The Compromise That Reduces Political and Popular Opposition to CBI

Tajick’s Take With Stephane Tajick

A seasoned researcher on RCBI, Stephane Tajick analyzes global shifts in the investment migration industry.

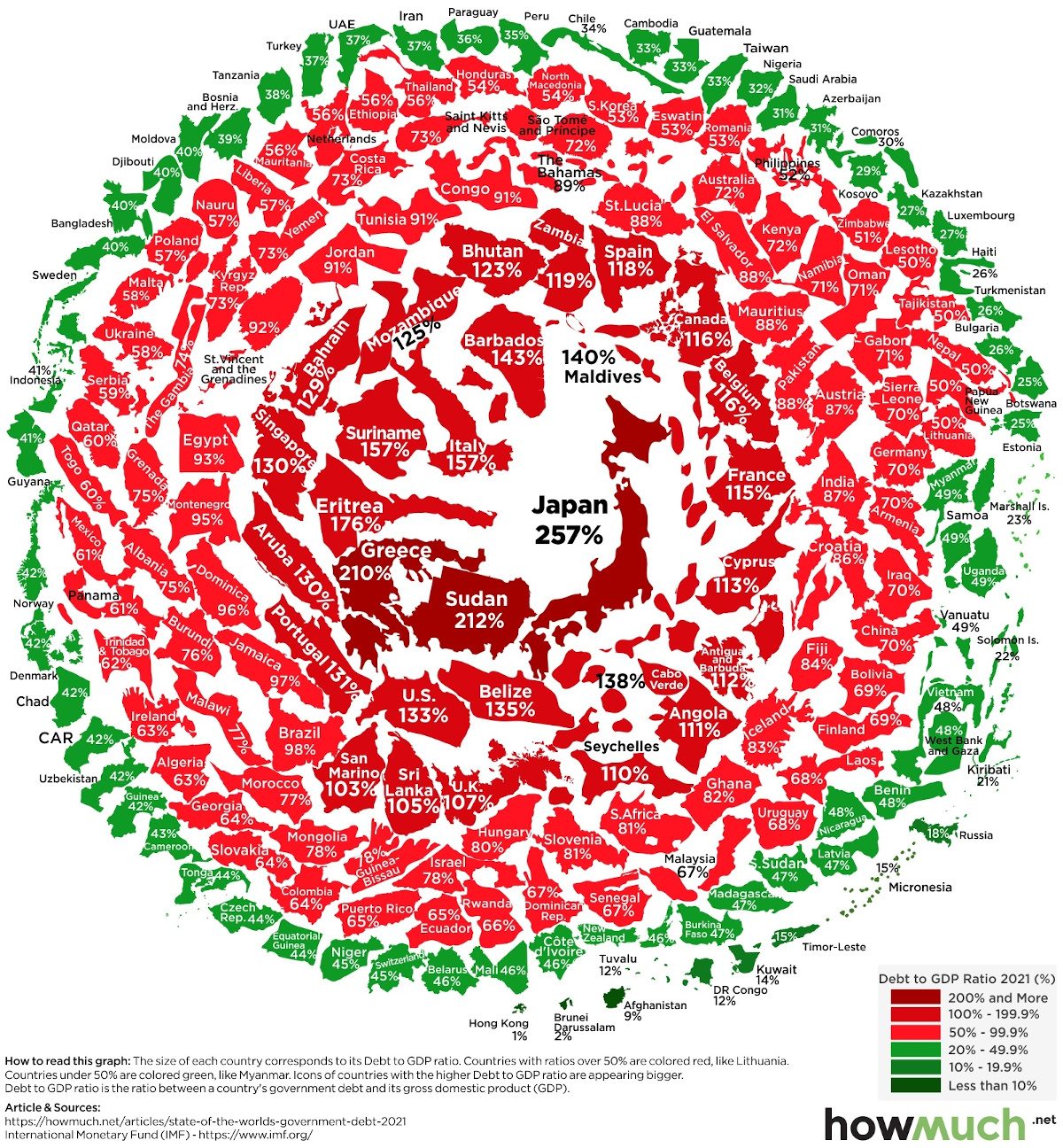

In the past year, there have been growing whispers of an EU country contemplating the launch of a citizenship by investment program (CIP). It’s not hard to imagine why: Government debt has ballooned since the start of the pandemic.

Even with the drop in lending rates, it’s hard to imagine the situation being sustainable. The worldwide agreement announced last week on tax harmonization was hailed as a significant step towards “reducing tax base erosion”. Most macroeconomic policy observers expect taxes to increase in the coming years. But for many European countries, raising taxes will do little to bring public finances back from the overleveraged brink.

