Diseconomies of Scale in the Investment Migration Market: Why IM Remains a “Boutique” Industry

Tens of billions of dollars move through the investment migration (IM) market each year. More than a hundred thousand professionals are involved in the industry directly; orders of magnitude more take part indirectly. Why, then, are there no gargantuan IM corporations?

The short answer is that in the IM field, economies of scale are limited. To understand why that is the case, we must first understand the type of market conditions that are conducive to economies of scale.

But first: What are economies of scale, exactly? They are simply the economic benefits companies can derive from being larger. Though size may be an advantage for several reasons, here are three common examples, and how they match conditions in IM.

Cost economies of scale

From time to time, when I visit my hometown in Norway and I’m out driving with my father through a residential neighborhood, he’ll point to some small café, or pharmacy, or empty storefront window and say “when I was your age, that place used to be a grocery store.”

Back in the 1970s, my hometown had a small, independent grocery store every few hundred meters or so. Today, practically none of them are left.

What happened?

Quite simply, a handful of enterprising grocery store owners began buying out their competitors to start grocery chains that could order supplies in bulk. Buying larger quantities meant they could demand much lower prices from their suppliers, savings they could pass on to consumers. It also enabled them to stock a wider range of goods. Consumers liked the lower prices and the broader selection of the supermarkets. Within the space of a generation, Norway went from having a small, independent grocery store every two blocks to having a big, chain-store supermarket every 20 blocks. Today, nine in ten Norwegians get their groceries from just a handful of billion-dollar supermarket chains.

It’s the same story in every developed country, and it’s perfectly natural. In the groceries market, the advantages to scale are plentiful. It’s the reason Walmart is such a successful company.

Does this apply to IM?

Can IM companies get better rates from their suppliers (local agents in CBI countries, for example) and pass those on to their clients? Yes, IM firms that submit high volumes of applications to a particular program can and do get better rates from their local partners but they don’t always pass the savings on to the consumer. Even if they did pass the processing cost savings on to the consumer, it wouldn’t make much of a difference in the total cost for the investor. Sure, the IM firm could reduce its client fee, but it could do nothing about the principal investment/donation amount stipulated by the IM program itself, which accounts for the lion’s share of the investor’s total outlay.

In other lines of business, economies of scale originate not from natural market dynamics as described above but, rather, from government policies that incentivize (or necessitate) scale:

Regulatory economies of scale

Why do we have the Big Four accounting firms?

Until the 1980s, they were the Big Eight. In 1989, they became the Big Six, then the Big Five in 1998. Finally, when Enron collapsed and took Arthur Andersen with it, the Big Four remained. By 2011, they accounted for 99% of audits among FTSE 100 companies.

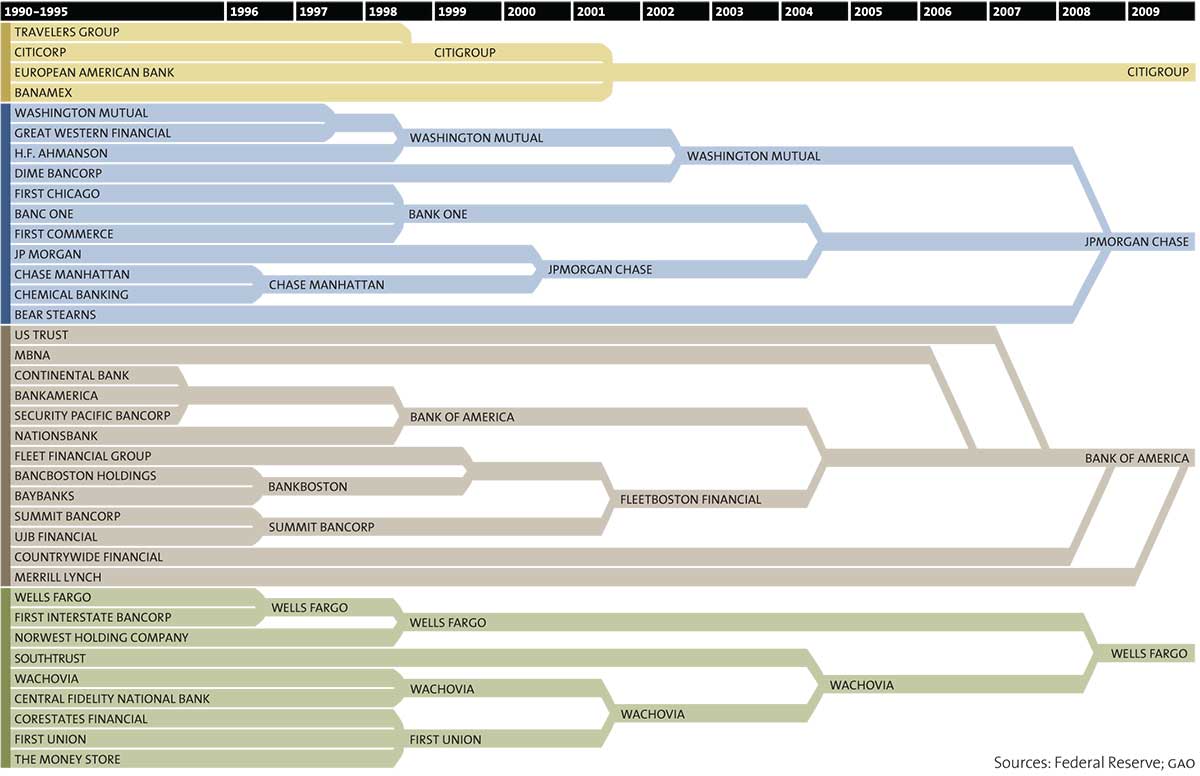

Something similar has happened in the world of banking. By 2016, the “Big Four” American banks held nearly half of all US bank deposits.

