The Economic Roles of Investment Migration: Part 1 – The Entrepreneurial Succession Crisis

Tajick’s Take With Stephane Tajick

A seasoned researcher on RCBI, Stephane Tajick analyzes global shifts in the investment migration industry.

Five years ago, I still saw the investment migration industry as in a state of “childhood.” A relatively young sector that was getting bigger but still was far from reaching its potential. Recently, after years of growth, it’s as though the industry has taken the step into the turbulent years of adolescence, where our “parents” are not sure what to do other than grounding us.

Some children are problematic, and some parents are clueless, but what’s clear is that this teenager has not taken the path his governing parents had in mind.

The optimal purpose a government can find for investment migration is channeling IM funds toward strategic sectors or projects that investors traditionally shun due to their high-risk or low-return nature. The return is rarely the primary motivation for an immigrant investor; it’s secondary. The primary reason is the acquisition of legal status in the jurisdiction.

Finding the optimal economic use for investment migration would be a huge step forward but would only solve some predicaments. Many governments are still too “primitive” to work efficiently. Whereas the world’s leading corporations extensively use data to guide their every move, most government branches barely track the performance of their IM programs or require reviews every few years to determine if they are still on course.

Investment migration programs are economic development programs and should reflect and adapt to the country’s economic indicators with great attention and elasticity. Suppose the Portugal Golden Visa’s purpose was to strengthen the real estate sector after the Eurozone crisis, like most other EU Golden Visas at the time: In that case, it should have started capping and reducing residential real estate purchases in Lisbon by 2018, when the capital had already recovered, rather than excluding these property markets altogether in 2021.

That three or four-year lag between a program’s obsolescence of purpose and its renewal and adaptation is common among investment migration programs. It’s typically caused by a lack of data and intel gathering by the responsible government branch, often an immigration administrative unit without the required expertise to run an economic development program efficiently.

The legal structure of the program can also compound the problem: Too many changes to the program can only be done via legislative amendments. That is why the original legal framework of the program is critical. If you need a Parliamentary vote every time you need to make small adjustments to the program, the program will – of course – end up outdated and unsuited for current economic needs.

As the EU governing bodies have shown, parents can be quick to blame their kids while remaining blissfully unaware of their own shortcomings. Industry experts have a role and responsibility to help improve governance, as expertise cannot be created out of thin air. And we hope the governing bodies will have the wisdom to seek it.

We are starting a series on investment migration’s optimal role in supporting world economies in the coming decade. It’s hard to overstate investment migration’s role in solving these issues. We will cover the following four tasks investment migration programs can perform for economies around the world:

- Entrepreneurial succession: A generational challenge

- Micro-targeted real estate revival

- Reducing sovereign debt

- Post-landing economic impact

Entrepreneurial succession: a generational challenge

The Tech Generation

As a French expat living in Canada for over 25 years, I looked forward to returning to Paris in April for a vacation and taking my spouse on a romantic escapade and tour of the countryside. Spring in Paris is lovely. Unfortunately, the intense protests following the change in retirement age made me revisit my plans. Violent demonstrations and pictures of garbage everywhere are not that lovely. For many onlookers in North America, this is the French acting entitled again, moving the retirement age from 62 to 64.

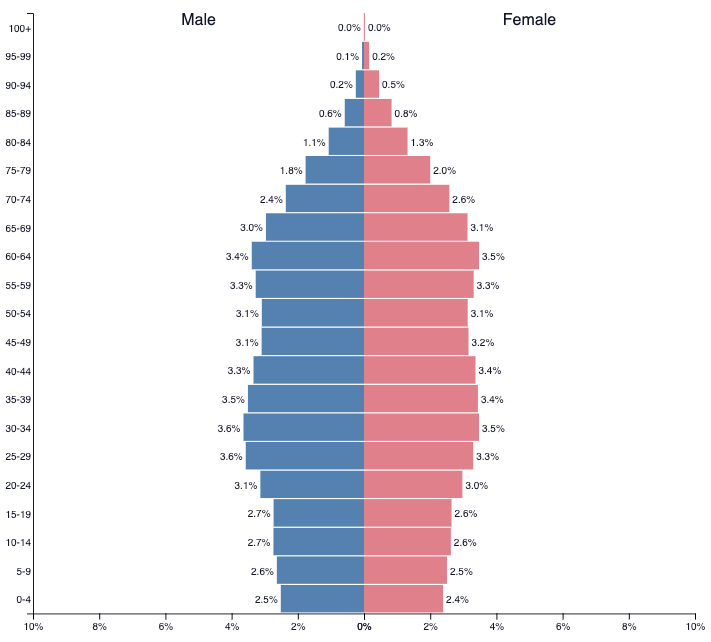

Even if we were to brush off this specific situation, we’d still come face to face with deeper issues that confront most Western countries: An aging population and a growing fiscal deficit. People live longer, we have low fertility rates, everything costs more, and we don’t have the money, so what do we do? Raising the retirement age seems like a simple solution.

