How to Ensure Fair and Effective Due Diligence on Stateless Applicants

Fabienne de Blois

London

If the UK’s Windrush scandal highlighted the complexities people can experience when proving their residency and nationality rights, often owing to contextual factors outside of their control, it was neither the first nor last reminder for many across the world.

We see parallels every day when assessing the identity and source of wealth of individuals who, for a wide variety of reasons, have no citizenship rights, or who, in other words, are stateless.

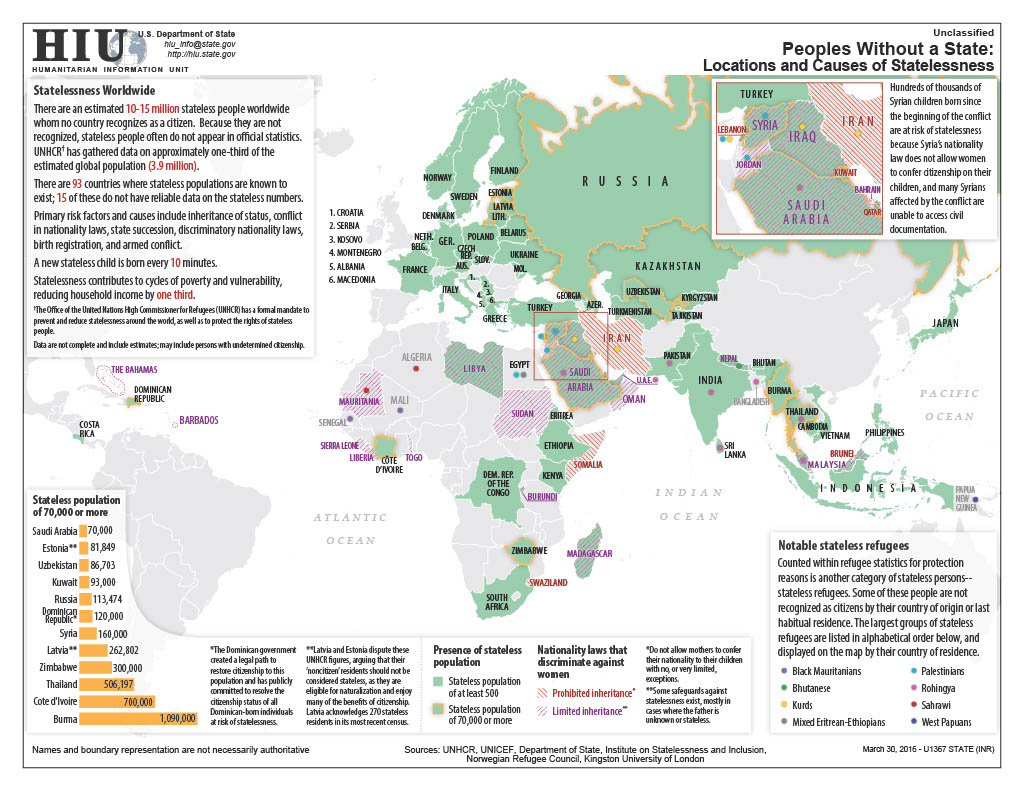

Statelessness impacts a wide range of individuals, from those who have never had access to citizenship rights or the documents to prove their entitlement to them, to those caught between borders at a key period in time, such as when the borders were first delineated and nationality processes and laws were formalised.

Statelessness often also stems from nationality requirements being tightened, as in 2019, when amendments to Indian citizenship laws saw two million people lose their right to apply for Indian nationality in the northeastern state of Assam. The creation of new states and the adjustment of the borders of existing ones can also give rise to statelessness, as was seen across Europe with the collapse of the Soviet Union, where some individuals found themselves settled in territory to which they had no citizenship rights in owing to bureaucratic factors or their inability to meet language test requirements.

Some of those who find themselves stateless today chose to renounce one nationality believing they were entitled to another, before finding themselves unable to meet the requirements of that nationality amidst ever-tightening restrictions on nationality laws.

