China’s Millennials: What Does the World’s Largest Investor Migrant Group Want? Part 3

Mr. Lu’s Tea Leaves

With Luc Lu

A seasoned veteran of the Chinese RCBI industry keeps readers abreast of overarching trends in the world’s biggest investment migration market.

This is the third installment of a three-part series on China’s millennial generation and how it is shaping the world’s largest investment migration market. Read Part I here and Part II here.

As we enter the 2020s, even the youngest of those born in the 1980s are in their thirties. In China, this generation is quickly becoming the main driver of the country’s investment migration market. Millennials, here defined as those born between 1980 and 1996 account for about 23% of the overall population. Due to the rapid economic transformation of the country in the years since they were born, China’s millennials are very different, both from their parents and their children (who are just now being born).

Compared to their parents, millennials want very different things from life, work, and – the focus of this discussion – immigration. What worked with Generation X won’t work with Generation Y. This article will contrast millennials with the generations that came before and illustrate how that will change the shape of Chinese investment migration.

Sea turtles, seaweed, and seagulls

A peculiarity of the Chinese language is the abundance of homonyms available to those fond of puns and euphemisms. Sometimes, these are used for practical reasons, such as when referring to topics considered “sensitive” on Chinese social media platforms and wanting to avoid censorship. Other times, they are used simply because the two homonyms are not only phonetically similar but also apt metaphors.

A prominent example of this is the term Sea Turtle (海龟, pronounced “haigui”), which is pronounced in exactly the same way as 海归, the short version of a longer term that in Chinese popular culture has come to denote compatriots educated abroad who have since returned to their native China. The metaphor is a reference to certain species of sea turtles that, after spending their lives roaming the seven seas, famously and inexplicably find their way home to live out their days on the same beach where they once hatched.

A related pair of metaphoric homonyms is seaweed (海带, pronounced “haidai”) and 海待 (also “haidai”), another pop-culture word that refers to Chinese students who, having completed their overseas education, return to China but can’t find jobs because they are not all that competent.

While sea turtles have a long and vaunted history in China (at least three major foreign education fads have taken place in modern Chinese history), their millennial cohort is a product of erstwhile leader Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening Up period. In acknowledgment of the skills-and-technology gap between 1970s China and the West, the famously pragmatic Deng – who had himself spent years working and studying in France in the 1920s – publicly endorsed the notion of sending Chinese students abroad. “It’s one of the most effective ways of comprehensively enhancing and strengthening the economy within five years,” he commented in response to a Tsinghua University report on the subject in 1979. “We ought to send them in the tens of thousands, and not in the dozens like we do now.”

The Chairman’s remarks set off the third wave of Chinese going abroad for their rich-world schooling. Where the first and second waves had been state-financed, the third was self-funded. This was Deng’s China, after all, and state-subsidies – of all kinds – were going out of style.

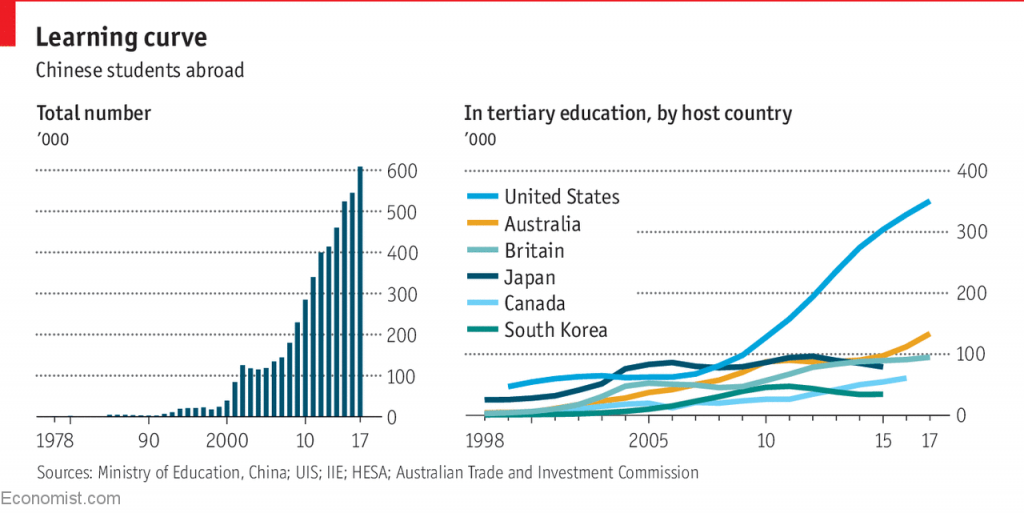

In 1980, Beijing formally permitted self-funded overseas study and Chinese attendees at American universities began growing at exponential rates virtually overnight. But being allowed to study abroad isn’t the same as affording it; despite the geometric rates at which the numbers were rising, their spurt had started from a very low base and they never number more than a few thousand a year throughout the 1980s.

The sea turtles that began returning in the ’90s, therefore, were in a privileged position; an admired group still low in numbers and awash in job offers. The economy, hamfistedly managed during the planned economy years, was in earnest beginning to bear the fruits of Deng’s acclaimed doctrine: “To get rich is glorious.”

By the turn of the millennium, some 40,000 Chinese studied abroad. By 2017, their numbers had swelled beyond 600,000. The sea turtles, at this point, were no longer such a rare breed and, in the job market, by no means considered special. When more than half a million sea turtles came home in 2018 alone, they found their native shore already crowded. Today, China is home to more than six million sea turtles.

Many of them have found their homecoming a disenchanting experience. Those who stayed behind lament the sea turtles’ frequent failure to re-adapt to Chinese cultural mores and ways of thinking. Employers often characterize them as excellent on paper but, in practice, unremarkable and even incompetent.

Nonetheless, a not insignificant proportion of sea turtles – particularly the millennial ones – really did benefit from their international experience and have gained firm footholds in the modern Chinese economy. They may not be prodigies, but they are still wealthier and far more likely to be investor migrants than your average Zhou.

As a rule, they favor destinations with which they are familiar, typically the country in which they once attended school. Many – especially in the tech sector – dart back and forth between the United States and China to enjoy the best of both worlds; cutting-edge tech and innovation on one side, and huge, uncatered-to consumer markets on the other (these jet-setters, incidentally, are known as “seagulls”).

My personal empirical observation is that sea turtles and seagulls have a penchant for real estate-based programs, probably a consequence of their parents’ financial backing. The sea turtles’ parents, as you may know, got rich in the ’90s and early 2000s in large part thanks to an urbanization trend the likes of which the world had never seen and are unlikely to witness again. Their parents, who have in many cases bankrolled their children’s investor visas, understand and appreciate the real estate asset class (and precious few others) and, so, are not likely to favor, say, the venture capital option.

Sea turtles have an idea of what the world has to offer in terms of lifestyles and liberties, and they – more often than not – have the means to attain it. Though they may look and sound Chinese, they commonly have trouble fitting in among their own back home. This is doubly true for the sea turtles whose rumspringa began at the boarding school age. That combination of factors makes millennial sea turtles the Chinese demographic group that has the greatest propensity to obtain a residency or citizenship abroad.

Luc Lu is a decade-long veteran of the Chinese Investment Migration Industry, founder of several firms in that market, and official partner of Investment Migration Insider, responsible for China-based activities.