Citizenship by Investment And The Right to Be Unremarkable

In 2000, I flew as part of a three-man team to Switzerland to conduct due diligence on a firm seeking venture capital financing. It was a pretty unremarkable and typical corporate trip, except for one quirk:

I had traveled from the UK, where I was living at the time, to Switzerland for a three-day business trip on my Dominican passport. I had found out that, even back then, Dominica had visa-free travel to Switzerland, yet I got held up in immigration for a considerable time. Why? Because whilst everything was correct, the Swiss officials had difficulty believing that someone with a Dominican passport could be coming on a business trip from London and plan to return a couple of days later.

I took no offence. Whilst there were Dominicans living in Switzerland even then, the idea of a transient Dominican businessman living in London seemed difficult to compute, especially as they could barely understand why they couldn’t see the country on a map – nor, indeed, how it was somehow different from the Dominican Republic.

When we try to imagine why someone wants to hold the passport of another nation, I remember this anecdote because the life of so many who travel and want to travel internationally is even more complicated.

Invisibility by investment

Since 2000, Dominica, and the other Eastern Caribbean islands that have citizenship programs, have gained many more visa-free destinations. But even back then, my speck of an island had had a program running for seven years already, one which had thousands of applicants.

The reason Dominica continues to have thousands of applicants each year is the same as that which motivates the endless migration out of the Caribbean today. Caribbean people making a ritual of boasting US, UK, or Canadian citizenship or visas. In travel, being invisible – or, at least, unremarkable – is the goal. No one wants to be pulled aside, to be noticed, to be singled out because of questions arising from their nation’s passport.

Note that I say the passport of their nation. Many good people are stereotyped by their nationality and the passport that they hold. Many people are thankful that a Dominican passport – like a Grenadian, a St Lucian, an Antiguan, or a Kittitian passport – still has a high status, the value of which is immense and growing.

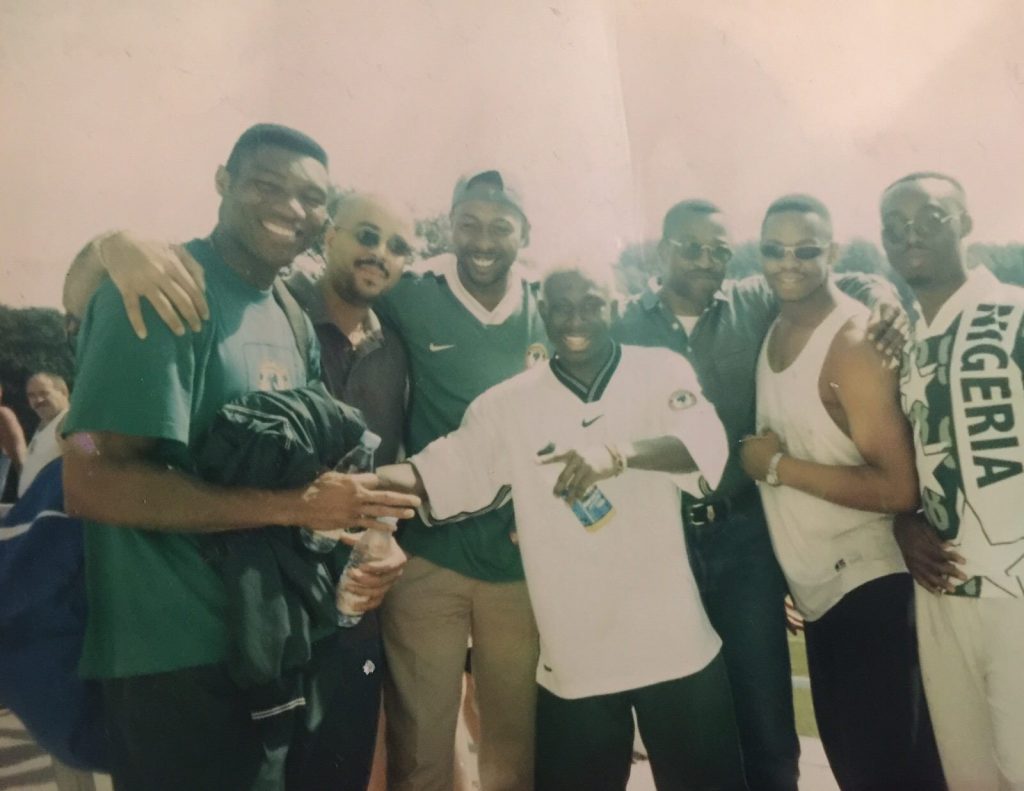

Two years before my Swiss experience, I traveled to France for the 1998 Football World Cup. Again on my Dominica passport, and again from London. This time, though, my travel mates were strictly Nigerian and we followed the Nigerian team because one of my friends was related to their goalkeeper.

The experience of those Nigerians who came from Nigeria and those who came from the UK on British passports differed markedly. Though their backgrounds were no different, the gap between a Nigerian passport and a British passport was enough to bestow upon the groups two starkly different experiences.

My experience was one of invisibility – to a point -because I had been to France on work previously and the immigration officer was busy trying to find out if Dominica was a part of Jamaica (which had qualified for their first-ever World Cup). Once more, the experience served to demonstrate the value of my Dominican passport.

CBI: Born in the Caribbean, raised elsewhere?

Caribbean people were amongst the first to recognize the concept of economic citizenship (i.e., citizenship-seeking motivated by economic circumstances, a broader category than investment migration). Every migration cycle is fueled by economic citizenship, an observation borne out by the number of Caribbean people in the US, Canada, and the UK.

The only fundamental difference between Caribbean people seeking citizenship in North America or the UK and the investor migrants that seek our citizenships is that we seek alternative citizenships primarily to obtain rights to physical presence outside the Caribbean while investor migrants, generally, seek it for the travel freedom. But the reasons are the same; Strictly economic.

Attempts to belittle the importance of what has turned out to be a growth industry for the Caribbean and for the rest of the world, therefore, should be converted into reminding citizens of the Caribbean of the industry’s genesis and value. When our countries are financed by programs we host, we ultimately benefit. Everyone should appreciate that our economies are linked to this industry. We do need to grow our local ownership of the industry, but the benefits – both tapped and untapped – remain vast.

The truth is that we all, to some extent, live in a CBI world. Some of us invest our entire lives to build a presence in countries far away from our birth homes in a bid to secure our families’ future. Others use equity in certain countries, like ours, to gain mobility and financial freedom beyond the limitations of their birth countries.

Investment migration, as a market and as a concept, is worth protecting and strengthening, especially in an ever-changing world in which citizenship and residency options are becoming fiercely competitive platforms.

If we do not take heed, to paraphrase a popular local radio advert, citizenship by investment will be born in the Caribbean and raised elsewhere.

Kenneth Green is an investment migration specialist and a Managing Partner at Advance Global Partners