major infringement on the rights of that client, as well as on the sovereign right of that country to do business with whomever it pleases. It further makes it very difficult for those Caribbean countries, in general, to engage in international trade.

To mitigate this predicament, Caribbean countries have increasingly seen it necessary to find alternative methods of sending and receiving international payments. Antigua & Barbuda, for example, has begun to accept Chinese RMB (which uses China’s home-grown alternative to the US-controlled SWIFT system) and cryptocurrencies.

You can see my interview with the PM of Antigua & Barbuda from January where he laments this state of affairs. When borrowing capital in international markets, Caribbean governments are compelled to pay usurious rates of up to 10%.

“You can pick any color you like, as long as you pick black”

The abovementioned subversive efforts constitute a grave and widely ignored injustice. The OECD and the US are actively thwarting the flow of capital to tiny developing countries, imperiling what, to many of them, amounts to their single biggest source of revenue, all because these countries’ CIPs threaten the indirect influence the OECD/US/IMF/EU have on domestic policy in the region.

On paper, the developed countries relinquished control of their colonies decades ago; in practice, when the newly independent states implement what their former masters deem inconvenient policies – which, mind you, is their sovereign right – the former rulers do all they can, short of direct intervention, to force them to conform to their preferences anyway.

In 1909, questioned as to whether his customers could choose the color of their Ford Model Ts, Henry Ford famously answered that “any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants, so long as it is black.” In the Caribbean and the Pacific, purportedly sovereign states can have whatever domestic policies they want, so long as they don’t conflict with the interests of their former colonizers.

If these countries are only free to set their own tax rates, determine whom they naturalize, or with whom they trade as long as it is acceptable to the governments that used to own them, how independent are they really?

The tiny island nations of the Caribbean and Pacific are either independent, or they are not. If they are independent, let them choose their own domestic policies. If they are not, then come out and say it; you still want to run them.

By Christian Henrik Nesheim,

Editor

Christian Henrik Nesheim is the founder and editor of Investment Migration Insider, the #1 magazine – online or offline – for residency and citizenship by investment. He is an internationally recognized expert, speaker, documentary producer, and writer on the subject of investment migration, whose work is cited in the Economist, Bloomberg, Fortune, Forbes, Newsweek, and Business Insider. Norwegian by birth, Christian has spent the last 16 years in the United States, China, Spain, and Portugal.