Dr. Antoine Saliba Haig

Valletta

Is your last name Borg, Camilleri, Vella, Farrugia, or Zammit? If so, chances are good you qualify for Maltese (and European Union) citizenship.

Malta’s citizenship laws allow individuals with Maltese heritage to obtain citizenship by descent. The country has opened this route up to third-generation descendants of Maltese citizens, which theoretically means hundreds of thousands of people worldwide may qualify.

This guide provides an overview of the relevant legal framework, historical context, diaspora population, eligibility criteria, and application process.

Legal Basis

The Maltese Citizenship Act (Chapter 188 of the Laws of Malta) governs Maltese citizenship by descent, outlining the criteria and legal framework for acquiring citizenship by descent and other routes such as birth, naturalization, and marriage.

Before Malta’s independence, the Maltese constitution contained most provisions regulating citizenship.

Although Malta established its legal framework on citizenship in 1964 when it achieved independence, recent amendments have significantly augmented its citizenship law.

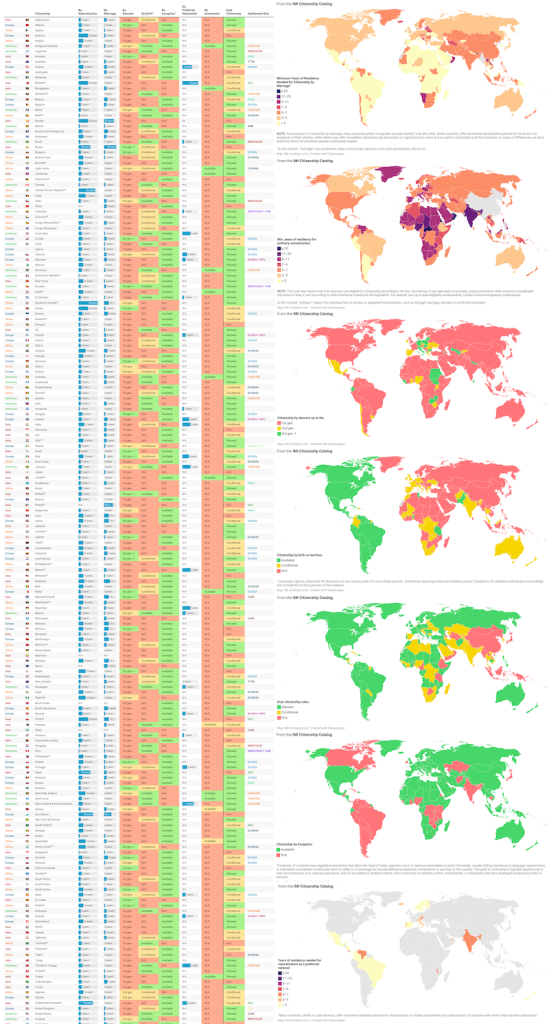

See IMI’s comprehensive list of EU citizenship by descent policies to explore different options across Europe.

These changes allowed Maltese migrants to hold dual citizenship and extended the opportunity for second and later generations to apply for Maltese citizenship.

As Malta completed its accession to the European Union (EU), Maltese citizens automatically became EU citizens.

Maltese Immigration History

More Maltese descendants reside abroad than on the Maltese islands. The largest communities are in Australia, the UK, Canada, and the United States.

Mass emigration from Malta started during the 19th century when many Maltese nationals migrated to Egypt, particularly Cairo and Alexandria, for work.

Rising opportunities from British commercial and military activities in the region attracted Maltese craftsmen to Egypt and Tunisia.

The Maltese communities in North Africa have largely dwindled, as many members relocated to countries like France, the United Kingdom, or Australia following the rise of independence movements in the region.

After the First World War, Malta experienced economic difficulties due to the downturn of its dockyard industry, resulting in widespread emigration.

The post-war economic slump compelled many Maltese to seek job opportunities overseas. During the inter-war period, around 15,000 Maltese emigrated to major industrial cities in the US, and Detroit was a primary destination.