Enter the 2019 Covid pandemic. During those few years, society took giant technological leaps because of the pressing need to do everything remotely. Today, staying competitive will be increasingly challenging if your business didn’t jump on that tech bandwagon. Individuals are the same. Many older folks find learning and navigating new apps and software hard. For many jobs today, even those unrelated to IT, you can slowly become obsolete if you struggle with the daily use of technology.

An increasing proportion of our aging workforce is losing value in the marketplace because they can’t adapt to the use of technologies many young people (“digital natives”) find intuitive.

The way our tech-oriented economies are going forward, as a general rule, workers who are tech-savvy will thrive, while those who are not will struggle. Based on that, older workers will feel pressure to retire earlier rather than later.

This statement clashes with the variable on the opposite end: The fiscal deficit and shortage of labor. In countries with low unemployment rates, you’ll end up with older people working in supermarkets and young ones in offices (if I were to caricature the issue). These problems will become critical challenges that Western economies will face in the next decade.

This brings us to another critical challenge that will go from bad to worse: Entrepreneurial succession in advanced economies. Retirement-bound business owners are looking for someone to take over their businesses. In many cases, only investor migrants can fill the role.

The baby boomer crisis

In 2010, Canadian researchers published a report titled Entrepreneurial Succession in Canada. The report was grim: “75% of all business owners will struggle to find a successor to their business (a family member, employee, or buyer)”. If that were to happen, those businesses would gradually close down, and billions of dollars would disappear from the economy every year.

The main culprit is the demographic issue plaguing most Western countries. The Baby Boomer generation is retiring en masse, and the younger generation needs to be more numerous. This is where immigration comes in. Countries like Canada use immigration to compensate for job vacancies, but little is done to find immigrant entrepreneurs to purchase Canadian businesses from the baby boomers.

The issue is much more severe outside the large urban centers. People with businesses in small communities, such as factories employing a sizeable number of locals, tend to close down when the owner is incapacitated or dies from old age.

The 2019 COVID pandemic was a business serial killer that worsened the Entrepreneurial Succession problem. The significant technological leap imposed on society and the business world left many with a painful choice: Adapt or become obsolete. With all the Covid related temporary shut-downs, restarting your business after years of hiatus in your 60s or 70s could be painfully hard.

In Canada, all new reports on Entrepreneurial Succession are talking about “waves” of business transitions, highlighting the dramatic shortage of buyers. An estimated “$2 trillion in assets are set to change hands within the next ten years, and only a fraction of business owners have a formal succession plan.”

All the reports are recommending a coordinated government effort to attract immigrant entrepreneurs for help. This is not a problem that Canada alone faces, but likely every similar Western country with a comparable economy and demographic, from Canada to New Zealand, the UK, Germany, Japan, and many more.

Entrepreneurial Succession poses a serious challenge that only investment migration can solve. I have been voicing this concern for the past decade. Seven years ago, I was asked by the Quebec Immigration Ministry to advise the team responsible for redesigning the Quebec Immigrant Entrepreneur Program. This was already something I strongly highlighted, with a strong focus on regions outside large metropolitan areas and the involvement of the private sector in the advisory process.

Although many of my recommendations were followed, the QIE program itself never took off due to an extremely long processing time (a consequence of quotas), rendering the program dead on arrival. But over the years, these were constant recommendations on my part:

- Set up an entrepreneur/investor program with the option to purchase an existing business.

- Get private sector people onboard, especially those with expertise and added value

- Find ways to provide financing and business support to those new business owners.

- Provide incentives to channel investment in the regions and outside the main economic centers.

For such programs to be effective, a coordinated effort from both government and strong public/private sector partnerships is necessary. This can’t be only an isolated immigration effort; it requires coordination from multiple government levels and actors. The need for brokering, financing, and mentoring is essential for such a program to reap results.

Entrepreneurial Succession is already a trillion-dollar challenge for every advanced economy. And in my view, the number one problem that only investment migration can solve.

Would you like to contribute an article to IMI?

IMI relies on a global network of specialist contributors to keep our audience abreast of investment migration developments in every corner of the globe. If you have special expertise, or you’d simply like to voice your opinion, why not contribute an article to IMI?

To learn how to proceed, see our Article Contribution Guidelines.

Stephane Tajick is a researcher in the field of investment migration, the developer of the STC database on more than 200 residence and citizenship by investment programs worldwide. He is a regular columnist at Investment Migration Insider.