Is Vietnam the next big market for investment migration?

China and Russia are the world’s largest markets for residency and citizenship by investment, and they will likely remain so for quite some time. It’s natural, then, for investment migration companies to focus a great deal of their efforts in these critical regions.

But because Russians and Chinese have been investing their way into residence permits and citizenships for decades already, those markets are mature and relatively saturated. As an example, China’s Guangdong province alone, it is said, has more than a thousand investment migration firms. There will never in human history be another China; that ship has sailed.

But there are other ships, with plenty of tickets left.

What if you’re an up-and-coming firm wanting to carve out a share of a new frontier market rather than take up competition with the behemoths in established markets? What’s the next colossal market, where it’s still early days and the going is still good?

For the benefit of enterprising whipper-snappers everywhere, I’ve conducted a quick-and-dirty, back-of-the-napkin analysis to find out which market has the greatest potential for investment migration companies in the years to come.

To be a big market for residency and citizenship by investment, a country needs the following four components:

- A large population

- Lack of liberty (limited political freedoms and property rights, lack of safety/stability etc)

- Considerable travel restrictions

- A high number of HNWIs

By method of elimination, we should be able to come up with an answer. Below is a list of the world’s 20 most populous countries.

China – 1.39bn

India – 1.32bn

United States – 325m

Indonesia – 261m

Brazil – 207m

Pakistan – 207m

Nigeria – 193m

Bangladesh – 163m

Russia – 146m

Japan – 126m

Mexico – 123m

Philippines – 104m

Ethiopia – 94m

Egypt – 93m

Vietnam – 92m

Germany – 82m

DR Congo – 82m

Iran – 80m

Turkey 79m

Thailand 68m

Now, let’s deduct the countries that already have mature investment migration markets:

China – 1.39bn

India – 1.32bn

United States – 325m

Indonesia – 261m

Brazil – 207m

Pakistan – 207m

Nigeria – 193m

Bangladesh – 163m

Russia – 146m

Japan – 126m

Mexico – 123m

Philippines – 104m

Ethiopia – 94m

Egypt – 93m

Vietnam – 92m

Germany – 82m

DR Congo – 82m

Iran – 80m

Turkey 79m

Thailand 68m

Next, let’s cut the ones that don’t have considerable travel restrictions, i.e. countries that have visa-free travel to Schengen:

China – 1.39bn

India – 1.32bn

United States – 325m

Indonesia – 261m

Brazil – 207m

Pakistan – 207m

Nigeria – 193m

Bangladesh – 163m

Russia – 146m

Japan – 126m

Mexico – 123m

Philippines – 104m

Ethiopia – 94m

Egypt – 93m

Vietnam – 92m

Germany – 82m

DR Congo – 82m

Iran – 80m

Turkey 79m

Thailand 68m

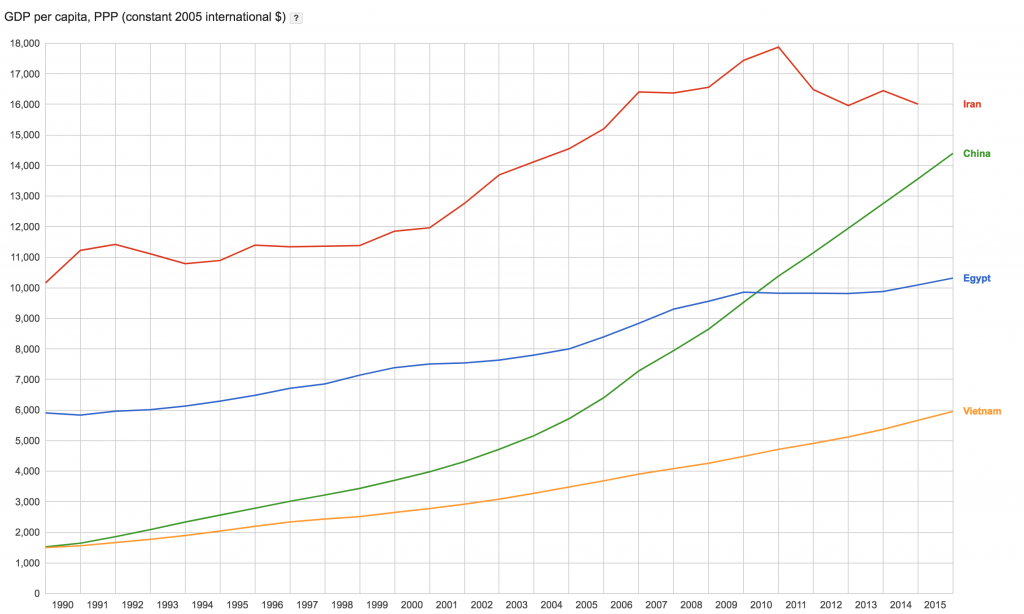

13 countries left. Let’s cut the countries that aren’t yet rich enough to have a high concentration of HNWIs (setting the bar at US$6,000 GDP per capita, in purchasing power terms):

China – 1.39bn

India – 1.32bn

United States – 325m

Indonesia – 261m

Brazil – 207m

Pakistan – 207m (GDP(PPP) per capita is US$4,900)

Nigeria – 193m

Bangladesh – 163m (GDP(PPP) per capita is US$3,581)

Russia – 146m

Japan – 126m

Mexico – 123m

Philippines – 104m

Ethiopia – 94m (GDP(PPP) per capita is US$1,735)

Egypt – 93m

Vietnam – 92m

Germany – 82m

DR Congo – 82m (GDP(PPP) per capita is US$803)

Iran – 80m

Turkey 79m

Thailand 68m

11 countries down, 9 to go. Among the chief motivating factors for investment migration clients is a concern for the safety of their assets due to a lack of respect for property rights, indoctrinating and propagandizing educational systems, as well as the lack of individual rights and personal liberty and so on. In a word; freedom. The less you have of it in a country, the more you want to leave.

