Tajick: Remembering the Dead Part 1 – Residence by Investment Programs of Yore

This is the first in a two-part series on now-defunct residence and citizenship by investment programs. This week, we look at

As we enter 2019, the investment migration industry is surfing confidently on a rising tide of both demand for and supply of residence and citizenship by investment (RCBI) programs. The bull market is now in its ninth year and there’s little to indicate any imminent reversal of the trend. Europe alone saw the number of golden visa programs grow from three to 23 over the last decade, and we haven’t had any closures since 2016 (Hungary).

But this unprecedented series of conquests was also accompanied by a handful of momentous instances of attrition; we lost some good ones along the way, like Canada’s Federal Investor Immigrant Programme, an exceedingly popular scheme for decades. The recent uncertainty about the UK Tier 1 investor program has had us holding our breath regarding the possible termination of one of the market’s real blue-chips. As it fights for survival, let us go down memory lane to recall some notable RCBI schemes that have fallen by the wayside along the road to our now $20 billion a year market.

The Hong Kong Capital Investment Entrant Scheme

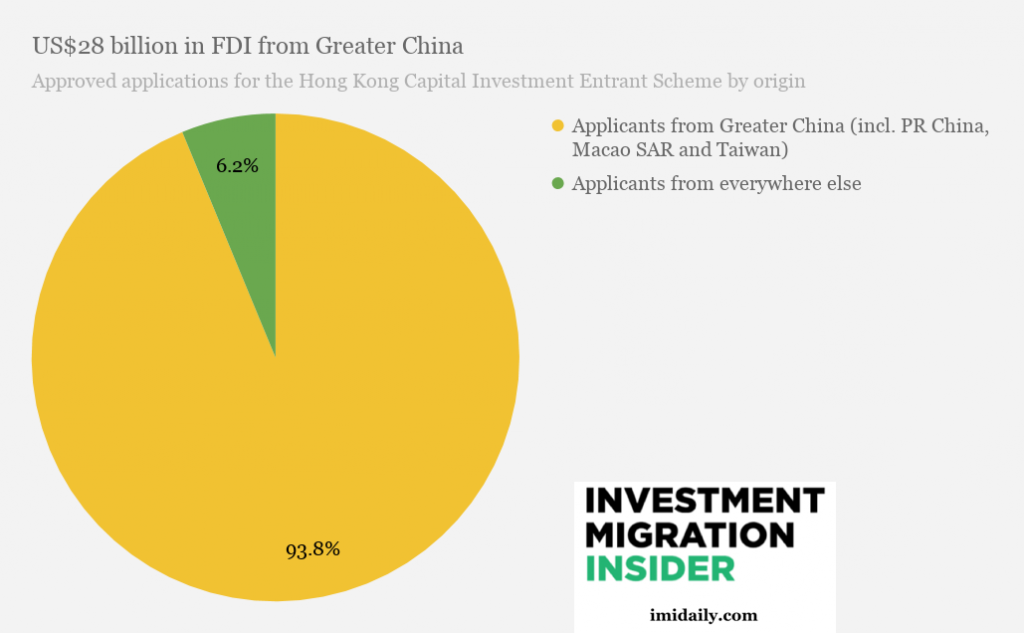

Launched in 2003 to help Hong Kong rebound from

Why Chinese nationals with

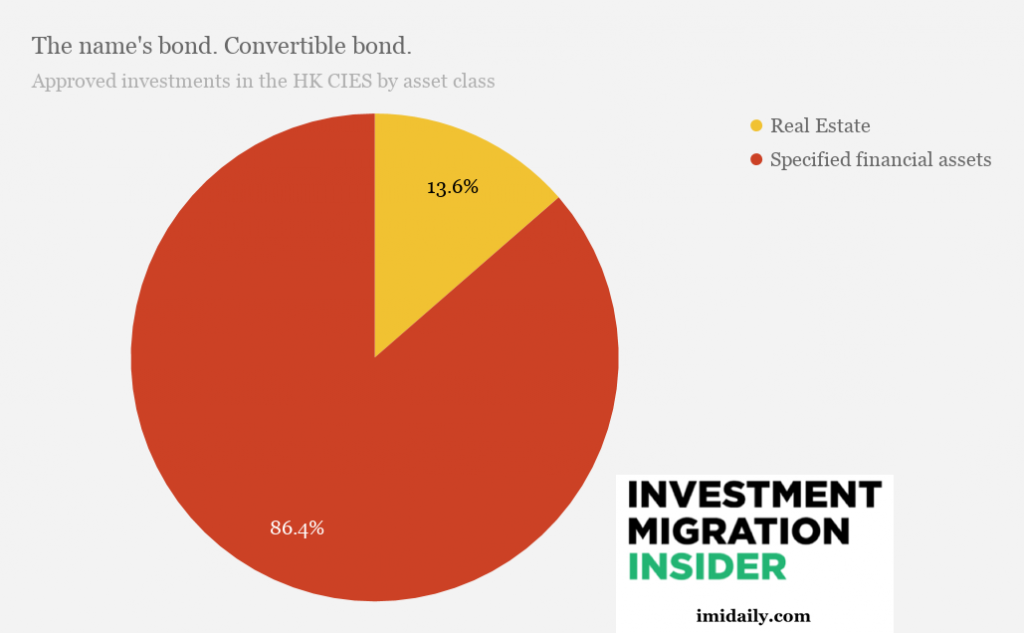

Once in possession of, say, an Ethiopian permanent residence card, the prospective CIES participant had to make a passive investment to the tune of HK$6.5m for seven years in order to qualify for permanent residence at the end of that term. In December 2010, that amount was adjusted upward to HK$10m.

