Remembering the Dead Part 2 – Citizenship by Investment Programs of Yesteryear

This is the second in a two-part series on now-defunct residence and citizenship by investment programs. This week, we look at citizenship by investment programs that are no longer with us. See Part 1 here: Tajick: Remembering the Dead Part 1 – Residence by Investment Programs of Yore

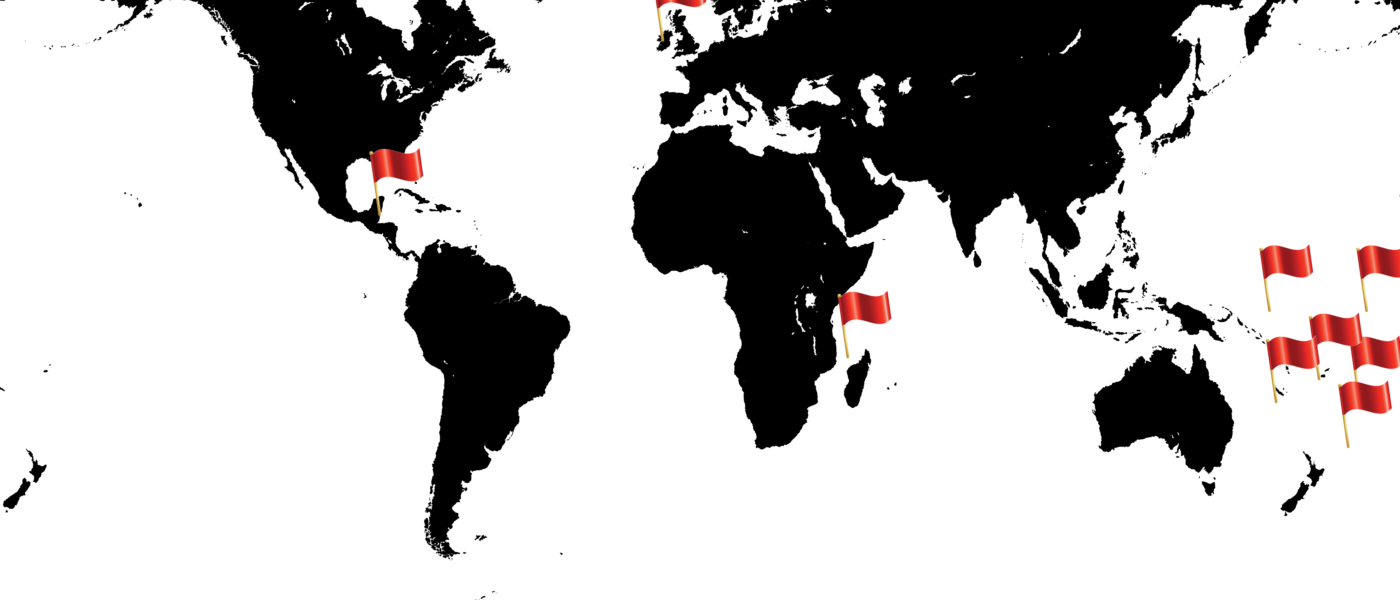

In the eighties and nineties, the citizenship by investment (CBI) industry was a veritable Wild West, with no real accountability or oversight. In the Pacific, many small nations emerged with citizenship by investment programs (

Tonga

Tonga’s program was first proposed by Thomas Chen, who would later become the Honoree Consul of Tonga in China, in the late 1970s. In 1982, Tonga’s king authorized the sale of passports to Hong Kong. It began issuing Tongan Protected Person Passports (TPPP), which conferred neither citizenship nor residence rights in the country, nor visa-free entry. Many countries questioned the authenticity of the document and refused entry to TPPP holders.

In 1988, the opposition party was able to force the repeal of the CBI Act but, strangely, passport sales continued in Hong Kong for years thereafter. In 1996 the king was able to sell an additional 7,000 passports to raise money, but that would be the end of that chapter. In 1999, Tonga

Marshall Islands

During this program’s obscure 10-year lifespan between 1987 and 1996, the Marshall Islands sold around 2,000 passports, mainly to Chinese applicants. Repeated pressure from the US government lead to the program’s closure in the mid nineties.

Although a mutual visa waiver agreement is in place between the US and the Marshall Islands, naturalized citizens of the latter cannot access the US without a visa. Like other similar schemes, the program was full of controversy and allegations of corruption. After the program’s termination, the Attorney General embarked on a campaign to cancel passports that had been illegally sold for under $100,000.

Many Chinese immigrated to the Marshall Islands during those years, which led to a great deal of racial tension in the country which, unfortunately, lasts to this day.