We’ll use the Freedom in the World Index to determine which countries to cut from the list. The Freedom in the World Index classifies countries as free, partly free or not free, based on the level of civil liberties and political rights.

Let’s remove the countries classified as free and partly free, and keep the ones listed as not free:

China – 1.39bn

India – 1.32bn (free)

United States – 325m

Indonesia – 261m (free)

Brazil – 207m

Pakistan – 207m

Nigeria – 193m (partly free)

Bangladesh – 163m

Russia – 146m

Japan – 126m

Mexico – 123m

Philippines – 104m (partly free)

Ethiopia – 94m

Egypt – 93m

Vietnam – 92m

Germany – 82m

DR Congo – 82m

Iran – 80m

Turkey 79m (partly free)

Thailand 68m (partly free)

3 countries left, now we’re getting somewhere. Since we’re trying to figure out where the biggest investment migration markets will emerge in the future, let’s look at their projected population and GDP figures five years hence:

Egypt – 100m – US$16,813

Vietnam – 100m – US$9,102

Iran – 88m – US$24,634

All three of these countries are excellent candidates for the next big investment migration market, but we want to find out which is the single best prospect, which means that this analysis will have to move from science to art, from rigid analysis to qualitative conjecture. Let’s take a closer look at all three:

Iran:

Iran is not a poor country. Its GDP per capita, in PPP terms, is on par with countries like Argentina and Montenegro. But Iranians face extreme difficulties in terms of getting their money out. The country has tremendous pent-up demand for second passports and residence permits, but these products are far less accessible to Iranians than to other nationalities because of political sanctions and banking restrictions, as well as the listing of Iranian nationality as restricted in many popular investment migration destinations.

This is not to say that it is impossible for Iranians to obtain second citizenships or residence permits – there are ways around it, such as residing for a long enough time in a third country – merely that the obstacles placed in their way causes the stream of potential clients from Iran to be much lighter than it ordinarily would be.

Iran, while conditions could change suddenly with the lifting of sanctions, is not the prime candidate.

Egypt

Egypt has plenty of HNWIs who have no shortage of reasons for wanting to get out. Political turmoil, government repression and a non-negligible level of terrorist threats plague the country.

But the mother tongue of most Egyptians is Arabic, and virtually everyone in the country’s economic elite speak English as well, which means they have easy access to information and services from companies based in Dubai, the Middle East’s investment migration hub. They can easily travel to the UAE or Istanbul for a consultation, or pick up the phone and speak directly to a client advisor in London or Montreal. I suppose firms could open offices in Cairo, but they could get virtually the same results with a network of introducers.

Egypt is a tremendous market, but by its connectedness to existing markets through culture, language and geography, it’s already covered and catered to.

That’s not the case with the final country on the list.

Vietnam

My money is on Vietnam.

While many in the younger generations speak English, finding someone in the above-40 bracket with command of any language other than Ting Viet is more the exception than the rule. While Arabic is a lingua franca and also a mother tongue throughout large swaths of the Middle East, only the Vietnamese speak Vietnamese.

Egyptians can travel to Dubai for a consultation in Arabic or English, but the Vietnamese won’t travel to Shanghai for the same. No, they need the information and consultants to come to them, in their own language.

It’s got nearly 100 million people, and it’s economy is among the fastest growing in the world, regularly posting GDP-expansions of 6-8% a year.

I think you can predict much of the trajectory of the Vietnamese investment migration market simply by looking at what’s taken place in China over the last few decades, because these two countries have so much in common politically and economically:

- They are both former communist countries (still communist in name) that have opened up gradually to become market-based.

- They are both experiencing decades-long trends of rapid economic growth as a result of economic liberalization.

- They have very limited mobility.

- They both have well established diaspora networks in Western countries and a cultural propensity for emigration.

- They both have very limited political freedoms and property rights.

- China introduced their Reform and Opening Up policy in 1979, Vietnam the Doi Moi reforms in 1986.

Vietnam, in a sense, is China 15 years ago and on one 15th the scale, and is following an analogous path to prosperity. The pattern is the same:

- Step one: Introduce communism and suffer for three decades

- Step two: Realize that communism was a terrible idea

- Step three: Think about how you can improve the situation in your country without admitting you were wrong or relinquishing power.

- Step four: Introduce market liberalization policies and refer to them as “Socialism with (insert demonym here) characteristics” .

- Step five: Experience a multi-decade economic boom but remain politically authoritarian

- Step six: Congratulate yourself on the marvelous achievements of socialism

Because of the commonalities in culture and history, as well as the relative geographical proximity, if Chinese investment migration firms had the appetite for entering the Vietnamese market, they’d have a leg up on their Western counterparts.

As of yet, however, it’s still open season.

Christian Henrik Nesheim is the founder and editor of Investment Migration Insider, the #1 magazine – online or offline – for residency and citizenship by investment. He is an internationally recognized expert, speaker, documentary producer, and writer on the subject of investment migration, whose work is cited in the Economist, Bloomberg, Fortune, Forbes, Newsweek, and Business Insider. Norwegian by birth, Christian has spent the last 16 years in the United States, China, Spain, and Portugal.