Why Those Hoping to Design CIPs in the South Pacific Are in For a Ride

Due Process

With Michael Krakat

Legal Scholar Michael B. Krakat observes investment migration through the lens of international, constitutional, and administrative law.

Edited by Christian Nesheim and Ahmad Abbas

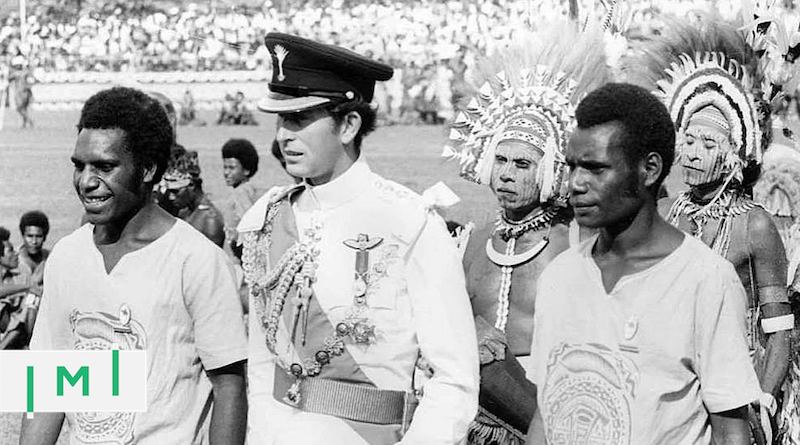

When creating CBI programs in the South Pacific, policy- and lawmakers, as well as advisers, need to take into consideration a variety of regional idiosyncrasies that they’re not likely to encounter in equal measure elsewhere. In the South Pacific small island states, Western notions of nationhood, nationality, and citizenship are interpreted, perceived, and ranked differently than they are in the cultures in which they originated.

In his seminal 1983 book, Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson was the first to adopt what has since become a common academic characterization of the concept of nations: Invented, ideological, and historical fictions (“imagined communities”). While the Western (read: Westphalian) idea of the nation is founded on precisely those fictions, the same concept in the South Pacific may have an entirely different meaning. And that had consequences for those seeking to establish citizenship by investment programs in the region.

While the legal concept may be the same or similar, the South Pacific interpretation of nationality and citizenship grows out of collective, historical experiences that are entirely distinct from those in Europe or North America. Distinct how?

First, unlike Europe and North America, the South Pacific region contains far more ocean than land. Its cultures are scattered across the seas and have, in many cases, developed with only limited interaction between each other. These cultures are, thankfully, not comprehensible or expressible through legal-political principles and doctrines alone. Nationhood, here, did not evolve in a linear fashion, as emulations of development-paths in other regions.

Citizenship as a legal “transplant”

Independence for most island states in the South Pacific came about during the same period in which similar developments took place in the Caribbean; The 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. The newly independent countries needed laws and were not inclined to reinvent the wheel entirely. Instead, they typically adapted, and then adopted, much of the legal framework inherited from the colonial powers, anachronistic vestiges of which remain in place.

Along with that inherited legal framework came the Western legal notion of ‘nationhood’. It had not arisen organically in the Pacific but, instead, reflected particular historical paths taken in Europe. Nationality laws in the South Pacific were transplants, taken from the European body of laws, airlifted to remote islands in the hope that they would assimilate with the local fabric of laws, customs, and cultures.

But the nature of transplants is that they don’t always match the recipient system. I propose that, since the transition to independence, the South Pacific’s concept of nationhood has metamorphosed into a concept in its own right, one that is more flexible than it is elsewhere and that, thanks to an infusion of local culture, has not fully adopted the same metes and bounds.

If this hypothesis proves correct, and experience tells us it should, CBI planners over here are in for a ride.

The nation-building exercise in the South Pacific is still ongoing, which partly explains why the practice of CBI has yet to fully settle in the region as well. Only one of the region’s states – Vanuatu – has active CBI programs, but many, perhaps most, have specific CBI plans on the drawing board. These planned programs are completely revised, revamped, and reconstituted from the shadows of the region’s proto-programs of the past.

See also: The Bizarre Story of How the King of Tonga’s Court Jester Lost $26 Million Made from Passport Sales

However, history repeats itself, and it is not entirely certain that past mistakes and issues have been completely resolved, nor – indeed – whether they are even resolvable.

The interchangeable use of the terms citizenship and nationality has been around for a long time. Technically, citizenship outlines the municipal sphere, while nationality describes the international law dimension of the connection between the citizens and the state. Today, they usually fall together, and the reasons for this are complex.

In a constitutional-legal (and somewhat tautological) sense, countries grant citizenship to those who fulfill the formal legal requirements, warranting a look behind the veil of who the people for whom the elusive concept of citizenship applies are.

Anyone is principally free to purchase a passport subject to certain standards, including fulfilling criteria such as due diligence checks. Whether nationhood is a static concept fulfilling the same expectations and core functions it may do in other places is the real question.

