The Case For Citizenship by Investment Is Never Stronger Than During Times of Crisis

Due Process

With Michael Krakat

Legal Scholar Michael B. Krakat observes investment migration through the lens of international, constitutional, and administrative law.

Where RCBI laws are constitutionally valid, CBI programs, in particular, focus on the transactional, contractual aspects and legal nature of citizenship, and less on the collective political ‘social contract’. This is necessary as CBI laws grant substantive shortcuts or exceptional waivers to otherwise very lengthy naturalization requirements. Critics of CBI often do not address the law but the politics of CBI, addressing the identity side of citizenship, followed by arguments as to commodification, which are, after all, political concerns.

Concerns about the acceptability of CBI go dormant during disasters

These concerns should, in any case, be informed by the underlying goals of such revenue creation. Internal and global acceptability of CBI, even justifications (if such were needed) for the sale of citizenship, then appear to be especially relevant and making a strong case during times of (perpetual) crisis.

During a disaster, concerns as to the acceptability and actual acceptance of CBI by the existing citizenry, as well as the world at large, may remain more or less dormant. It is especially in times of crisis where the sovereign state is seen to act in defending its existential claim to power.

Discussions on the relevance and moral or political acceptability of RCBI should not leave out the reasons as to why a selling state engages with what I have termed the ‘global market for membership entitlements’. Again, this is not to suggest that (R)CBI practice, today, is in need of justification in any given circumstance; rather that circumstances, at any given time, should never be dismissed.

The constitutionality or validity of directly purchased citizenship (or residence status), outside regular naturalization’s temporal or physical-presence requirements, may depend on the legal circumstances of each particular polity engaging in the practice.

Acceptable to whom?

Readers of IMI are all too familiar with how difficult it can be for the CBI market to gain acceptance, both among individuals and institutions, frequently evidenced by the views of the OECD or the EU-Commission, or by the statements and representations about RCBI in the media. But the validity of CBI law does not at all depend on the opinions or sentiments of third parties alone.

More problematic would be cases where most or parts of the existing citizenry fervently disagreed with the programs. This is because citizens, on the one hand, themselves form part of the concept of sovereignty (such as in the form of a popular sovereign), as well as part of the permanent population of a state and, as such, of statehood itself.

Statehood, as enunciated in the Montevideo Convention of 1933 (and earlier in rudiments, by the jurist Georg Jellinek) consists of the following factors that pertain to and, together, make the state:

A permanent population, a defined territory, and a government exercising power, with an added capacity to enter into relations with other states deriving from that power.

Internal acceptance of RCBI is, as such, an important factor.

Likewise, clashes arise where gradations of citizenship or class(es) of citizenship are created, particularly where a polity’s constitution speaks of “one undivided citizenry” (as most, if not all, constitutions do). Here, citizens-by-investment may face effective limitations that other citizens do not, such as the publishing of personal details on a register, the requirement to maintain a property investment, or limitations as to the active engagement in political office or on voting.

CBI may here suffer some internal issues of legitimacy vis-à-vis the existing citizenry. Also, all depending on the particular jurisdiction, it may not always be entirely clear whether citizenships obtained through CBI programs can be revoked (or ‘stripped’) any easier than non-CBI.

See also: The Citizenship-Revocation Policies of 9 CBI-Jurisdictions: What it Takes to get “Kicked Out”

In any case, whether CBI is lawful or not depends first and foremost on the laws of the selling country, not on random dismissals through the pointing at malpractice in other jurisdictions. One bad apple may not make all other apples bad. Any CBI practice is not any more or less legitimate just because it can be compared to others who may engage (or have in the past) engaged in malpractice. Generally, it would appear that the good reputation of RCBI has increased dramatically over time, again, subject to the circumstances of the relevant jurisdiction.

There is of course no ‘equality in the wrong’ and malpractice cannot be justified because another state got away with it. The governance of RCBI is first and foremost an internal obligation of each state running these programs. In addition, global best practice rules of RCBI engagement are emerging, such as the IMC’s Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct, its Disciplinary Rules, or the Anti-Bribery and Corruption Policy, which are of great assistance in this respect.

The logic of crisis

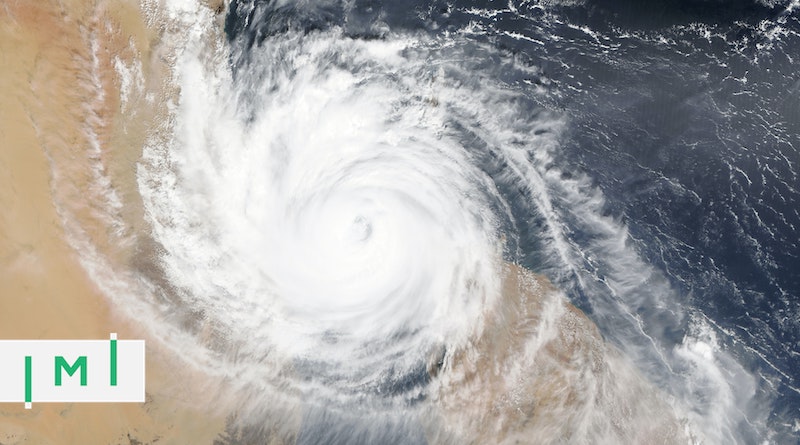

Be it perpetual global pandemics, climate change, economic meltdowns, or any other genre of calamity that a sovereign state might wish to mitigate by tapping unconventional revenue sources: The case for the sale of residence or citizenship is never stronger than in crisis time.

Crisis as justification, because it may be used to reduce as well as enhance our liberties, is a path of argumentation that should be pursued with caution. We also should not let the crisis justify any lowering of standards within RCBI programs. What is suggested here is not that anything goes but that the practice of RCBI, where viewed critically, must be taken into consideration holistically, together with the justifications of our time that, regrettably, seem to be ongoing (take COVID-19).

Many constitutions contain crisis provisions that would allow the introduction of RCBI schemes, the acceptability and justifiability of which are heightened during times of crisis.

Much may depend on the definition of ‘crisis’; most if not all states may be undergoing some form of existential crisis, so to speak, by way of their mere existence. Where proper processes are in place to protect the Rule of Law, the case for RCBI outside crisis is strong but grows even stronger during periods of existential need for revenue through the sale of membership entitlements, that is, of residence or citizenship.

Ideally, to paraphrase Malta’s then-Prime Minister, the Hon. Joseph Muscat, at the 2016 Investment Migration Forum in Geneva, a selling state should engage with RCBI from a position of strength and create the RCBI proceeds for its respective fund in addition to, not in lieu of, a functioning economy.

Michael B. Krakat is a lecturer and coordinator for comparative Public law – International, Constitutional and Administrative Law – at the University of the South Pacific at Vanuatu and Fiji campuses. Michael is also a researcher at Bond University – Queensland – and Solicitor at the Queensland Supreme- and the High Court of Australia. He also is an academic member of the Investment Migration Council. He can be contacted at michael.krakat@usp.ac.fj.