Large-scale emigration occurred after World War II. Unlike earlier migrations to Mediterranean destinations like Egypt, Algeria, and Tunisia, these later migrants favored more distant, English-speaking countries such as Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom.

Estimates suggest that almost 30% of the population left Malta for better opportunities abroad. Even after Malta gained independence in 1964, emigration continued due to economic challenges. By the late 20th century, Malta's economy began to improve, slowing the emigration rate.

Since Malta joined the European Union in 2004 and experienced economic growth, Maltese nationals have been returning home or relocating to other EU member states for work.

Today, Malta's diaspora spans several continents, boasting significant communities that maintain strong cultural ties with their homeland and preserve Maltese traditions, language, and identity abroad.

How to Qualify for Maltese Citizenship by Descent

When Malta gained independence on September 21, 1964, the Independence Constitution outlined the criteria for automatic entitlement to Maltese citizenship, whether by birth or descent, and the process for registration as a citizen.

In 1965, the Maltese Citizenship Act expanded upon these constitutional provisions. In 2000, lawmakers removed the regulations regarding citizenship from the constitution and consolidated them into the Maltese Citizenship Act (Cap 188).

Shift from Ius Soli to Ius Sanguinis

The term ius soli refers to the principle of granting citizenship based on birth within a country's territory, while ius sanguinis grants citizenship based on the nationality of one or both parents, regardless of the child's place of birth.

Persons born in Malta before September 21, 1964, whose one parent was born in Malta automatically became Maltese citizens.

For a brief period, Malta adopted the ius soli principle, where persons born in Malta between September 21, 1964, and July 31, 1989, obtained Maltese citizenship automatically, provided that their father did not enjoy diplomatic immunity in Malta.

This rule changed on August 1, 1989, and individuals became Maltese by birth if they were born in or outside of Malta and, at the time of their birth, their father or mother were Maltese citizens.

See all routes to citizenship in all 195 countries with IMI's Citizenship Catalog

The Concept of Dual and Multiple Citizenship

At the time of Malta's independence, Maltese citizenship law did not allow dual citizenship, except for minor children, who, to retain their Maltese citizenship, had to renounce their foreign citizenship between their 18th and 19th birthdays.

Adults with other foreign citizenship had to renounce it before September 21, 1967. Citizens of Malta who voluntarily acquired a second citizenship automatically lost their Maltese citizenship.

The concept of dual nationality first came into Maltese legislation in 1989, but it was only open to those who had emigrated. Persons had to be born in Malta, emigrated to another country of which they became citizens, and spend at least six years living in that country.

In 2000, lawmakers made essential changes, fully introducing dual and multiple citizenship.

From February 10, 2000, a Maltese citizen could obtain and keep both their foreign citizenship and Maltese citizenship.

Foreign nationals who obtain Maltese citizenship through registration or naturalization can also retain both Maltese and their original nationality, subject to their home country's laws permitting dual citizenship.

Maltese Citizenship by Registration

The government introduced further amendments in 2007, expanding the scope of the Maltese Citizenship Act, allowing second and subsequent generations of Maltese descendants born abroad to obtain Maltese citizenship through registration.

A descendant in the direct line of an ascendant born in Malta of a parent likewise born in Malta can apply for citizenship through registration.

Article 3(5) of the Maltese Citizenship Act imposes one limitation.

It states that where any of the parents of a person applying for citizenship by registration was alive on August 1, 2007, and such parent is also a descendant in the direct line, that person is not entitled to register as a Maltese citizen unless the relevant parent had also acquired Maltese citizenship.

If, however, any such parent had died before August 1, 2010, and would have been eligible to acquire citizenship, Malta considers that he or she had acquired Maltese citizenship.

This consideration does not apply to a parent who dies after July 31, 2010, without having applied to register as a Maltese citizen.

The specific application process involves submitting various documents, such as birth certificates, marriage certificates, and proof of Maltese lineage.

Processing times may vary depending on the individual case and the volume of applications the government has on hand.

"Forbidden"