The Bizarre Story of How the King of Tonga’s Court Jester Lost $26 Million Made From Passport Sales

This is the incredible tale of how a Hong Kong businessman persuaded the King of Tonga to sell $26 million worth of citizenships to Chinese investors, and how the King’s court jester lost it all by trading life-insurance policies for the terminally ill.

The original passport king

Citizenship by investment was not always a legitimate business. In the eighties and nineties, a variety of Pacific island nations sold thousands of citizenships by way of opaque methods, unburdened by regulatory oversight.

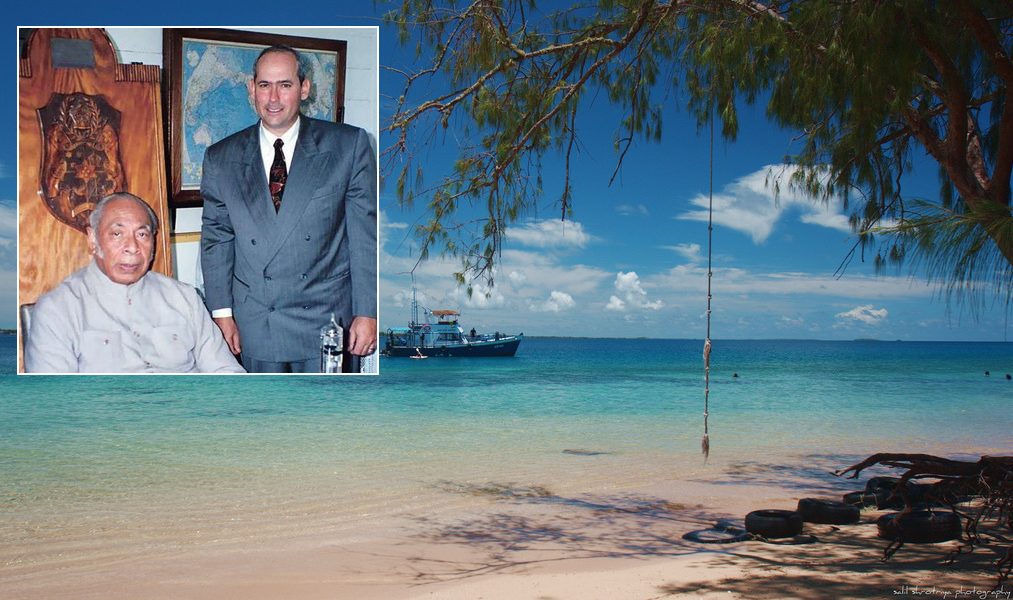

As far as we know, the first person to propose the exchange of citizenships for capital in the Pacific was Hong Kong entrepreneur George Chen, who would become the Honorary Consul of Tonga in China. In 1982, he persuaded the king of Tonga – Tāufaʻāhau Tupou the Fourth, who at the time was

The Pacific state began by issuing Tongan Protected Person Passports (TPPP), which conferred neither citizenship nor residence rights in the country, not even visa-free entry. Predictably, many countries questioned the authenticity of the “passport” and refused TPPP holders. The King realized that, in order to make money, he’d have to sell actual passports.

The sale of real Tongan citizenships commenced in earnest in 1983. Among the first customers were ousted Filipino Dictator Ferdinand Marcos, his wife Imelda of shoe-collection fame, and their children.

Throughout the eighties and nineties, the king, with the help of George Chen, sold in excess of 7,000 passports, raising some US$26 million. According to a New York Times article from 2001, Mr. Chen deposited the CBI-proceeds in an ordinary checking account at the San Francisco branch of Bank of America after the king had refused to let it remain in Tonga. If left with Tonga’s government, said the King, it would all be spent on roads.

The jest was yet to come

US-born Jesse Dean Bogdonoff had multifaceted career history. A Buddhist who had earned his MBA in night school, his CV included stints as a carpenter, dishwasher, musician, and trail guide, as well as well as a salesman of magnets that purportedly cured back pain. He would later take up work as a professional hypnotist.

