Future of the Citizenship-by-Investment Market: Predictions for 2027

While a decade ago, citizenship-by-investment programs were a fringe interest, entered into only by a handful of avant-garde and adventurous investors, the last few years have seen the industry enter mainstream consciousness and blossom at a rate few could have imagined. Thousands of applicants, with the help of hundreds of companies, now go through a CIP every year.

But what will happen in the next decade? Will the trend continue its upward trajectory, or will we see CIPs closing down? Which factors would catalyze growth and which could hamper it? What type of changes can we expect in terms of program quality and pricing, and where might we see new programs emerge?

In the paragraphs that follow, I’ve laid out my arguments for why I feel confident the industry will continue to thrive. The reader is welcome to leave counterarguments (of substance) in the comments section.

The citizenship market

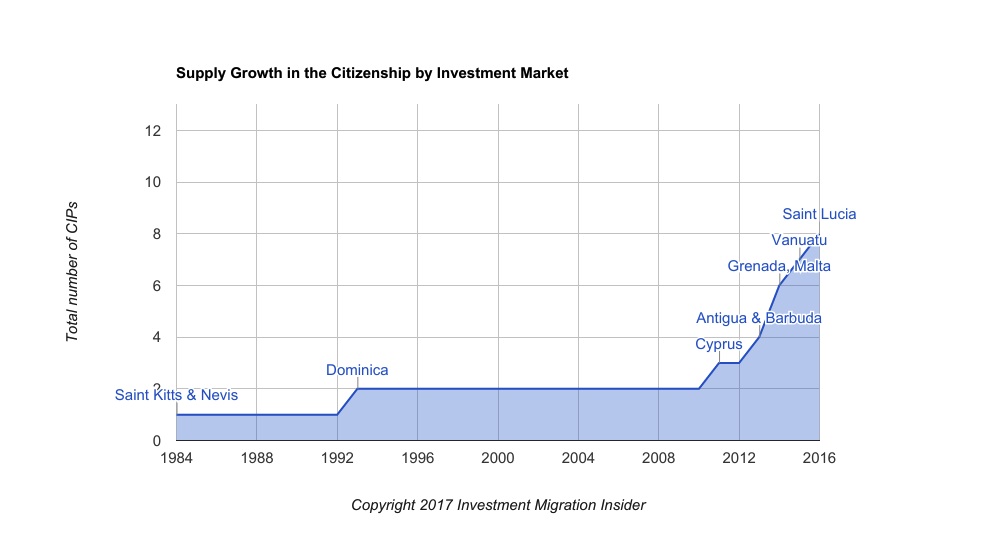

The Saint Kitts and Nevis Citizenship by Investment Program was, for decades, the only formal citizenship by investment program, the first mover. In the late 2000’s, however, a host of other Caribbean nations entered the fray and thereby created, for the first time in history, a market for citizenships.

There’s no use denying or sugarcoating it: passports are for sale. A passport is a commodity. While I know many will take umbrage to such a sacrilegious claim and my vulgar reduction of nationality to a mere economic good, the fact remains that citizenships are now subject to the same market forces that haunt washing machine manufacturers and elevator repairmen: supply and demand.

In the last decade, both the D and S curves of the passport-market have shifted markedly upward: Succeeding waves of well-heeled investors from emerging economies have cascaded onto the shores of an increasing number of FDI-hungry island nations. The market has grown by orders of magnitude and matured considerably.

But what will the CIP market look like ten years hence? It can only grow, shrink or remain the same. In my assessment, growth is highly likely, a reduction much less so, and a continuation of the status quo well nigh inconceivable because markets with this many participants are always in flux.

Let’s look at which factors could spur growth and which could hamper it.

Factors that could put the kibosh on the CIP market

In the seventies and eighties, many OECD states set about capturing the wealth of its most productive citizens by making them pay ever greater shares of their income in taxes and confiscating inheritances. These states wanted to squeeze blood from stones with impunity, and they would have got away with it too had it not been for those pesky little offshore jurisdictions that started to offer next-to-nothing tax rates, unnamed accounts and two-day company formation.

