China’s Millennials: What Does the World’s Largest Investor Migrant Group Want? Part 2

Mr. Lu’s Tea Leaves

With Luc Lu

A seasoned veteran of the Chinese RCBI industry keeps readers abreast of overarching trends in the world’s biggest investment migration market.

This is the second installment of a three-part series on China’s millennial generation and how it is shaping the world’s largest investment migration market. Read Part I here.

As we enter 2020, even the youngest of those born in the 1980s are in their thirties. In China, this generation is quickly becoming the main driver of the country’s investment migration market. Millennials, here defined as those born between 1980 and 1996 account for about 23% of the overall population. Due to the rapid economic transformation of the country in the years since they were born, China’s millennials are very different, both from their parents and their children (who are just now being born).

Compared to their parents, millennials want very different things from life, work, and – the focus of this discussion – immigration. What worked with Generation X won’t work with Generation Y. This article will contrast millennials with the generations that came before and illustrate how that will change the shape of Chinese investment migration.

Coca Cola and Goji Berries

On December 16th, 1978, Jimmy Carter and Deng Xiaoping signed the Joint Communique on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between the People’ Republic of China and the United States of America, which normalized relations between two countries whose relationship had been anything but normal until then. A few days later, Coca Cola became the first foreign company in more than two decades to be allowed back into China.

Whereas today, an international beverage company might be expected to avoid political affiliation, the Coca Cola companies of the 1950s was one that actively sought to align itself with the American government’s goals of ridding the world of Communism and promoting Democracy. Chinese propaganda, meanwhile, had painted the drinks maker as American expansionism incarnate. In 1950, Minister of Culture Mao Dun warned in the People’s Daily that Coca-Cola’s role in spreading “American civilization” represented a peril on par with the country’s formidable military.

In light of the “baggage” that characterized Coca Cola’s relationship with China, the symbolic nature of the company’s admission into China was unmistakable. In those first days of the Reform and Opening Up period, China’s economy was still reeling from thirty years of planned economy. The dearth of material and cultural wealth was extreme. Coca Cola represented, to the Chinese mind, a casual and carefree culture of leisure from the West. Its entrance in the Middle Kingdom marked the end of an era of trials and hardship and the advent of a new age of consumption.

Chinese millennials may be too young to have experienced pre-Coca Cola China but their parents have made sure they know what it was like. To millennials, therefore, the drink has come to represent globalization, foreign ideas, new ideas, independent thinking, and – more generally – optimism about the future. Coca Cola, in a nutshell, epitomizes the Chinese millennial’s outlook on life.

Another consumer item that’s emblematic of the Chinese millennial’s mentality – though not for the same reason as Coca Cola – is the goji berry, a fruit widely considered to promote health. Everyone can afford goji berries, which the Chinese – who prefer hot drinks to cold ones – like to soak in water in their vacuum flasks and sip throughout the day.

Millennials in China, you see, are health conscious to a degree that seems entirely foreign to their chainsmoking parents. Traumatized by food safety scandals that have included toxic baby milk, rice adulterated by plastic, counterfeit alcohol, and soy sauce made from human hair, China’s millennials are hyper-vigilant about the source of their nutrition. Thanks to lethal levels of air pollution, Chinese millennials have been wearing masks outside since long before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pursuit of health is a top priority among China’s millennials and one of the character traits on which they most markedly distinguish themselves from the generation that came before them.

Focusing on “wellness”, in other words, is one effortless way of capturing the attention of Chinese millennials.

Education still paramount, just not the Chinese kind

I needn’t tell you that Chinese parents, traditionally, focus intensely on their children’s education. Be it in China, Singapore, or anywhere else that has an ethnic-Chinese majority, even the gentlest of parents invariably turn into “helicopter parents” (alternatively, “tiger moms”) when faced with questions of their children’s schooling.