Just as CBI is a formal, legal, and transactional practice, it may still evolve into something else. The concept of nationhood in the South Pacific appears as a formal and legal one, as constitutions and their preambles outline, to some extent, the metes and bounds.

The level of material definitions assigned to the concept is sometimes unclear, which leads to ambiguities, fragmentation, and incoherence. This lack of clarity affects the meaning of CBI as well as its planning and structure.

Citizenship is a concept that exists on paper within the confines of the law and in the people’s imagination, the latter being what people believe the law should contain. This conflates citizenship’s moral and political aspects and highlights the difference between what is and what should be, a premise at the heart of the concept, resulting in many misperceptions between what citizenship should morally mean and what it politically and/or legally means. In other words, the legal infrastructure or matrix of citizenship may vastly differ from its political or moral narratives associated with that legal lens.

The concept of nationality in the South Pacific is sometimes viewed as a local mystery, although it should not be enigmatic. Vanuatu’s CBI experience provides a more holistic view through valuable contributions and observations of expert onlookers.

What actually constitutes a nation in the South Pacific paradigm emphasizes all government structures along with a strong focus on local political stakeholders, based from the ground-up, of customary cultures of local chiefs, traditions, family structures, networks functioning, and taking responsibility for local council.

Local rule defined the Pacific experience for millennia, and it contained conflict to a local level while maintaining the general absence of need for higher ordering principles of power. Unless, of course, a uniform voice of the people emerged and spoke as one, which is challenging to achieve.

This structure reminds us of the principle of subsidiarity, addressing matters on the level of governance where they fall due, before the escalation to a higher rank of power, such as the national level, is required.

The need to define “nation”, in the Pacific, came only after the encounter with other nations

It is no surprise then that the emergence of a nation in some Pacific Nations such as Samoa was first related to other states. The necessity to define the country through a unified view in regards to other states was evident.

To understand the meaning of ordering paradigms such as that of nationhood, we need to go back to the pre-colonial and colonial periods.

Colonial discourse (such as Sylvia R. Masterman, with The Origins of International Rivalry in Samoa, 1845-1884, 1934: 194) was adamant that chaos would ensue after colonial rule:

‘We have seen the islands […] pass from a state of primitive but happy disorder to a condition of semi-civilized but unhappy confusion […] until the bewildered Samoan chiefs, distraught by intrigues, begged that the burden of government might be lifted from them.’

The meaning of nation – and the derivatives of nation such as nationality and citizenship – in the Pacific perspective is closer to what Ton Otto and Nicholas Thomas poignantly describe in their work Narratives of Nation in the South Pacific’ (1997, 4):

‘Once independence had been gained […] the fundamental opposition between indigenous people and colonial powers was displaced by a far messier array of local divisions, relating variously to pre-colonial antagonisms between different indigenous populations, the simultaneous exacerbation of conflict and suppression of warfare during the colonial period, uneven development and corruption.

The most obvious expression of this is the Bougainville War, but many more localized or primarily non-violent conflicts could be noted, in most other Pacific states.

While a historian or anthropologist could unambiguously endorse the movement towards independence, and take continuing colonial hegemony to be immoral, there is no obvious stance and no wide agreement (neither among scholars nor within the countries concerned) about Bougainville separatism, the factional struggles within the Vanuaaku Pati, or the postcoup regimes in Fiji.

If many anthropologists would empathize with the aims of the pro-democracy movement in Tonga, they might do so uneasily, only too aware of the degree to which democracy has promised so much more than it has delivered in other parts of the world.’

Liberal scholars typically support self-determination for indigenous peoples and advocate an autonomous nationhood. The idea of autonomy implies that ‘indigenous’ is itself an unproblematic and settled category on which a better nation would be able to rest.

The very concept of indigenous status is often viewed as limiting, leading to further issues. Given the emphasis on local customs and precedence, it is likely that even the pre-nation state constructs of cultures predating colonization were ambiguous and politically contested, not settled.

Simple and insubstantial anticolonial posture, while necessary, is insufficient to constitute decolonized history. The replacement of colonial power did not come with swift alternatives, as independence came through struggle, willpower, and tears.

The question here is, were the pre-colonial experiences and the superimposed concept of nationhood already incoherent and incompatible?

As Otto and Thomas assert, independence has at times led to centralizations of power and sometimes escalated isolated local conflicts to the national level. The result is the ongoing incompatibility of nationality in its implementation compared to other states of the world.

The construction of the island – as well as all histories – is an inherently political matter. The time needed for establishing CBI in all Pacific domains is open for conjecture, mainly because the definition of nationhood itself is still an unsettled matter.

End of Part I.

Michael B. Krakat is a lecturer and coordinator for comparative Public law – International, Constitutional and Administrative Law – at the University of the South Pacific at Vanuatu and Fiji campuses. Michael is also a researcher at Bond University – Queensland – and Solicitor at the Queensland Supreme- and the High Court of Australia. He also is an academic member of the Investment Migration Council. He can be contacted at michael.krakat@usp.ac.fj.