States in Europe and North America persist in their attempts to “harmonize” tax rates around the world (i.e. pressuring smaller, poorer countries to raise their shakedown standards), but the likes of Cayman Islands, UAE and Gibraltar just keep cramping their style! How are first-world politicians supposed to get rich people to fork over 75% of their income when they can easily escape to a tax-friendly jurisdiction?

Now that these jurisdictions offer citizenship and residence permits too, and Western governments are strapped for cash like they haven’t been in generations, finding a way to plug this capital leak (productive people going John Galt) has become an even more pressing issue for European and North American politicians.

These powerful state actors have a variety of deterrents they can deploy to thwart the development of the CIP industry. They default to hints of nefarious dealings, graduate to subtle pressure and vilification, escalate to explicit threats and, if all else fails to dissuade tiny island states to harmonize, impose tangible sanctions.

For an example of how to employ the vilification tactic, see how the shameless leftist manipulators venerable investigative journalists of CBS’s 60 Minutes recently cast aspersions on the CIP industry with no basis in reality. From “A rogues gallery of states” and “possible threat to national security” they lead the witness with loaded phrases that nonetheless left them with plausible deniability should anyone come asking for evidence.

Then there are the insidious, thinly veiled threats, which may include officials making public statements such as: “I think the European Commission needs to look more closely into passports-for-sale schemes to determine whether it could affect the visa-free arrangements X country has with Schengen”. OECD countries could also threaten, more directly, to put the country on a “blacklist” or to revoke visa-privileges.

External pressure from foreign governments, of course, is not the only menace to CIPs. Domestically, the electorate itself has the power to do away with such programs, but only if it genuinely wants to. I don’t think it does at the moment because, so far, the only victim of CIPs is the perceived sanctity of citizenship. For any real opposition to materialize, people must have a meaningful economic incentive, and I can’t see that one exists.

You could argue that cartelization and price fixing among existing CIPs, particularly in the Caribbean, could limit the growth of the industry. But cartels collapse the moment one member breaks ranks so, even if this should occur in the first place, I see it as unlikely to go on for any significant period.

The only substantial threat to the CIP market, therefore, is supranational bodies and the governments of high-tax rich countries, chiefly OECD, the EU and the US. Below, I explain why I think such opposition is surmountable.

Why the CIP market will continue to prosper

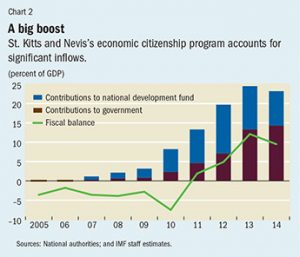

Governments – everywhere and without exception – are loath to relinquish steady streams of income, particularly when they were always available to their predecessors. I don’t know much about Maltese politics, but I’m confident the MIIP will persevere regardless of whether Labor or the Nationalists are in power. Despite each party’s eagerness to weaponize the program as a means of rebuking the other whenever in opposition, no president of a country with a GDP of US$10 billion wants to give up nearly a billion a year in FDI. MIIP funds are a mainstay of the Maltese Treasury, money the government can use to make sure nobody forgets their munificence come election day, and also boosts the GDP figures that give incumbent administrations bragging rights.

The self-interest of some governments, in other words, is a bulwark against pressure from other governments. While to Francois Hollande it would be nice if there were no CIPs inultra-low tax jurisdictions so that he didn’t have to hemorrhage thousands of millionaires a year, toGaston Brown of Antigua, it would mean slashing nearly half his budget, a feat not voluntarily stomached by a politician since, perhaps, Maggie Thatcher. The PM of France may have some to gain, but the PM of Antigua has everything to lose, and that’s why the ABCIP isn’t going anywhere.

In any market, introducing competition generally has the dual effect of lowering prices and improving quality. Saint Lucia, a new entrant, wisely made its first foray count in 2016 by offering the lowest investment requirements (lower price) in the Caribbean and a 60-day processing guarantee (higher quality).

Since the Caribbean programs grant more or less the same benefits, these passports are what economists refer to as “substitute goods” with low price elasticity, and it was therefore to nobody’s surprise that Saint Lucia’s aggressive entry strategy allowed the program to claim considerable market share right off the bat. They undercut the competition and lowered the bar, so if Barbados decides to launch a CIP tomorrow, they’ll have to either offer much quicker and simpler processing and/or start at around US$100,000 for a single applicant.