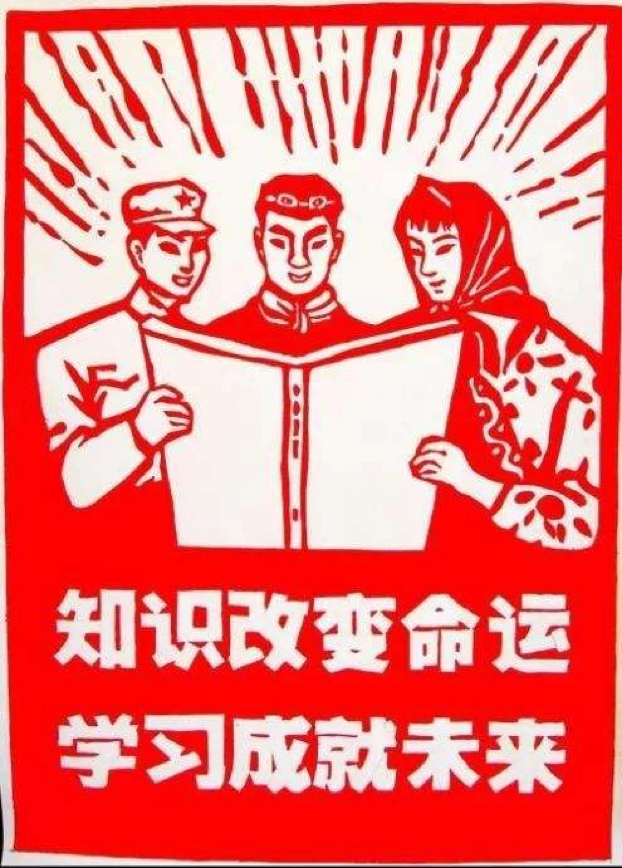

After undergoing the Cultural Revolution in the sixties and seventies, when even attending school at all wasn’t a given, China’s Generation X’ers returned to the school bench with renewed fervor, determined to change their own futures through education. This post-Cultural Revolution period gave birth to the slogan “Knowledge Changes Destiny”, a phrase that became the clarion call for and the basis of the educational philosophy Generation X parents imposed on their millennial children.

Millennials, as a consequence, faced cut-throat competition, immense pressure, and grueling entrance exams at all levels. Each year, about 10 million Chinese teenagers sit the National College Entrance examination – the dreaded gaokao. A tiny share of those students go on to attend elite universities in the big cities. The outcome of 12 years of cramming all depends on your performance on the gaokao, the pressure of which makes the SATs look like a game of Trivial Pursuit by comparison.

Conventional Chinese education is characterized by

- Extreme pressure on the student

- Rote memorization

- Exam-taking

One thing it does not produce is well-rounded critical thinkers.

And this partly explains the common observation that the “star-students” from millennial cohorts did not achieve the professional success everyone expected of them. Instead, it’s often been the laggards who reaped the career rewards and wealth for which the “keeners” were ostensibly destined.

So common is this observation, in fact, that there seems to be a strong inverse correlation between gaokao performance and real-life performance. Personally, I think there are two chief reasons for this: First, the star students – by definition – are far outnumbered by students in the meatier part of the bell curve so that, by virtue of simple probability, there should be fewer “winners” among their ranks.

Second, their higher academic achievements often narrowed the scope of jobs toward which they were funneled, many becoming PhDs rather than entrepreneurs.

Moreover, one characteristic of millennial star students is their inflexible mindset. They may have mastered performance in a controlled environment where the objectives, work methods, and subject matter focused is determined by others, but the same singular focus that allowed them to succeed under those conditions prevented them from gaining practical experience. The real world is nothing like school. Nobody tells you how you should allocate your time or which goals to pursue. You must determine this for yourself. And star students simply have very little experience in using their own judgment.

Average students, on the other hand, are far more confident in leaving their own comfort zones, seeking out their own sources of information, and choosing for themselves what to focus on.

Having observed that academic and professional success appear to be, at best, non-correlated, Chinese millennial parents are questioning the Chinese education system, though not education as such. They still consider learning and knowledge the keys to success, but they are placing more emphasis on what kind of knowledge and learning gives the best results.

Just like their own parents, millennials are becoming “helicopter parents”, just of an entirely different breed. They no longer believe that getting your son or daughter into Tsinghua or Fudan is alpha omega – quite the contrary. They would much rather prefer they attend elite boarding schools in England and Ivy League universities in the US. And they certainly do not wish upon their children the agony of the gaokao.

Stay tuned for the third and final installment in this series.

Luc Lu is a decade-long veteran of the Chinese Investment Migration Industry, founder of several firms in that market, and official partner of Investment Migration Insider, responsible for China-based activities.