Throughout history, governments have weaponized denaturalization to reshape populations, punish dissent, and seize wealth. As new technologies and climate threats emerge, the ancient practice of unmaking citizens is finding fresh applications in the modern era.

This examination traces the systematic removal of citizenship from individuals and groups, revealing patterns that persist from antiquity to modern crises.

Ancient Precedents

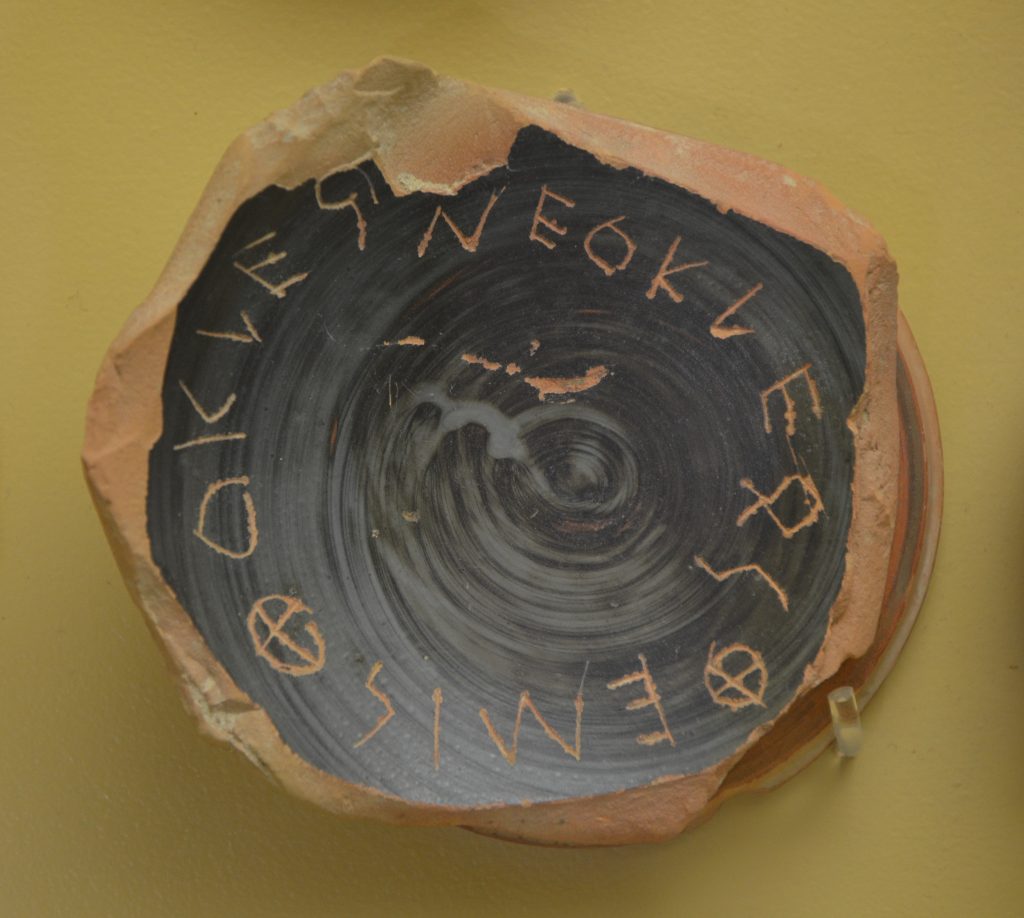

Ancient Athens pioneered formal citizenship and its revocation. The ecclesia exercised this power through ostracism, a process formalized by Cleisthenes in 508 BCE. Archaeological evidence from the Agora includes thousands of ostraka—pottery shards inscribed with names—used in exile votes.

While standard ostracism imposed a ten-year exile, more severe cases resulted in permanent loss of citizenship rights, effectively denaturalizing the individual completely. Pericles’ citizenship law in 451 BCE restricted citizenship to those with two Athenian parents.

A subsequent review removed many from the citizen rolls, as some may have been forced into servitude.

Sparta imposed status loss on those failing to complete military training or contribute to communal meals. Xenophon noted that such individuals became hypomeiones, losing full political rights.

A 464 BCE earthquake triggered a major crisis (including a helot revolt), after which the Spartans became even more stringent about who still qualified for full citizen status.

Some Spartans couldn’t continue meeting the economic or military criteria in the aftermath of the earthquake—farmland was ruined, families lost resources, and the chaos of revolt challenged Spartan control.

As a result, Sparta demoted many from the Spartiate class to lower-status groups, losing political and social rights.