Claims to the contrary notwithstanding, you can put a price on citizenship, and that price keeps going down. Lower prices, ceteris paribus, will increase demand. The growing demand, in turn, will lead to longer processing times and possibly additional fees (such as the recently introduced Saint Kitts fast-track processing fee), raising margins for market incumbents. The higher margins and easily bested processing times will give rise to new CIPs, each time with lower prices and quicker throughput (at least until their CIU becomes sclerotic, as they all seem to do given enough time).

If it expects to grab market share, each new program must, in some respect or other, be superior to existing ones, either by offering lower prices or a better product. This downward spiral in pricing and processing time in the market will continue until margins are so trifling that entering it isn’t worth the trouble of designing and implementing a CIP. But there’s still plenty of room to reduce margins before that happens.

What’s more, in contrast to a decade ago, the industry now encompasses hundreds of companies and thousands of professionals, all of whom have a vested interest in the flourishing of the industry.

The CIP market in 2027

Since I’ve made a case for why I think the CIP market will continue to grow, let’s consider where the next generation of citizenship programs is likely to surface.

Not all countries qualify for a program; far from it. As in all markets, there are barriers to entry, and a jurisdiction must meet certain prerequisites even to consider itself a candidate. Chief among them is visa-free access to Schengen, a sine qua non for a CIP.

Among the good-to-have-but-not-strictly-necessary conditions are a common law legal system, English as an official language, political stability, low taxes and an economy small enough for a CIP to have a meaningful impact.

A slew of Caribbean nations fit the bill; is there any reason Saint Vincent & the Grenadines, Trinidad & Tobago, Bahamas or Barbados can’t have CIPs? There are thirteen CARICOM member states, most of which would qualify for a CIP.

What about Europe? Although nothing tangible has emerged as yet, there are murmurs that a Montenegrin CIP is afoot, with several companies vying for the concession. While accession talks are underway, Montenegro is not as yet an EU-member but does have visa-free access to Schengen (and Russia). If Montenegro can have a CIP, why can’t the other Balkan non-EU member countries, such as Serbia, Bosnia, Albania and Macedonia? They all have visa-free travel to Schengen, and they all could sure use the cash.

Then, of course, there are several Pacific island nations that, by dint of the shared history of British colonization, have rights and privileges analogous to those of the Caribbean islands. Vanuatu already runs a CIP very similar to those of its Caribbean cousins, and I see no reason why Micronesia and Kiribati can’t do the same.

But what about a program in an EU-member country, the gold standard of CIPs? The Baltic states are all in the union, have stable political environments and healthy economies. Crucially, though, they’re all small enough for a CIP to make a dent in the economy. Within the EU, the Maltese-Cypriot duopoly enjoys outsized margins. What’s stopping Estonia from offering EU citizenship in three months for 25% less than Malta?

All told, there are at least three dozen states around the world who could easily open a CIP, and many more who could do so if offering it at a discount.

I’ll go on record with a prognostication: By 2027, we’ll see two or three more CIPs in the Caribbean, one in the Pacific, two in the Balkans and at least one more among the EU-countries (if, indeed, that ramshackle union is itself still standing a decade from now).

I further predict that prices – across the board but particularly in the EU where margins are high – will continue to fall in lockstep with the proliferation of programs, that requirements and procedures will become simpler and that processing times will shorten.

Bureaucrats, particularly of the treasury and finance ministry kind, will continue to “express concerns” about the integrity of CIPs and vaguely threatening “negative consequences”. Nobody will listen.

Christian Henrik Nesheim

Editor, Investment Migration Insider

Christian Henrik Nesheim is the founder and editor of Investment Migration Insider, the #1 magazine – online or offline – for residency and citizenship by investment. He is an internationally recognized expert, speaker, documentary producer, and writer on the subject of investment migration, whose work is cited in the Economist, Bloomberg, Fortune, Forbes, Newsweek, and Business Insider. Norwegian by birth, Christian has spent the last 16 years in the United States, China, Spain, and Portugal.