The sale of public assets (including citizenship) to stave off insolvency

I have always been a proponent of citizenship-by-investment programs as a fiscal measure. Governments can convincingly justify a CIP when the economic situation is dire and the economic impact of a CIP is significant. Haunted by the specter of insolvency, governments, like any other economic entity, naturally react by putting up for sale what liquefiable assets remain at their disposal. A country might start selling some of its lands to the private sector, or by privatizing government-owned companies and resources.

Depending on the country, citizenships may be one such liquefiable asset. Christian Kälin coined the term “sovereign equity” (as opposed to sovereign debt). Selling your country’s citizenship (presuming it is, in fact, a marketable asset, which is the case for Latvia, for example, but not for Afghanistan) is a cash-generating solution like any other to stave off insolvency. Certainly, it is preferable to counter-insolvency measures like reducing public services or raising taxes.

Some may consider the sale of citizenship demeaning but, surely, it’s better than economic collapse. I was always vocal about having the EU recognize citizenship-by-investment as an alternative economic policy to be used as a ”last resort” and a temporary measure with specific guidelines and objectives. After all, EU citizenship is a common asset shared by all its members. Selling EU citizenship when you’re a rich country looking to get richer is more difficult to justify, in my opinion. If you’re an EU country heading dangerously towards a fiscal cliff, a citizenship-by-investment program should at least be part of the discussion. Overborrowing cannot be the only “solution”.

I wrote a few years ago that an EU CBI can potentially raise half a billion dollars in annual donations. That’s probably an understatement of the true potential but, in any case, for a small country, half a billion or a billion can do wonders. But for the average EU country, this a drop in the bucket compared to the national debt. CBI, therefore, becomes a battle between economic and political benefits. I have yet to hear of a European CIP that boosted the ruling party’s results at the polls. To bring forward a CIP and still be in power after the next election, you either need a lot of political capital (electoral margin) or, of course, the autocratic ability to steer elections.

Economic benefits alone are not enough. You need to account for sentiment too

A recent event from the world of sports reminded me of how, even when the economic benefits are incontrovertible, the public will reject sensible proposals if they consider them emotionally problematic:

In April, 12 of the leading European football clubs announced the launch of a Superleague outside the traditional framework of UEFA. It was a bold move that had been in the works for years, but the drastic need for cash gave it the final push it needed. The pandemic had hammered the sports world and the leading clubs were hemorrhaging money at a frightening rate. The Superleague was supposed to be played in parallel with the other UEFA and national leagues and inject billions of dollars into the founding clubs. The concept was backed by Morgan Stanley. The group thought it had found a fiscal solution to their problem, but what they failed to foresee was the massive opposition from the football community. It took only a few days for the proposal to collapse.

All the British clubs distanced themselves from the project after fans worldwide objected that such a competition – without sporting merit and solely based on greed – might see the light of day. Mass fan protests rapidly took place in front of the club stadiums. In the case of the English clubs, the fans were mostly right, as these teams are owned by private individuals that had been making a quick buck. But in Spain, where legendary clubs like Real Madrid and Barcelona are owned by the “socios” [members], there was a real fear of an economic downfall if a remedy was not found.

In hindsight, Superleague’s proponents did not consider there might be a public outcry over their controversial project. They were blindsided by the response, and by then it was too late for them to drive the narrative. The project ended up dead-on-arrival, and what was supposed to be a solution turned out to be an expensive mistake.

I can imagine the public outcry in certain EU countries, who are madly proud of their heritage, should their governments launch a CIP. There would be mass protests followed by mass resignations from the government. Launching a CIP in Europe is a dangerous game, especially when there are alternatives.

As Portugal has shown, you can simply provide a flexible path towards citizenship instead. The future of RCBI in Europe may well lean towards the Portuguese model rather than the Maltese one. Reducing years of residence towards naturalization is very common in the naturalization laws of EU countries. They often are reduced for reasons of marriage, ancestry, historical affinity, and so on. It doesn’t take so much political credit to amend your laws so investors can be naturalized after 3 years instead of 10 years. Have them pass a civic and language test if needed, but let the physical presence requirements be dictated by their resident permit, as is the case in Portugal.

This formula may be the compromise that will satisfy both the public treasury and sentiment.

Stephane Tajick is a researcher in the field of investment migration, the developer of the STC database on more than 200 residence and citizenship by investment programs worldwide. He is a regular columnist at Investment Migration Insider.