Nauru

The island of Nauru is famous for its economic roller-coaster ride from poor to rich and back to poor again. In the late seventies, Nauru had one of the highest GDPs per capita in the world, thanks to its substantial phosphate deposits. When the natural resources – and the sovereign wealth fund they had fed – diminished, the country’s economy was in a shambles. Nauru needed new ways of making a living.

In the nineties, Nauru tried to rebrand itself as an offshore banking center and started selling passports in 1998. It drew the ire of the inter-governmental Financial Action Task Force of Australia, and U.S. pressure grew tremendously in the wake of 9/11 when two suspected terrorists from the Turkestan Liberation Organization were caught holding Nauru passports.

In February 2003, authorities also discovered that two suspected al-Qaeda agents they had captured in Malaysia also held Nauru passports. While visiting Washington, D.C., in February 2003 for a medical procedure, then-Nauru president Bernard Dowiyogo signed an executive order terminating the passport sales and the offshore banking ventures, reportedly while under US pressure. He died ten days later.

Kiribati

In 1995, the small island of Kiribati introduced an “investor” passport program where an applicant would pay $15,000 and execute a promissory note of an additional $5,000. The recipient would receive an “investor passport” with the mark ‘INVESTOR’ or ‘N-KIRIBATI”. He or she would need to visit the Immigration Office every 12 months for renewal of the status. The program didn’t provide Kiribati citizenship but allowed the applicant to stay in Kiribati for five years, and was renewable. The program was repealed in 2004 following pressure from “donor countries”.

Tuvalu

Perhaps the most obscure of the lot, Tuvalu began selling passports in 1997 at $11,000 each or $22,000 for a family of four. Valid for five years, 3,000 passports were sold to mainly Chinese investors.

The Tuvalu CBI was also a passport-for-sale scheme rather than a naturalisation scheme, and didn’t confer citizenship. Many visa-free destinations would require a visa.

Belize Economic Citizenship

Following in the footsteps of St Kitts & Nevis, in 1985 Belize amended its citizenship act to include an “exceptional contribution clause”, but it was only in 1995 that Belize decided to structure that clause into a formal CIP. The program bestowed full citizenship minus the right to vote. The application fees amounted to US$10,000 for a single applicant and an additional $50,000 for a family of four.

Viewing also this CIP as a security threat following 9/11, the US pressured Belize into closing the program in 2002.

Ireland Citizenship by Investment

In 1984, Ireland introduced a

In closed government circles, controversy rocked the program in 1990 (but only became known to the public years later), as Minister for Justice

The highly irregular process, which involved Saudi and Pakistani nationals, took place following the recommendations of the Taoiseach (the Prime Minister of Ireland)

It was only in 1994 that this story

Comoros

The Comoros CIP came into law in 2001 in accordance with the African nation’s constitution, but regulation guiding the program only appeared in 2008. The purpose of the program was, originally, to get cash in return for granting citizenship to stateless people, known as Bidoon, in the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait.

From the beginning, there were irregularities, and a number of parliamentarians insisted the law was unconstitutional. A cross-party commission found that the law allowing the sale of citizenship was changed during a parliamentary session that violated its own procedures. The bill that was promulgated, said the commission, lacked the correct signatures and stamps and did not officially figure on a list of laws passed by the National Assembly.

Although originally meant as a solution to the Arab Peninsula’s Bidoon-conundrum, the government also sold passports to other foreigners. The first scheme, which ran from 2006 to 2011, was supposed to earn Comoros $200m in exchange for citizenship to 4,000 stateless families. After a brief suspension, the government

The commission estimated a shortfall of $100m from passports sales. Now, former presidents Ahmed Abdallah Mohamed Sambi and Ikililou Dhoinine stand accused of embezzlement of public funds. The current Comoros government suspended the CIP when coming to power in May, 2016.

Back from the grave

Most of these programs are long gone but some have been resurrected. The Vanuatu and Samoa CIPs took 20 years to return, both having made forays into the CBI world in the nineties. Vanuatu launched a series of CIPs, while Samoa launched a “fast-track” CIP after three years of residence at

After an unsuccessful dalliance with CBI between 2008 and 2010 that was riddled with the controversy that surrounded the naturalization of ousted Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, Montenegro’s CIP returned in 2018. Grenada’s program (1997–2001) also made a return in 2013 after more than a decade of suspension.

Stephane Tajick is a researcher in the field of investment migration, the developer of the STC database on more than 200 residence and citizenship by investment programs worldwide. He is a regular columnist at Investment Migration Insider.