To Gain Popular Acceptance of RCBI, Draw a Direct Line Between Investors and Their Contributions

Due Process

With Michael Krakat

Legal Scholar Michael B. Krakat observes investment migration through the lens of international, constitutional, and administrative law.

It isn’t possible to avoid conflating residence and citizenship by Investment (RCBI) with matters of identity or morals. Rather than antagonizing those who mischaracterize the transactional laws with citizenship’s identity side, the commercial sale of passports can heighten sales as well as the morale of the transaction, feeding two birds with one scone (a vegan’s version of the familiar idiom).

For sustainable investment migration to enjoy local-global acceptance, the money trail of the investment should be transparent at all times. Migration-related investments should be direct rather than abstract. Based on investment migration examples such as in the UK, US, New Zealand, or Australia, other places with residence and/or citizenship by investment options could benefit from direct investment in particular business enterprises or property. This type of investment could then extend into other projects, creating special links between the investor and matters of particular relevance to the selling polity.

In my writings during the Investment Migration Council’s pre-COVID academic days, I have long argued that these “extended links”, beyond businesses or property, could entail any and all matters local and global. They could help make both the immigrant investor and the selling country good global citizens, making RCBI more sustainable. This could go so far as to invest in precious musical instruments, or artwork, or matters of both national and global interest. Whatever the focus of the investment, it will attach to both the passport selling polity – showcasing an interest in things that matter – as well as to the readiness of the investor to associate with issues of relevance.

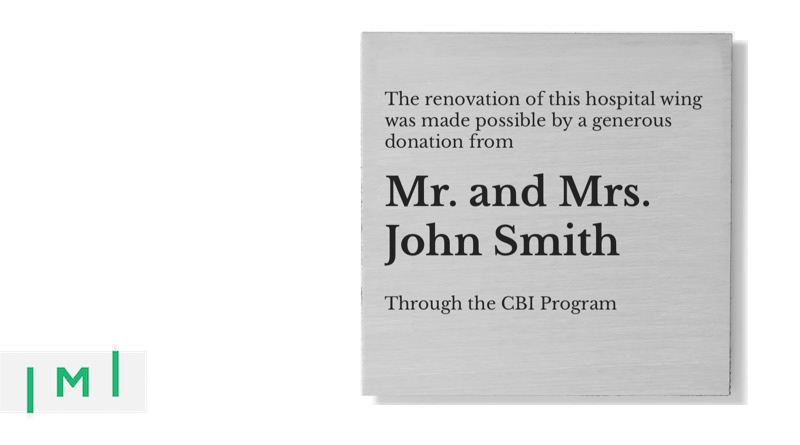

Drawing a direct line from CBI participants to the impact of their contributions

For Vanuatu, I have been arguing that direct conservationist investment into local businesses such as cyclone shelter, water purification, lagoon cleansing, or other matters pertaining to the safeguarding of flora and fauna, should be considered. For example, the Dugong Sea Cow preservation project. These are local matters that find their expression also in the UN’s global sustainability goals, including sustainable migration.

In this way, a passport purchaser may choose to become publicly associated with things that matter most. The cost of that positive association could be included in the initial price, or form that initial price in its entirely, or – as modeled by carbon offset donations – be included on top of the initial price.

The name of the investor could become linked to a particular project of generally accepted or acceptable relevance. Think: “The Zhang Family Reforestation Zone” or the “The Al Mahmoud Center for Biodiversity”. Such investors would no longer be faceless and the revenue they generate for government coffers would no longer be abstract. Instead, the money would be purposefully assigned to particular projects and the contributions attributable to particular individuals.

There could even be a choice of project for the purchaser at the time of purchase. In other words, the visa- or citizenship purchaser could choose, at the time of the transaction, with which project the purchase and their name(s) should become associated if the information is made public.

While transactional, CBI can still be popularly palatable

Of course, in high-tier citizenship by discretion – such as in Peter Thiel’s New Zealand naturalization – the bundle of investments, donations, and commitments are more individualized than the more transactional and abstract purchase in citizenship by investment (CBI).

Where the costs and requirements are clearly advertised, and a purchaser is found responding to the invitation to contract (invitatio ad offerendum), a contract forms and there is a commercial transaction rather than a donation. CBI is an exchange, not a donation. Unlike discretionary and highly individualized naturalization by decree, CBI is, generally, available to anyone who is able to pay the price and has a clear record.

What is often problematic with CBI are the attributes with which it is associated. That includes the aforementioned abstractions but also processes that aren’t adequately subjected to scrutiny and transparency. It is in the abstraction of the purchaser, who may be viewed as a faceless investor, that the process of citizenship acquisition runs the risk of being conflated with the political-moral identity that is traded or commoditized, and, finally, the arrival of the funds and their designation to the general revenue or, at worst, their potential or actual misappropriation.

Optics matter

By the same token, what is publicly associated with RCBI is what matters most. It is its reputation that will determine its continuing function as a system pertaining to personal choice in global mobility and relocation. Local-global links beyond the transaction matter: RCBI as direct investments into things that matter can become the next level of sustainable investment, from both individual perspectives as well as the lens of public acceptance.

The opinion and acceptance of RCBI in the eyes of the existing citizenry of other direct investors or those ordinarily naturalized or born in the polity as well as the world at large matters, whether the industry likes it or not. The holistic perspective toward RCBI will extend it beyond elitism, but will certainly not take away from RCBI’s valuable individualist (and, at times, libertarian) perspective that can in this way be placed in essential balance with collective utilitarianism.

What I suggest, in other words, is not to collectivize RCBI, but rather to create references that heighten the understanding of RCBI as transparent and valid means to valid ends, not taking away from the spirit or RCBI individualism. Political goodwill is needed for making much-needed decisions in RCBI reform, bringing RCBI to the next level, and extending its scope.

Michael B. Krakat is a lecturer and coordinator for comparative Public law – International, Constitutional and Administrative Law – at the University of the South Pacific at Vanuatu and Fiji campuses. Michael is also a researcher at Bond University – Queensland – and Solicitor at the Queensland Supreme- and the High Court of Australia. He also is an academic member of the Investment Migration Council. He can be contacted at michael.krakat@usp.ac.fj.