What kinds of economies of scale drove this consolidation? It’s not like KPMG gets cheaper MBA graduates by hiring them in bulk and then passes those savings on to the firms it advises.

Both banking and accounting are heavily regulated lines of work. Regulated industries need things like certificates, licenses, legal expenses insurance, in-house legal counsel, and compliance departments. The more regulations, the bigger the compliance department needs to be. And the bigger the compliance department needs to be, the bigger your firm needs to be to justify the expense.

Big firms can afford to comply. Small firms can’t. Incidentally, that’s one reason it’s typically the largest firms in any particular industry that advocate for more regulations. They’ll gladly offer to help write those very regulations – this is known as regulatory capture – because they know they’ll be able to afford compliance, while their upstart competitors won’t. This happens in IM too.

I’m not saying that accounting and banking firms consolidate only – or even mostly – for regulatory advantages. But, certainly, the relatively light regulation of investment migration is one of the reasons there are no “Big Four” investment migration companies. If we did have more regulation of IM, consolidation would be an inevitable consequence, and we’d see fewer, bigger firms.

Prior to November 2018, when the Chinese IM market was strictly regulated and required licenses, the world’s largest IM firms were all in China. Some had more than 1,000 employees and several thousand clients a year. Licenses were hard to come by so, if your firm had one, there were plenty of IM professionals willing to work for you. But when the government deregulated that market, the huge Chinese firms immediately started disintegrating. Now that almost anyone could provide IM advisory services, many key employees left to start their own, boutique (a more flattering word for “small”) advisory businesses.

Capital intensity-related economies of scale

Sometimes, the capital requirements of your business downright require scale. This is true when the initial investment amounts are extreme. To build a nuclear power plant, for instance, you’ll need to invest billions of dollars upfront, years before you see any return. Some ordinary guy with entrepreneurial ambitions straight out of school can’t just decide one day that he’s going to start a nuclear power company.

But he can just decide one day that he’s going to start an investment migration firm. He won’t need billions of dollars. Just a laptop.

The diseconomies of scale in investment migration

Among the three types of economies of scale discussed above, neither is present in investment migration.

- Scale can only help so much in reducing costs;

- Regulations are minimal, so compliance isn’t prohibitively expensive;

- Starting and running an IM firm doesn’t require much capital.

Because investing in a second citizenship or residence permit can be an intimate, life-changing affair, clients like to know their advisors personally and build a relationship of trust. They, therefore, don’t mind that the firm is “boutique”. In fact, many prefer it. They may not want to buy citizenship from an algorithm or a faceless corporate behemoth. That’s one reason most IM firms have fewer than 10 employees.

Another disadvantage to scale in investment migration is the organizational slack that results from having offices in geographically, culturally, and linguistically distant branches. You can’t necessarily expect the teams in Lisbon and Capetown to be on the same page. They might both be working on a similar project or report, or they may both be targeting the same group of clients without the other knowing about it. They may have bloated expense accounts. The assistants could have assistants, for all you know from where you’re sitting in the head office on another continent.

Because you need very little in terms of compliance or capital to start an IM advisory business, employees at multinational IM firms are wont to leave their jobs and start their own, competing businesses offering the same services if they sense their contribution isn’t proportionally rewarded. This pattern of employees learning the RCBI ropes in an established company only to go their own way after having learned the necessary skills and forged the right connections is the bane of IM firms from Dubai to Dalian (and the source of not a few lingering grudges).

Even the IM firms we think of as having large scale, the international ones with hundreds of employees, are often just loosely affiliated networks nominally operating under a single banner. Because local conditions (and expertise) make it impossible to take the same market approach in different countries, the devolution of authority to local offices is inevitable. Your firm might be headquartered in London, but your Managing Partner in the Beirut office – half a world away – will have his own way of doing business, his own institutional network, and a different recollection than you of “who really built this office.”

IM history is replete with local branch managers who quit, convinced all that branch’s essential employees to join in starting a competing company, leaving the old firm gutted. Sometimes, they don’t even bother changing offices.

Christian Henrik Nesheim is the founder and editor of Investment Migration Insider, the #1 magazine – online or offline – for residency and citizenship by investment. He is an internationally recognized expert, speaker, documentary producer, and writer on the subject of investment migration, whose work is cited in the Economist, Bloomberg, Fortune, Forbes, Newsweek, and Business Insider. Norwegian by birth, Christian has spent the last 16 years in the United States, China, Spain, and Portugal.