Read also: The Statelessness Dilemma: Legal Responsibility in the Citizenship by Investment Industry

Citizenship-by-investment units in a unique position?

Statelessness impacts people worldwide – including long-term domestic populations in some of the world’s richest states. Where economic conditions are in their favour – specifically in the UAE, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, which all have significant stateless populations and above-average per capita GDPs – stateless individuals have exercised agency in addressing their statelessness through investment in economic citizenship.

This puts citizenship-by-investment programs in the unique position of assessing whether an individual, and sometimes their family unit, should be issued the first passports they have ever held.

Of course, the decision hinges on effective and objective due diligence being possible. And for this to be possible, the assessment must meld the specifics of the case at hand with a nuanced understanding of the contextual factors that gave rise to the Applicant being unable to access citizenship, and the broader environment in which his or her wealth was built.

Many of the steps we take when conducting due diligence on stateless individuals mirror those we take when investigating the identity and source of funds of an individual in the same context who has citizenship rights. That said, stateless individuals often provide different or fewer documents to attest to their identity, and in turn, their vital records can be absent from state-maintained databases of tax, national insurance, and civil records. This is a specific challenge in Arabian Gulf jurisdictions, which do not publish data on their stateless populations, or take public steps to address statelessness, such as through the provision of UN-ratified travel documents.

Not only are travel documents hard to access for stateless individuals in the Arabian Gulf, but many are also unable to obtain Ministry of Interior-issued police or criminal record clearance documents, which attest to their track record living in, and, more critically, from the state’s perspective, permission to travel to and from, their jurisdiction of residency.

Stateless populations in the region also rarely have access to the formal banking system, even in jurisdictions with otherwise high banking penetration. Notwithstanding this, we have seen instances of passports being issued to stateless individuals in the Arabian Gulf for a specific and finite period, typically one or two years, upon application by the holder, and subject to a formal application by the individual outlining their reasons for travel and a rigorous security vetting process by the issuing authority.

Even where a travel document or passport is unavailable to them, many stateless individuals in the Arabian Gulf hold some form of record issued by judicial, health, or commercial authorities. For those born since the 1970s, this may be a birth certificate issued by the health authority that oversaw their home or hospital-based birth, although Ministry of Health recorded births prior to the 1970s were extremely rare in the Gulf – especially in communities at risk of statelessness. Other documents, such as lease contracts ratified by land and real estate authorities, which can sometimes be publicly and independently verified, also list their full names, dates of birth, and, if they have access to one, an internal identity number.

While the civil affairs and judicial documents many stateless individuals in the Arabian Gulf can provide are useful in helping us pinpoint their identity, they come with their own challenges. Documents issued by civil, commercial, health, and judicial authorities, such as those pertaining to custody, marriage, and death, can erroneously list their holder as a national of the issuing jurisdiction. These errors are usually unintentional and owe to assumptions made by the clerk at the issuing authority.

To add to the complexity, we often observe intentional mistranslations of the nationality fields of these documents, which are aimed at offsetting perceived complications but can inadvertently create confusion for document assessors in client units.

After the veracity of the identity information provided in the application has been confirmed through independent inquiries with the issuing bodies of these documents, the due diligence process shifts towards understanding the reason the individual has no access to citizenship rights.

Read also: Vanuatu to Offer Citizenship by Investment to Stateless People – Local Agent Gets Exclusive Deal

Many of our clients come to us for clarity on whether an individual is, in fact, stateless and, as such, whether their inability to provide a passport and police clearance certificate to support their application should be taken at face value. The answer here is never easy, and always rests on our understanding of the contextual factors that give rise to statelessness, as well as assessing the individual’s specific circumstances.

The first clue to the latter question is often found in the documents the individual can provide. While stateless individuals in the Arabian Gulf are referred to in civil society and campaign literature as Bidoon (بدون), meaning without in Arabic, this phrase does not appear on any identity documents they are able to obtain, such as driving licenses and marriage documents. Instead, the term entered in the nationality field in a Ministry of Interior-issued identity document held by a stateless person varies considerably – ranging from a blank field to undefined to a statement declaring the holder a non-national of the issuing state.

