15 Million Stateless Individuals – An Interview With Kristy A. Belton

Statelessness is an underexplored topic in the CIP-world. Recently, however, some CIP-jurisdictions have floated proposals to permit the naturalization of stateless investors, bringing more attention to the phenomenon. On IMI, some have proposed citizenship by investment as a form of insurance against statelessness.

But why does statelessness occur, and how big of a problem is it?

Kristy A. Belton is the author of Statelessness in the Caribbean: The Paradox of Belonging in a Postnational World. A native of the Bahamas, Ms Belton is today the director of professional development at the International Studies Association.

Speaking to IMI, Ms Belton details the the current nuances and emerging challenges surrounding statelessness within the international community.

In your work, you detail that the inattention to the stateless is partly a result of the possibility of people being made stateless in non-conflict and non-crisis scenarios and, thus, the issue ‘flies under the radar’ of public attention. Is this changing now with the rise of the digital media landscape or is it the same as its always been?

Digital media allows us to see things unfold in real-time. We are able to keep abreast of occurrences – whether in the form of tragedies, such as happened to the stateless Rohingya of Myanmar, or in the form of other human rights violations, such as happens to the children of stateless migrants around the globe.

That said, digital media is, as you put it, a landscape. We still need devoted actors (whether journalists, practitioners, advocates of various stripes, the stateless themselves when they are able) to keep the information coming, to keep the water running through the valve, so-to-speak. Too often – and this is not specific to digital media, but to human interest and attention in general – we find a story, it has our attention for a little while and then “life goes on.”

But these very real stories of rights infringements, social (in)action, injustice and the like are still being lived every day by these people. We have to keep adding our brush strokes to the landscape. We cannot let the painting dry.

Overall, how does the track record of democratic states compare with non-democratic states in dealing with statelessness?

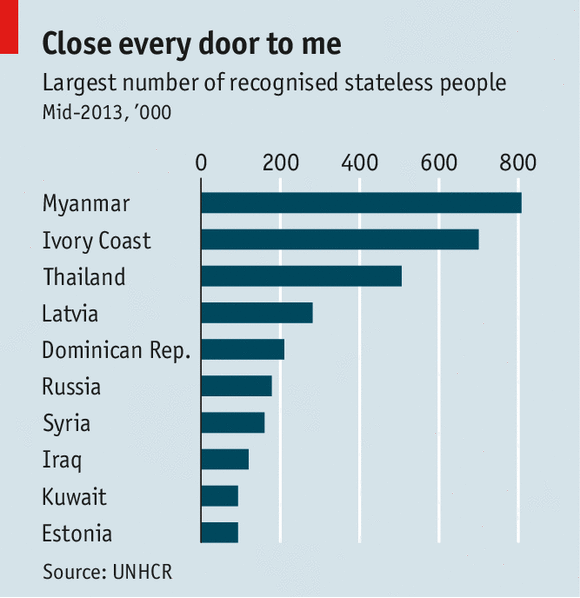

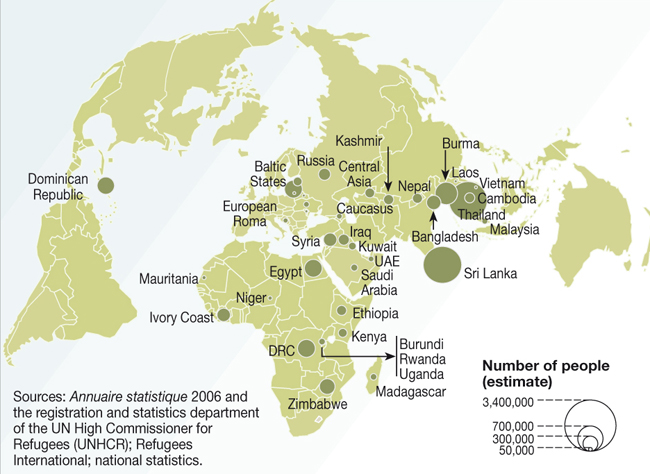

Statelessness is not something that only happens to people who live in crisis or in conflict situations. Stateless people are everywhere: Europe, the Caribbean, Southeast Asia, parts of Africa. Many are born into so-called democracies whose citizenship laws simply do not capture them as “citizens.” So they might become stateless because of a “legal loophole.”

