Startup Visas: Governments Want Them, But Your Clients Don’t

The investment migration world has been abuzz over startup/entrepreneur visas in recent weeks:

- Jean-Francois Harvey said his firm was “phasing out of golden visas” to focus on startup visas (SUVs) instead because they, in his view, added more value to both his firm and the destination country, and is what governments are looking for. See: Harvey Law Takes Golden Visas Off Shelf, Turns Focus to Startup/Entrepreneur Programs

- Paul Girodo, in a recent opinion piece, indicated it’s just a question of time before SUVs replace golden visas across Europe: “By this time next year, according to the popular press, EU golden visa programs will have changed so much that they will have effectively ended.” See: Paul Girodo: Golden Visas May Be On Their Way Out – Here’s What Will Replace Them

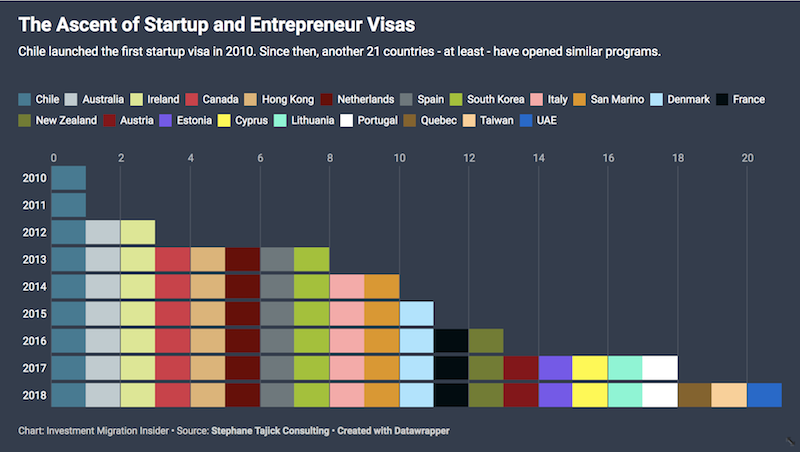

But startup visas are not a new phenomenon and, in fact, the trend has expanded rapidly since 2012. Following Chile’s introduction of an SUV in 2010, more than 20 such programs have emerged across the globe, and the concept looks set to make an appearance in virtually every advanced economy.

Since many in the industry are unacquainted with these programs, I’ll put it plainly; they are not what your clients are looking for. The reason we are speaking about them is that they are what Western governments want. Are startup visas really going to replace investor visas? Let’s dive in.

What’s motivating governments to open these programs?

My last two annual government reports devoted many pages to analyzing the emergence of startup visas as a phenomenon. Since the 2008 financial crisis, interest rates have remained low in Western countries. The hope was that cheap capital would help resuscitate their economies. It did – to a certain extent – but maintaining growth has been a constant battle. Most Western economies are at or near stagnation, with GDP growth between one and two percent, below what is considered to be a healthy rate of expansion.

In its quest for increased economic expansion, countries have employed increasingly creative methods to attract growth agents. Companies with potential for fast growth – primarily in tech sectors – became prime targets. Everyone dreams of bringing the next Google or Facebook to their shores. High-paying jobs, small footprints, rapid expansion; what’s not to like. Many European and North American jurisdictions created startup visas precisely with this end in mind. But has it worked?

How popular are startup visas?

Few governments publish precise statistics on their startup visa programs, but what we can glean from those that do is that, overall, this is not a popular immigration route. The 22 startup visa programs currently in operation yielded an estimated 1,500 approved applications in 2018, 240 of which in Canada alone.

Those are not numbers to get excited about. A handful of these startup programs also face domestic competition from other entrepreneur schemes within the same country. The available statistics rarely provide useful information on the country of origin, investment raised, success rate, or even their economic impact. We are still very much in the dark about the viability of such routes.

Are startup visa the future of the industry?

The short answer is ‘no’. The long answer is that, due their customized process, multi-step, multi-year process, these programs may be well-suited to a full-service law firm like Harvey’s, but they make little sense to your average RCBI-consultancy. At least not in their current form.

Ask any large investment migration firm, and very few of them will indicate an interest in the circuitous process of an entrepreneur program because that isn’t scalable. What most firms in our industry want to spend their time doing is helping clients through an easy, simple, replicable process hundreds of times a year. The last thing they want is to have to evaluate a startup company project and its viability, something they probably don’t have the expertise for.

More importantly, startups are rarely cash-rich. They are unlikely to dish-out tens of thousands for professional services. The reality is that the current format of most startup visas makes them unattractive for the investment migration industry. The application volume (demand) is too low, and each client represents low-margin, complicated work.

The hybrid model that could work

The crux of the startup visa problem is a very ordinary conflict of interest: Politicians want innovative, fast-growing startups to boost their economies, and don’t want foreign-owned empty apartments that drive up the price of housing for their voters. Meanwhile, international HNWIs want a simple, passive investment that gives them residence permits but don’t want additional fuss like physical residence requirements or hands-on involvement in a business.

Is there a way both governments and investors could have what they want?

Yes, there is.

All you need to do is to match foreign capital with local startups. HNWIs get to passively invest in an asset class and obtain a residence permit; Local economies get the growth they want by having at their disposal a pool of other people’s money to fund new ventures.

There are several examples of how to execute this model:

- The US EB-5 program attracts capital from foreign investors who accept that their money will be at risk

- Australia makes residence by investment applicants risk capital in a layered investment portfolio that includes low-, medium-, and high-risk assets.

France, New Zealand, and the Netherlands spring to mind as countries where this model would be viable.

Finding capital is a lot easier than finding startup founders who actually have a clue. Explaining the application process and investment requirements to a client is a lot easier than evaluating the business model of a tech-startup.

What the EB-5 program has taught us is that matching immigrant investor capital with local entrepreneurship is feasible. But startup projects are much riskier than most EB-5 regional center projects.

Startup visas are far from efficient in any of the existing formats. They attract too few applicants and, to the best of my knowledge, have yet to produce any unicorns.

The Australian SIV and the US EB-5 demonstrate that investors are willing to risk a great deal of money if it gets them a residence permit. Canadian 5-year, zero-interest investor programs, likewise, prove that immigrant investors are quite happy to forego hundreds of thousands in interest payments they otherwise would have accrued, as long as their kids can attend McGill.

Properly designed and executed, there are program models that can put immigrant investor capital to good use, and most of the unpopular side-effects (like higher home prices) can easily be avoided.

Unfortunately, the EU Parliament, by voting in favor of phasing out RCBI programs is on track to throw the baby out with the bath-water. It’s the lack of imagination and vision that, regrettably, plagues the public sector. For years I have had the unfortunate chance to witness government wasting the untapped potential of immigrant investor programs and the incredible economic impact they could have. This is especially the case in Europe, where the resentment against anybody with money has always been strong.

The future economy is one looking to constantly optimize the free travel of capital, talent, and good ideas. In that future, investors and innovators go hand in hand. They just aren’t necessarily the same people.

Stephane Tajick is a researcher in the field of investment migration, the developer of the STC database on more than 200 residence and citizenship by investment programs worldwide. He is a regular columnist at Investment Migration Insider.