Of course, statelessness does not always owe to bureaucratic inefficiencies or ill luck during a border delineation process. Citizenship rights can be intentionally revoked by states through public judicial processes. The grounds for the revocation of citizenship rights can range from serious criminal convictions to charges of sedition.

Over the past decade and a half, the UK has refused to renew the passports of over 400 individuals on a mixture of national security and fraud grounds, with many of these decisions appealed in court. In the years following 2011, which saw the onset of the civilian uprisings and political unrest in the region, Bahrain is reported to have revoked the citizenship of almost 1,000 of its citizens on political grounds and sedition-related charges, also largely through judicial procedures.

These examples reiterate the importance of on-the-ground inquiries in legal circles, which can help us identify the location of, and subsequently retrieve, publicly available court records, many of which are available only in manual format via a specific on-the-ground inquiry to the court in question via a local lawyer.

It also reinforces the importance of incorporating context into the due diligence assessment so that the grounds for the revocation of nationality can be properly understood in the context of prior precedents, and the reputational impact of the revocation can be properly assessed by the authority considering issuing the individual with a new passport.

Once the applicant’s identity and reason for statelessness have been established, the due diligence process pivots towards their source of wealth and the source of funds for the application. Many of the applications from stateless individuals that reach our desk demonstrate that statelessness comes with specific economic and commercial constraints. Most stateless individuals have restricted property ownership and investment rights, and many are unable to access public services and privileges. In turn, property and commercial assets that contribute to their wealth generation are often owned by family members or other close associates who do have citizenship rights.

Given the restricted access many stateless people have to the banking system, assessing source of wealth concerns during the due diligence process often rests on shedding light on their trade-, cash- and virtual currency-based transactions. Where the subject’s financial transactions are not digitally recorded, it becomes even more important to assess the individual’s profile through the lens of trends and risks in the sector in which they operate and to build a balanced picture of how much cash income an individual can realistically be expected to receive from a particular business, given its location, client-base, and the quality and provenance of the products. Within this context, it is critical to understand the size and probity of the business’ client and supplier base, and the modus operandi of the business as perceived by individuals who have real, on-the-ground interactions with it.

A recent case encapsulates the value of this nuance. We were tasked with assessing the source of wealth concern attached to an individual who was born to stateless parents in the Arabian Gulf and who worked as the de-facto manager of a car showroom in the region. In this instance, we were able to reassure our client that the commercial probity of the car sales person was locally perceived to be upstanding, and that he appeared to have built his wealth gradually through genuine cash-based transactions at a well-regarded sales room which he beneficially controlled, albeit for its formal license being in the name of a close relative with citizenship.

Case studies like this help reiterate a caveat that all enhanced due diligence professionals with a track record of working across the world can attest to – the textbook warning signs of money laundering and corruption are starting points, rather than answers. Instead of treating these warning signs as conclusions, we use them to help us identify where we can delve deeper into a case, through human source enquiries and a careful melding of case specifics and contextual understanding.

While a cash-based business operating in a jurisdiction with otherwise high banking penetration, or a subject who beneficially owns an establishment but makes no appearance on corporate records, are text-book indicators of concern, the due diligence process should not stop with their identification.

To push further, it is important to reach out to trusted human source networks – individuals who understand how a business is run, what its supply chains and client base look like – and, critically, the business’ perceived probity and level of activity in the circles it reports to operate in. Only by triangulating information in the public record in this way, can we build a nuanced understanding of the individual’s identity, reason for statelessness and wealth generation trajectory.

Fabienne co-leads the S-RM dedicated investor due diligence practice. She has 12 years of experience researching and managing complex due diligence, business intelligence, and corporate investigations projects for multilateral institutions, global law firms, and leading corporates and is well-versed in the intersection between social, legal and economic dynamics and civil society and public record engagement with issues that present global AML and ABC concerns. Before joining S-RM in 2018, Fabienne worked for two leading corporate intelligence consultancies, and in a research capacity for leading academics researching statelessness and political economy dynamics in the MENA region. Fabienne holds a BA in Arabic and Politics from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London.