Over time, such demotions reduced the core body of full Spartan citizens, contributing to Sparta’s long-term population decline and illustrating how tightly citizenship was bound to fulfilling military and civic obligations.

Rome also established structured legal mechanisms for citizenship revocation.

The concept of capitis deminutio maxima (the greatest reduction of status) existed as a legal status change that stripped individuals of citizenship, freedom, and family rights. However, this primarily applied to individuals through specific legal proceedings rather than as a mass denaturalization tool.

It typically occurred when someone received enslavement as punishment for serious crimes or capture in war. In 312 BCE, censor Appius Claudius Caecus restructured the citizen rolls, affecting thousands who failed to meet land ownership requirements. The Senate also issued targeted denaturalization decrees, including one in 86 BCE against rebellious Italian allies.

Carthaginian and Qin Dynasty records indicate citizenship revocation as a tool of state control. Carthage’s governing bodies removed status from those implicated in failed military campaigns. Qin legal texts detail how entire families could disappear from household registries, often as punishment for rebellion.

Medieval and Early Modern Period

In the medieval period, modern notions of citizenship and even nations did not exist in the form they do today. Rulers often resorted to banishment or expulsion rather than formal revocations of nationality.

Medieval European monarchies employed status revocation as a means of exclusion. England’s 1290 Edict of Expulsion ordered all Jews to leave, stripping them of legal protections.

Records in the Calendar of Patent Rolls detail property seizures accompanying this expulsion, enriching royal coffers by an estimated £80,000—a staggering sum representing roughly 17% of the Crown’s annual revenue.

Spain’s 1492 Alhambra Decree expelled Jews, affecting tens of thousands. The 1609-1614 expulsion of Moriscos, descendants of converted Muslims, displaced approximately 275,000.

These actions stemmed from state efforts to consolidate religious and ethnic identity while simultaneously allowing the monarchy to expropriate substantial property holdings.

Economic historian Helen Rawlings estimates the Crown seized property valued at over 11 million ducats from expelled Moriscos.

The Ottoman Empire’s millet system categorized subjects by religion, assigning differential rights.

Administrative records show that non-Muslim groups faced citizenship restrictions long before formal European nationality laws emerged.

The Age of Revolution

The French Revolution transformed citizenship into a political status tied to loyalty. The 1789 Decree on Émigrés revoked the citizenship of nobles and clergy who fled.

Registers from the Committee of Public Safety document thousands of people losing rights, alongside extensive property confiscations.

Revolutionary governments auctioned confiscated estates worth an estimated three billion livres, using proceeds to back the new assignat currency system.

Napoleonic conflicts spread these policies.

Naples denaturalized nobles who opposed French rule. After 1814, Spain revoked the citizenship of 32,000 afrancesados who had collaborated with the French.

Prussia’s 1871 nationality laws targeted Polish speakers and socialists, removing thousands from official rolls.

Early Twentieth Century

Mass denaturalization became a state tool for managing ethnic and political identity.

The Ottoman Empire increasingly restricted Armenian documentation, setting the stage for their later expulsion.

The United States Expatriation Act of 1907 revoked the citizenship of American women who married foreign men. State Department records show over 6,000 women suffered this fate in the first decade.

This gender-based citizenship revocation highlights how denaturalization has often disproportionately affected vulnerable populations, particularly women whose citizenship depended on their husbands’ status.

In Australia, the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act led to the loss of voting rights for hundreds of Chinese citizens.

Mussolini’s Fascist regime in Italy enacted comprehensive denaturalization laws. The 1926 law revoked citizenship from political opponents deemed “unworthy of Italian citizenship,” while the 1938 racial laws stripped citizenship from Italian Jews.

The removal of citizenship “became a weapon of political and racial persecution,” noted historian Gadi Luzzatto Voghera. These measures affected approximately 50,000 individuals, forcing many into exile or making them vulnerable to deportation.

The Soviet Era

The Soviet government systematically used denaturalization as a political weapon. A 1921 decree stripped citizenship from Russians who had fled during the Civil War, affecting up to 1.5 million people.

The People’s Commissariat for Finance documented extensive property seizures, particularly targeting religious institutions. Gold and silver from churches alone yielded an estimated 20 million rubles for state coffers.

During Stalin’s purges, citizenship revocation expanded. National Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) records indicate that 1.5 million individuals lost their rights between 1934 and 1939.

The annexation of the Baltic states in 1940 triggered new waves of forced denaturalization, affecting tens of thousands.

