The Many Parallels of CBI and Maritime Flags of Convenience

Due Process

With Michael Krakat

Legal Scholar Michael B. Krakat observes investment migration through the lens of international, constitutional, and administrative law.

Water always finds a way. The same is true for people and commerce. The ancient human urge to migrate or to conduct trade across borders follow the rules of water and path of least resistance. Citizenship by Investment (‘CBI’) programs and their counterparts, the discretionary provisions of some states (Citizenship by Discretion, ‘CBD’), claim a high watermark of personal freedom and global mobility for those who can afford to pay. The factors for admission are here virtually channelled into that of price, providing a flow of revenue for the citizenship-selling state.

It may then come as no surprise that CBI and maritime ‘flags of convenience’ have quite a few things in common, beyond sharing the commercial realities of a globalized and deeply interconnected world. Overcoming the burdens of geography and time is an interesting feature in both maritime- and civic versions of the notion of ‘convenience’.

Abstractions exist in both areas, for instance in light of the waived (assumed, exempted, or fictitious) naturalization requirement of CBI at citizenship law when compared to the system of maritime ‘flags of convenience’ registration and operation and with multiple areas of conceptual overlap.

How flags of convenience work

In the maritime world of commercial cargo-shipping, where beneficial ownership and control of a vessel is found to lie elsewhere than in the country of the flag the vessel is flying, the vessel is considered as flying a so-called ‘flag of convenience’.

It is quite common for flag registries to be managed in a different country than the one it hails from. Liberia’s is administered by a US company in Virginia, outside Washington D.C., the Comoros registry is managed from Bulgaria, landlocked Mongolia’s registry is based in Singapore, and Vanuatu has its base in New York.

The unusual geography of the registry system poses challenges, including to security, such as protection against piracy. There are often also large discrepancies between states in which the actual ship owners are based and the flag states that exercise the regulatory control over much of the world’s fleet.

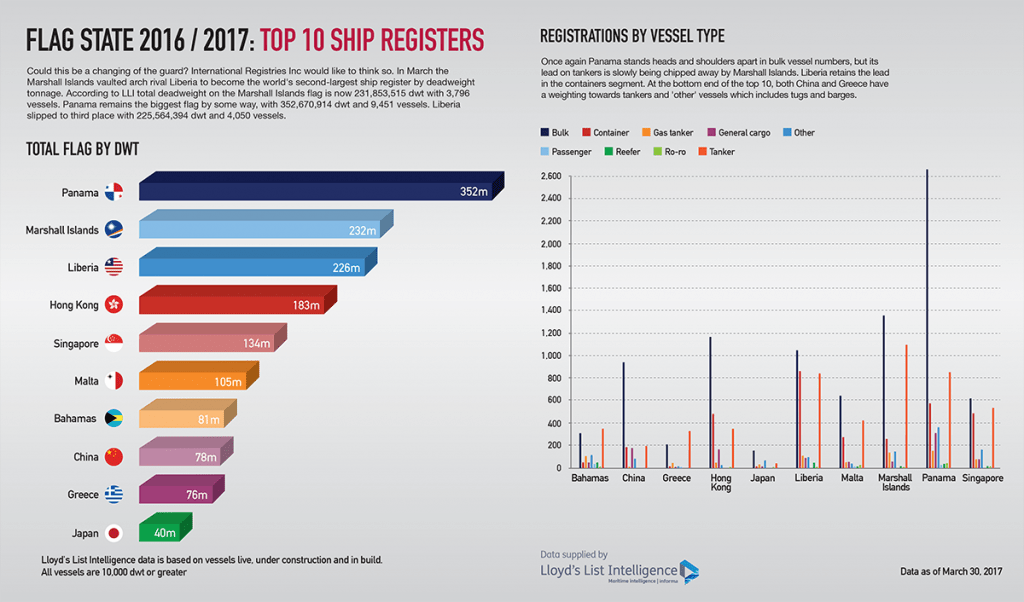

Shipowning states benefitting from flags of convenience include Greece, Japan, China, Germany, Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, the USA, Norway, and Bermuda. In contrast, most commonly flown flags are actually those of Panama, the Marshall Islands, Liberia, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malta, China, Bahamas, Greece, and Japan, often with proven reputation and a presence in every major port, making these flags quite literally convenient.

However, the term ‘flag (or passports) of convenience’ is used by critics of the practice to showcase the abstractions and missing genuineness between the dimensions of ownership, revenue, geography, and actual control and underscore that this abstract, transactional nature is mainly aimed at regulatory avoidance.

Shipowners choose maritime flags of convenience of a flag state for a range of commercial and other reasons, including quality of service and taxation.

While international law specifies that the country whose flag a vessel flies is responsible for controlling its activities, certain states operate what is known as ‘open registries’, allowing foreign vessels to fly their flag for a relatively small fee (relative to the possible substantive gains flowing from the fee).

These selling states may then effectively be left with little or no control by the state over that vessel’s actions or inactions. In other words, flags of convenience also allow vessels to avoid government regulation and to cut operational costs. Countries may be unable or unwilling to monitor and control vessels flying their flag. This could lead to illegal vessel operations, such as pirate fishing to avoid fisheries regulations, poor working conditions, wage dumping, and lack of overall control. For the same reasons, shipowners also change the flags of their vessels, if only shortly before the final voyage to the shipbreaking yard.

The issues are replicated to some extent also in the airline industry. The International Transport Workers Federation (‘ITF’) is campaigning against Flags of Convenience. Again, the problem seem deregulation, abstractions between gains and responsibilities, leading to workers seen as commodities.