As interest rates dropped, the CIES – which saw most of its qualifying investments come in the form of bank deposits and bonds – became less attractive for the city-state from an economic policy point of view and the program eventually closed in January 2015.

Canadian Immigrant Investor Program

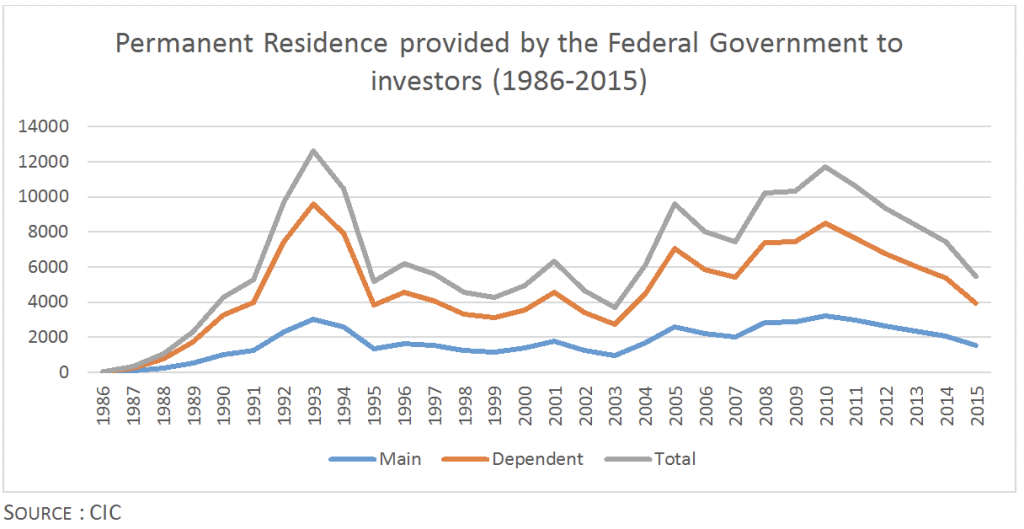

When first launched in 1986, the Canadian Immigrant Investor Program (CIIP) found itself in the shadow of the highly popular Immigrant Entrepreneur Program that regularly garnered thousands of applications from Hong Kong residents.

Initially, the Federal Government required that applicants demonstrate a net worth of at least CA$400,000 and that they invest at least half as much in Canada. The program reached its high water mark amid the Hong Kong emigration wave of the early nineties; over 12,000 individuals were admitted under the program in 1993.

Throughout the CIIP’s 30-year lifespan, Canada admitted about 200,000 individuals. That’s over 50,000 main applicants and billions worth of economic impact over three decades. Vancouver, for the total existence of the CIIP, welcomed more than half of all immigrant investors in the whole country.

In 1999, the program doubled in price to CA$

The Conservative government of the day decided to replace the program with the Immigrant Venture Capitalist Pilot Program, which was much more expensive, requiring a $CA2 million at-risk investment for 15 years. The program was a failure, partly due to the Quebec Immigrant Investor program’s continued existence at a price of CA$800,000 for five years and with exactly the same benefits.

Hungary National Economic Interest (AKA The Bond Residence Programme)

Launched in 2013, the Hungary RBI came under severe criticism in 2015 and 2016 from the opposition party due to Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s policy of closing the doors to paperless migrants from the Middle East and North Africa. The program’s existence was never really secure. On the last day of March 2017, the Hungarian government announced it was closing it down, citing as its reasons that Hungary didn’t have an economic need for the program following the improvement of the country’s credit rating.

Modeled on Quebec’s QIIP, the Hungarian Bond Programme had five chief intermediaries, approved by the Parliament’s Finance Committee to participate in the program. The intermediary would secure €300,000 from the foreign investor, invest €271,000 in state bonds, and pocket the difference.

Five years on, the investment was returned to the intermediary company, who in turn repayed the program investor. These five companies came under criticism for opaque practices and for having incorporated in jurisdictions viewed as tax havens. Estimates indicated they made roughly $90,000 on each application when adding service fees and interest earned on the bonds. Financing options were also introduced at $150,000, increasing the intermediaries profitability. The Hungarian government, on the other hand, announced a net loss of €16m from the program by 2017.

The program also came under scrutiny when a Russian applicant, convicted of tax fraud in Russia, received approval to the program after using his St Kitts & Nevis nationality to apply. The authorities only requested a police report from St Kitts & Nevis and none from Russia. Between 2013 and 2017, 6,585 third-country nationals and their 13,300 family members were granted permanent residence permits under the program. The overwhelming majority of investors came from China. During the same period, 5,432 Chinese citizens spent €1.6 billion to buy residency bonds for themselves and their families.

Back from the grave

Many

Further resurrections of bygone programs – adapted to the modern world of permanently

Stephane Tajick is a researcher in the field of investment migration, the developer of the STC database on more than 200 residence and citizenship by investment programs worldwide. He is a regular columnist at Investment Migration Insider.