Take, for instance, the following scenario. A child is born in a country to foreign parents. The country the child is born in does not allow the child to acquire citizenship through birth on the soil. The child’s parents hold citizenship from a country that does not allow its citizens to pass on citizenship to their children born overseas. The child becomes stateless. This child, although not born in a non-democracy or in a country that is undergoing conflict of some sort, will face an uphill battle in simply trying to live within a system that insists on citizenship from somewhere as a marker of personhood.

In terms of the track record question, this could be answered in various ways depending on how one defines “dealing with” statelessness. If “dealing with” statelessness means ratifying the statelessness conventions or verbally touting a “buy-in” to regional agreements on eradicating statelessness, then the democratic stripe of a country does not really matter. Democracies and non-democracies alike pay lip service to the ideal of eradicating statelessness globally, but democracies appear more likely to use the words we would expect of governments that uphold the principles of equality and justice.

When it comes to the actual practice, however, of ensuring people obtain citizenship in the most transparent, efficient and humane way possible, governments of all persuasions have work to do. I would argue, however, that the most work is in the post-receipt of citizenship stage. To “deal with” statelessness, really deal with it, you have to work on inclusive citizenship.

Whether democracies or not, we have to ask what are the governments doing to ensure that people who now have formally become citizens are actually able to access services, receive basic protections, and enjoy rights? How does the political, civil, legal and socio-economic exclusion that they have undergone suddenly translate into inclusive citizenship?

Is there a reason you can envisage why someone would want to become stateless?

I focus on people who have been forced into statelessness, and cannot therefore readily speak to why people would voluntarily renounce the citizenship they hold. I can posit a few possibilities, however. As a matter of principle, some may reject the premises of the State system or dislike the policies (whether foreign, economic or otherwise) of their State of origin. Others may want to evade a particular responsibility, such as paying taxes. While others may simply want to live off the radar, so-to-speak.

I am sure that each person who has chosen to become voluntarily stateless will have a different reason. In any event, I think the context, or State boundaries, within which one makes the choice to become voluntarily stateless matters.

From a quality of life perspective, it is less onerous to choose to become stateless in a country with a democratic tradition where equality, justice, and law and order are valued, as opposed to a country where such a tradition does not exist. An individual is less likely to be indefinitely detained, persecuted or face blatant violations of their human rights in countries where democratic values still hold strong and where, importantly, an active civil society exists.

How likely do you think it is a hostile nation could ‘use’ someone made stateless as a weapon to gain access to another nation in the future?

Stateless people are largely immobile in the sense that they cannot freely cross international borders. Unlike citizens, they do not exist in the eyes of the State and its laws, they consequently have great difficulty in securing authorized travel documents.

In some cases, fear of what could happen to them if they were to move around (even within the country of their residence), renders them immobile. So I do not think the posited scenario is likely. The vast majority of stateless people simply want to secure citizenship of the country of their birth and/or residence. In my work with stateless people, they all want to be citizens. They want to have the same opportunities and rights that we, as citizens, do.

You also write that the stateless must have a right to choose to belong in the community of their birth. This sounds logical but it does it not also run up against the efforts by many nations in recent times to do away with jus soli?

While a few countries may have set about trying to limit their jus soli provisions, we have to remember that jus soli is not the norm globally. A little over 30 countries, less than 20% of the world’s States, offer unrestricted citizenship acquisition through birth on the soil.

Just because a particular political form has arisen over the last few hundred years (the current international system of States), however, does not mean that this is the way people will organize themselves in the future. The fact that over 15 million are stateless within a system that mandates formal political belonging to a State illustrates the ineffectiveness of this way of ordering people.

Christian Henrik Nesheim is the founder and editor of Investment Migration Insider, the #1 magazine – online or offline – for residency and citizenship by investment. He is an internationally recognized expert, speaker, documentary producer, and writer on the subject of investment migration, whose work is cited in the Economist, Bloomberg, Fortune, Forbes, Newsweek, and Business Insider. Norwegian by birth, Christian has spent the last 16 years in the United States, China, Spain, and Portugal.