Should Countries That Sell Citizenship Disclose Their National Debt to The Buyer?

We are living in exceptional times; debt burdens are high and the need for revenue is dire. Citizenship by Investment (CBI) laws allow the sale of citizenship without substantial naturalization periods, a contested – but overall effective – way to address sovereign financial predicaments.

Yet, CBI is itself but one aspect of the broader concept of citizenship. Citizenship comes with multiple overlapping – and at times deeply conflicting – dimensions that are likely irreconcilable.

The national debt burden, for example, which is borne by the public, is one such potentially irreconcilable dimension. If you are a citizen, you are part of “the public” and, consequently, partly responsible for paying back the public’s debt. Debt may be incurred individually, as well as in the name of a body politic. High levels of such public debt may lead to debt crises.

Careful what club you join

The matter of debt applies, of course, to all nations. What is of particular concern are the bail-outs of some creditors and private debt becoming public over time, being repayable through existing or novel regimes of taxation imposed. Likewise, bail-ins are measures where the end, a nationally sound economy, seems to justify the means at the expense of the individual investor. Although the circumstances may differ, the 2013 Cypriot deposit haircuts come to mind.

National debt refers to the total amount the government has borrowed over time (and not yet repaid). The national debt is usually measured as a percentage of the gross domestic product, the ‘debt to GDP ratio’. Such sovereign debt may find its expression as per-capita-debt, at least somewhat indirectly impacting or becoming assigned to citizens. Both national debt and government deficits may impact or even prevent private investment, adversely affect interest rates, capital structure, exports, as well as unfairly disadvantage future generations through higher taxes and inflation.

In the CBI bargain, one would surely hope that the overall economic viability of the selling state is sound and not ‘defunct by debt’ from the beginning of the engagement. When entering into any such pre-existing, shared (and not necessarily sustainble) debt, the risk for indeterminate outcomes may materialise in economic as well as political instability at some time in the future. As the contracts for citizenships include aspects or remnants of a social contract, realistically, all possible consequences of such an important decision should be considered.

The potential for asymmetric social contracts

Any undisclosed substantial national debt accrued before the purchase, especially vis-à-vis non-sophisticated parties in the passport bargain, may become an issue of fairness in the law of contract.

At the time of contracting, bargaining inequality may apply as to essential information pertaining to the sale of citizenship. Matters should not be assumed unless they are clearly understood in the terms and conditions in the contract for a new passport. In other words, do heightened requirements as to disclosure apply to membership bargains? Should the national debt, together with other important information, perhaps become a mandatory factor of disclosure by the selling state, akin to due diligence processes imposed on the purchaser?

Investor citizens may, in some circumstances, appear to fall short of ‘full’ citizenship status when it comes to the publishing of personal details on a register, the requirement to maintain an investment, or when facing limitations as to the active engagement in political office or, passively, in regards to voting.

On the other hand, CBI purchasers will likely be viewed as full citizens when it comes to a citizenry’s shared obligations, becoming committed from the juridical second of the purchase. This may include the factor of common debt. It is highly unlikely that the citizenship purchaser has, with their initial substantial payment, paid off all (including future) obligations or been insulated from a change in further revenue needs through taxation or otherwise.

Individual freedom from debt, however incurred, may in certain circumstances become a pre-condition for global mobility because states are able to prevent personal travel until the individual debt to the polity is paid off.

CBI strategies should thus not merely concern themselves with the ease of entry through the key of an investment as payment, but also with the personal socio-economic investment in the polity and its mid- and long term viability, as well as with the existing and changing rules pertaining to exiting a polity.

Do your homework

Pre-contract research into the financial foundations of a country offering instantaneous CBI naturalization is crucial, as there will be no time to find out about cracks, silent wealth confiscations, or impending economic collapse through years of residence. Ordinary substantive naturalization periods, much like engagement periods before the actual marriage that allow a prospective husband or wife to learn something of their partners’ debts, would allow the migrant time for research to ascertain whether the polity of choice is actually the one so desired. In the extremely short or even non-existent/waived periods of naturalization under CBI, this time of acclimatization no longer exists.

With the looming COVID19 global debt, worldwide interconnectedness of financial architectures, and the difficulty of effectively insulating any country from crisis, it has likewise become increasingly difficult to viably question RCBI as a sovereign practice.

CBI purchasers may greatly contribute to the prosperity of a polity. The positive mirror image of sovereign debt is “sovereign equity”. Christian Kalin, who coined that term, correctly points out that investment migration is an important tool to enhance sovereign equity and general financial independence of states.

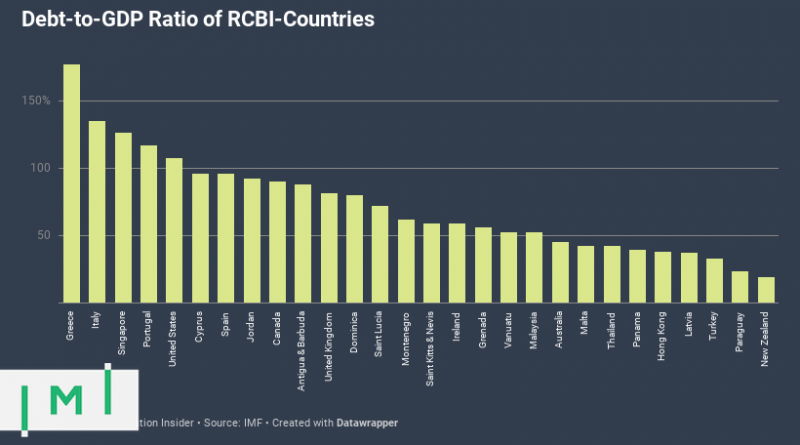

The takeaway is that research on a CBI-jurisdiction’s debt-levels – and, by extension, economic prospects – should be a critical part of the program selection process, lest the buyer unwittingly take on massive future liabilities.

Michael B. Krakat is a lecturer and coordinator for comparative Public law – International, Constitutional and Administrative Law – at the University of the South Pacific at Vanuatu and Fiji campuses. Michael is also a researcher at Bond University – Queensland – and Solicitor at the Queensland Supreme- and the High Court of Australia. He also is an academic member of the Investment Migration Council. He can be contacted at michael.krakat@usp.ac.fj.