By the mid-nineties, however, Bogdonoff worked as a securities salesman with the San Francisco branch of Bank of America. One day, he noticed that an ordinary checking account with an enormous balance had been left to languish for years, earning only a modest rate of interest. The money was the Tonga Trust Fund. Bogdonoff recognized an opportunity.

In 1994, according to the LA Times, Bogdonoff traveled to Tonga. On his third day there, a mutual acquaintance introduced him to the king, and the two reportedly hit it off immediately.

For the next five years, still working for Bank of America, Bogdonoff would manage the Tongan account from Tonga. he claims he helped the country earn nearly $10 million by moving some of the money out of the low-rent-bearing checking account and into higher-return asset classes like bonds.

But in 1999, disillusioned by a heavy workload and internal changes at Bank of America, Bogdonoff decided to leave the company. There was only one problem; he could not take the Tonga account with him without leaving himself open to a lawsuit from his previous employer. The only possible solution to that conundrum would be to, somehow, become an employee of the Kingdom.

And that’s exactly what Bogdonoff did.

He convinced the king to appoint him court jester. Bogdonoff himself explained it this way:

“I thought, You know, I am born on April Fools Day. And I have never been able to capitalize on that. I ought to become the Kings jester. I am a natural-born fool,” he said, according to a CNN article.

The royal decree to make Bogdonoff jester reads: “With my royal blessing may he go forth, ‘King of Jesters and Jester to the King,’ to fulfill his royal duty sharing mirthful wisdom and joy as a special goodwill ambassador to the world.” Like any court jester worth his salt, Bogdonoff regaled the king with flattering poetry and melodies played on a grand piano.

Not making the king laugh any more

That same year, the court jester received a promotion; the King appointed Bogdonoff financial advisor for the Tonga Trust Fund, a service for which he would receive a flat fee of $250,000 a year.

In an article from 2002, the Chicago Tribune explains what happened next:

According to the 27-page lawsuit against Bogdonoff and others, the Tonga Trust Fund followed Bogdonoff’s advice, putting the bulk of its money in what they were told were “perfect no-risk investments” that failed, and investing in companies the government later learned were paying Bogdonoff secret and “exorbitant” commissions for bringing in investors.

The fund invested $500,000 in FilmAxis.com, an international electronic film distribution company that ultimately filed for bankruptcy. And $4 million went to Trinity Flywheel Power, a startup company developing power storage systems and alternative energy devices that the lawsuit contends is “struggling to continue its existence,” and has stopped making owed payments to the trust.

The vast majority of the money, $20 million, went to Millennium Asset Management Services Inc., a company that purchased viaticals, the benefits of life insurance policies of people who were insured and believed to have little time left to live.

The Tonga Trust was to receive $26 million for its Millennium investment in less than two years, due on June 6, 2001. The money, the equivalent of more than half of the government’s annual revenues, has never appeared.

Tonga sued Bogdonoff and was eventually able to recover about $2 million of the funds but the scandal led to a national outrage that saw many heads roll. A number of ministers were forced to resign and a series of riots roiled the kingdom during the 2000s. In 2008, the aging king ceded most of his day-today powers, relinquishing his hold on the country, bringing democracy to Tonga.

Bogdonoff, no longer welcome in Tonga, eventually reached a settlement with the government which, according to himself, has made him a pauper. He agreed to pay Tonga US$100,000, a certain percentage of his income until 2014, 50% of any proceeds from future book or movie

Christian Henrik Nesheim is the founder and editor of Investment Migration Insider, the #1 magazine – online or offline – for residency and citizenship by investment. He is an internationally recognized expert, speaker, documentary producer, and writer on the subject of investment migration, whose work is cited in the Economist, Bloomberg, Fortune, Forbes, Newsweek, and Business Insider. Norwegian by birth, Christian has spent the last 16 years in the United States, China, Spain, and Portugal.