The Nazi Regime and Vichy France

The 20th century witnessed the most egregious abuses of denaturalization powers. Nazi Germany implemented expansive citizenship revocation policies.

The 1935 Nuremberg Laws stripped German Jews of citizenship, affecting over 400,000 people. The Reich Interior Ministry orchestrated additional denaturalizations targeting political opponents and Eastern European Jews.

The 11th Decree to the Reich Citizenship Law in 1941 automatically revoked Jewish citizenship upon deportation, affecting hundreds of thousands. Property confiscations escalated, reaching billions of Reichsmarks by the end of the decade.

The Reich’s Finance Ministry created specialized departments that methodically cataloged and liquidated Jewish assets, generating approximately 8.9 billion Reichsmarks—equivalent to roughly 30% of Germany’s annual tax revenue in 1938.

The Vichy French regime, established after France’s defeat to Nazi Germany in 1940, similarly enacted laws denaturalizing certain groups.

The regime revoked the citizenship of approximately 15,000 naturalized citizens, primarily targeting Jews who had become French citizens after 1927. This collaboration with Nazi denaturalization policies further demonstrates how citizenship revocation often precedes broader human rights abuses.

These policies extended into occupied territories, denaturalizing Jews in annexed Austria and German-occupied Poland.

The Nazi approach to denaturalization represents the most systematic application of citizenship stripping as a prelude to genocide, revealing how the removal of legal personhood often precedes mass atrocities.

Post-War Population Transfers and Legal Reforms

After World War II, millions lost their citizenship. Potsdam Conference protocols facilitated the forced relocation of 12 million ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe.

Czechoslovakia’s Beneš Decrees revoked the citizenship of three million Germans and 100,000 Hungarians. Poland expelled 3.5 million Germans, while Yugoslavia denaturalized and expelled 300,000 ethnic Germans.

These post-war population transfers represent the largest coordinated multi-state denaturalization effort in modern history, illustrating how victorious powers often use citizenship revocation to punish perceived collective guilt.

The actions of the Nazi era sparked new international principles against arbitrary citizenship deprivation.

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights established that “everyone has the right to a nationality” and that “no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality.”

While these principles did not completely eliminate denaturalization, they significantly constrained its use in democratic nations, establishing citizenship as a fundamental right rather than a revocable privilege.

Decolonization and Revolutionary Regimes

British India’s partition in 1947 created a citizenship crisis, displacing 14 million people. Burma’s 1962 military regime revoked the citizenship of hundreds of thousands of Indians.

In Uganda, Idi Amin’s 1972 expulsion of 80,000 Asians led to mass denaturalization, a policy echoed in Kenya and Tanzania. The 1964 Zanzibar Revolution resulted in the overthrow of the Sultan and the targeting of the island’s Arab and South Asian populations.

The new government revoked the citizenship of thousands, leading to mass expulsions and killings. Between 5,000 and 15,000 Arabs and South Asians lost their citizenship status, and many were forced to flee to Oman and other countries.

Iraq’s systematic denaturalization of Feyli Kurds in the 1970s-80s illustrates citizenship revocation based on ethnic targeting. The Ba’athist regime revoked the citizenship of approximately 300,000 Feyli Kurds, a Shi’ite Kurdish minority, labeling them as “Iranian” despite centuries of residence in Iraq.

This action coincided with their expulsion to Iran, property confiscation, and in many cases, the execution of working-age men. Human Rights Watch documented that “entire families were loaded onto trucks and dumped at the Iranian border.”

The Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia (1975-1979) effectively nullified citizenship for the entire population. Through the abolition of money, private property, and legal systems, they created what historian Ben Kiernan called “a complete suspension of citizenship rights.”

Urban citizens moved forcibly into the countryside, and all forms of previous identification disappeared. The entire concept of legal identity gave way to categories like “new people” and “base people,” erasing traditional citizenship protections.

Apartheid and Racial Segregation

South Africa’s apartheid regime created one of the most extensive denaturalization schemes through the Bantustan system. The 1970 Black States Citizenship Act forced millions of Black South Africans to become citizens of nominally independent “homelands,” stripping them of South African citizenship.

This administrative fiction allowed the regime to claim that Black South Africans constituted “foreign nationals” even when working in South African cities.

By 1990, over four million people had undergone denaturalization through this system, which political scientist Mahmood Mamdani described as “the ultimate form of legal segregation.”

The Bantustan strategy represents perhaps the most legally sophisticated denaturalization scheme, as it allowed the apartheid regime to claim it avoided discriminating against its own citizens while simultaneously denying rights to the majority of the country’s inhabitants.