After signing up to a flag, the laws of that flag state are conferred to the vessel, tying the vessel to that jurisdiction. International standards (such as conferred through maritime treaties) include rules set by the UN’s shipping agency, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) as to the construction, design, equipment, survey, manning and certification of vessels.

Genuine links

A ‘genuine link’ has been enunciated between the Flag State and the owners of vessels, as required by Article 91 of United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) ‘Nationality of ships’. The article reads as follows:

(1) Every State shall fix the conditions for the grant of its nationality to ships, for the registration of ships in its territory, and for the right to fly its flag. Ships have the nationality of the State whose flag they are entitled to fly. There must exist a genuine link between the State and the ship.

(2) Every State shall issue to ships to which it has granted the right to fly its flag documents to that effect.

That link, however, is not to be misunderstood as a general requirement tying ships to states. In the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea case, The M/V “SAIGA” (No. 2) Case (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines v. Guinea), at para 83 in the tribunal’s findings, the following was said:

“The conclusion of the Tribunal is that the purpose of the provisions of the Convention [referring to UNCLOS] on the need for a genuine link between a ship and its flag State is to secure more effective implementation of the duties of the flag State, and not to establish criteria by reference to which the validity of the registration of ships in a flag State may be challenged by other States.”

In other words, any genuine link for ships is about the duties of the state to look after its vessels, such as matters of safety at sea, not in regards to the system of registration at large. This is somewhat akin to the Nottebohm Case (Liechtenstein v Guatemala) Second Phase, 6 April 1955 before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), in effect concerning an early form of CBI ‘cash-for-passports’, a case of direct naturalization in exchange for payment.

While contentious, the case does also not confer any general international law rule vis-à-vis the community of states as to any overall requirement for a genuine connection between citizens and states. The case is rather to be read in its own limited (and highly politicised) circumstances and before the backdrop of a history of conflicting nationalities in the area of international claims and diplomatic protection.

Problems in governance and oversight

What then precisely constitutes a “genuine link” in maritime law is contentious, presenting a challenge in the life of maritime authorities, such as in the areas of worker’s conditions and illegal fishing.

Again, Flag States – the countries that issue the flags that all maritime vessels are required to fly – are responsible for enforcing a range of international rules and standards against vessels listed in their registry, including ship standards, working conditions. While the flag of a vessel shows its nationality, it does not necessarily identify the nationality of the vessel’s owners – making the enforcement of laws very problematic.

Effective monitoring by Flag States requires good infrastructure and communication between ship registries, the government and other regulatory bodies. This can be a problem, say for example, for landlocked nations of Mongolia and Bolivia, both operating open registries and are being considered flag of convenience states. Their distance from the sea and lack of coastlines make the practicality and intent of either country to carry out inspections questionable.

The issue is further complicated by the fact that some open ship registries are run by private companies based in other countries. It appears that private companies actively approach developing countries with the proposal to set up an open registry, and many operate on a commission basis. To cut the deal, there may be an incentive to make registration an overly simple, at times perhaps meaningless process for potential clients. Poor communication between government and company has been reported, with governments often not being supplied with up-to-date lists of the vessels that are flying their flag.

CBI as passports of convenience?

For the keen reader of this forum, some of the above may ring a bell, with shared concerns that in both areas of maritime- and passport flag of convenience. Issues for CBI may include the areas of potential for loss of control in regulation such as in the delicate areas concerning the nature of the passport purchaser and questions of due diligence, a race to the bottom in price, standards or rules of citizenship conferral, subjection to market logic especially where the majority of a state’s revenue comes from CBI, price dumping and competition affecting citizenship as the inner sanctum of sovereignty, effective dominance by third states granting or refusing visa free entry status into their territories, the effective loss of control to selling agents or broadly speaking, the area of taxation, to name a few.

Panama

Both systems of flags and passports of convenience have been criticised because of a potential for regulatory avoidance and loss. At least the passport programs have shown significant improvements especially in the past decade.

It is in states such as Panama where both passports and flags appear to meet. Just as other maritime flag of convenience countries, Panama is a major player attracting shipowners to its flag. In the process, these countries often refer to common and proven standards, if only to stay competitive. The flag of Panama combines approximately 23% of the world’s fleet, which makes many more maritime vessels than the less than 4 Million citizens and residents of Panama.

Panama boasts with a complete tax exemption on all revenue from international maritime commerce of merchant ships so registered, a 20% discount for multiple vessel registration, as well as tax exemption on capital gains from sale of vessels. There is no need for physical presence for registrations and other dealings.

At the same token, while Panamanian citizenship is not directly possible absent residency of at least 5 years, the country has its own manifold array of rather inclusive permanent residency RBI programs. These include ‘middle-income options’ for citizens from a list of ‘friendly nations’, but also other venues to anyone with larger investments, with certain professional skills need, for retirees as well as includes purpose bound projects such as re-forestation.

Panama then is an example for RBI programs to be versatile, evolving and growing more inclusive, allowing a broader clientele to engage with RCBI. It indicates a possible, perhaps likely future development of RCBI programs for the industry, providing hope for upward global mobility for a broader spectrum of passport purchasers.

Michael B. Krakat is a lecturer and coordinator for comparative Public law – International, Constitutional and Administrative Law – at the University of the South Pacific at Vanuatu and Fiji campuses. Michael is also a researcher at Bond University – Queensland – and Solicitor at the Queensland Supreme- and the High Court of Australia. He also is an academic member of the Investment Migration Council. He can be contacted at michael.krakat@usp.ac.fj.