The Cold War

Communist governments used denaturalization to control dissent. East Germany’s approach to citizenship for those who fled to the West proved more nuanced than simple denaturalization.

While the German Democratic Republic (GDR) did enact laws allowing for citizenship revocation, historical records show they often maintained that escapees remained citizens. This allowed the regime to claim them as their own for propaganda purposes while simultaneously punishing them through property confiscation and criminal charges for “illegal border crossing.”

The 1967 Citizenship Law formalized this approach, creating a contradictory status where escapees existed both as claimed citizens and denied citizenship protections. Cuba’s 1961 Nationality Law targeted emigrants deemed counter-revolutionary, affecting hundreds of thousands.

Soviet Dissolution

The Soviet Union’s collapse created the largest stateless population in Europe since World War II. Latvia and Estonia initially denied citizenship to 730,000 Soviet-era Russian settlers.

In Slovenia, a 1992 administrative action erased 25,000 citizens from official records, leaving them stateless. These individuals, known as “the erased,” were primarily people of non-Slovene ethnicity from other former Yugoslav republics who had been legal citizens but lost their citizenship status after Slovenia’s independence.

Ethnic Targeting in the 1990s

Bhutan’s expulsion of ethnic Nepalis (Lhotshampas) demonstrates how citizenship revocation often accompanies ethnic cleansing. The government implemented a new citizenship law and census that retroactively applied strict documentation requirements.

When many ethnic Nepalis failed to produce the required documents, approximately 100,000 lost their citizenship and faced expulsion to refugee camps in Nepal.

The International Organization for Migration noted that “overnight, generations of legal citizens became stateless.”

Many of these refugees remained in camps for over two decades, creating one of the most protracted refugee situations in Asia and highlighting how citizenship revocation can create intergenerational statelessness.

Contemporary Cases

The Dominican Republic’s 2013 Constitutional Court ruling retroactively stripped citizenship from approximately 200,000 people of Haitian descent.

The court’s decision (TC 168-13) reinterpreted the constitution to deny citizenship to anyone born to undocumented migrants since 1929, despite the country’s long-standing birthright citizenship rule.

Despite international backlash and a 2014 law offering naturalization to some affected individuals, many still struggle with statelessness.

Myanmar’s 1982 Citizenship Law excluded the Rohingya, rendering 1.1 million stateless. This wasn’t a single denaturalization event but a gradual legal erosion of rights that, by the 2000s, left most Rohingya Muslims effectively stateless, paving the way for the ethnic cleansing that occurred in 2017.

Contemporary denaturalization laws have expanded in many Western democracies.

Since 2006, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and several European countries have enacted legislation allowing citizenship revocation for dual nationals who obtained citizenship fraudulently or engaged in activities deemed threatening to national security.

The Ultimate Tool of Control

The modern era presents new risks to citizenship rights. Technology has introduced new mechanisms for citizenship exclusion.

India has linked its Aadhaar biometric system to authentication failures affecting access to services.

Climate change may also create stateless populations. The Republic of Kiribati has purchased land in Fiji in anticipation of future displacement.

The economic dimension of denaturalization remains a consistent theme across centuries.

From medieval expulsions that enriched royal treasuries to modern asset freezes targeting political dissidents, the revocation of citizenship frequently coincides with property confiscation.

Economic historian Emma Rothschild estimates that governments worldwide have expropriated assets worth over $350 billion through citizenship revocation schemes since 1900.

The tension between national security concerns and the principle that citizenship is a fundamental right continues to shape debates about denaturalization. While international law has curbed arbitrary citizenship revocation, it has not eliminated the practice entirely.

The past century demonstrates that citizenship revocation remains a powerful tool for population control and political repression.

Understanding these historical patterns proves essential to safeguarding citizenship rights today.

Disclaimer: This article synthesizes historical information from a wide variety of academic and institutional sources. The historical accounts, figures, dates, and quotes presented draw from scholarly works on citizenship law, political history, and human rights documentation. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, some numerical estimates (such as the total number of people affected by specific denaturalization events) are based on the best available historical scholarship and may vary among sources. The economic figures cited (such as property valuation and asset seizures) similarly reflect scholarly estimates where precise contemporaneous accounting is unavailable. The examples presented herein are intended to illustrate historical patterns rather than to make legal claims about specific contemporary situations. This article does not constitute legal advice, nor does it take a position on the legality or justifiability of any specific government’s denaturalization policies.