10 Reasons Indian HNWIs Have Been Slow to Embrace Investment Migration

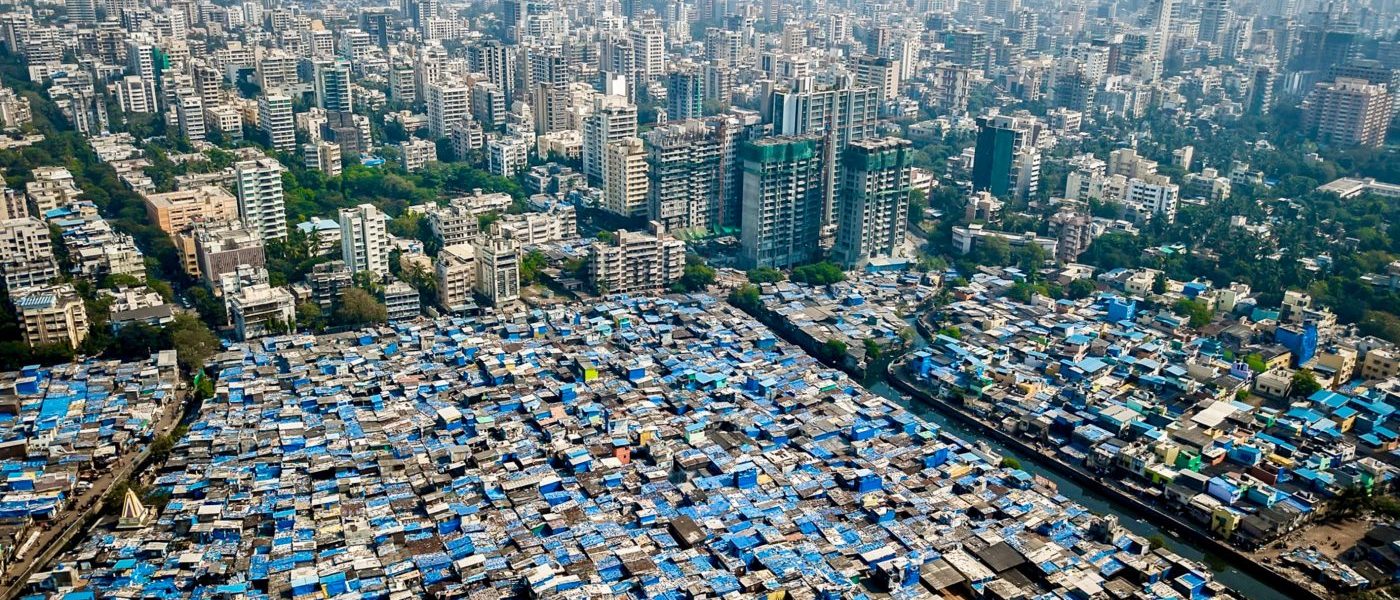

On the surface, India’s market for investment migration has the same fundamental conditions as China; a population of some 1.3 billion, a passport with limited mobility, a large number of HNWIs, and plenty of push factors like pollution, restrictions on individual liberty, and lack of educational opportunities. But look closer, and you’ll find that India has many more obstacles – mainly cultural – that have prevented the investment migration market from flourishing to the same degree that it has in China.

We’ll look at each of these limiting factors in turn but, first, some background.

Read also: Basic Dos and Don’ts for Entering the Indian Investment Migration Market – By Prashant Ajmera

A brief history of Indian emigration

Migration from India to other countries around the world started in earnest more than 100 years ago. Back then, the migrants were mostly laborers recruited to work on sugar plantations in the Caribbean islands and Mauritius, railroads in Canada, and as industrial and domestic workers in South Africa, Malaysia, and Indonesia. During this period, only people with meager means thought of migrating abroad in order to sustain their families.

After India’s independence from British rule in 1947, however, this labor migration decreased dramatically. The post-independence period saw Indians leaving the country for a very different reason; that of obtaining higher education and, thereafter, settling abroad. During this period, foreign migration became a symbol of social status, and obtaining a foreign education and living abroad become aspirations that most Indians nurtured but which very few of them could afford.

The most favored destinations were the USA and the UK. Qualified Indians pursued higher studies in these countries and then settled into lucrative jobs. Doctors, engineers,

In the mid-seventies, the Gulf countries – notably the UAE, Oman, and Kuwait – were growing exponentially thanks to petrodollars. Need for advanced infrastructure development, high-tech facilities and world-class standards of living generated demand for a huge labor force; qualified professionals as well as

This unprecedented growth prompted a second wave of workforce migration from India to the Middle Eastern countries. Presently the Indian diaspora is the most populous expat community in the Middle East.

This era was fraught with recruitment scams and fraudsters cheating ignorant workers with false promises of a highly paid job and a better life in exchange for huge amounts of money. Because of this, in the year 1983, the Indian government passed the Emigration Act to regulate agents recruiting manpower from India mainly to Middle Eastern countries.

In 1993, Canada introduced skilled migration. It was a highly streamlined process, paving the way for systematic skilled worker migration from India to Canada. Eventually, Australia, New Zealand,

During the late 80s and all throughout the 90s, the growing IT industries and start-ups in Western countries and the Y2K problem attracted a large pool of IT professionals from India.

These professionals, who received mediocre salaries in India, were highly paid by foreign companies. Good money, cushy jobs and a high standard of living eventually prompted them to settle down with their families in these countries. This was a period of ‘brain-drain’ for India.

All this migration created a very deep stigma in the upper echelons of Indian society who began to regard migration as something undertaken by economically deprived people only. According to them, migration was for people with lesser means so that they could earn more abroad.

Interestingly, many of these wealthy people who looked down on migration had themselves migrated from villages to cities within India in search of wealth and a better life during their youth.

This gives us a brief background as to how migration evolved in India. Though we are at the threshold of the year 2020, Indian HNWIs are quite slow in making a decision to immigrate abroad. Residency and citizenship by i

The 10 main reasons Indian HNWIs have been slow to embrace residence and citizenship by investment

1.The mind-set that immigration is only for the economically deprived

As mentioned, not only HNWIs but a majority of Indians harbor a deeply rooted belief that immigration is only for the economically deprived. In my 27 years of practice, I have come across a great number of people who come to consult me and start the conversation with these lines: “We are very well-to-do and not interested in moving abroad. But I am doing this (immigrating) for the sake of my children’s education and future”.

Most of these people are senior executives of multinationals, owners of SMEs, or wealthy businesspersons. They enjoy a high standard of living and their net worth is in the millions of dollars.

2. Stable democracy and

India became independent in 1947, but today it is the world’s largest democracy. Though home to several religions, languages, and classes of people, it is a relatively safe country in which to live. The law and order situation is reasonably good and, though there may be unrest in a few pockets across the nation from time to time, there is peace and safety most of the time.

Additionally, the Indian economy is getting stronger by the day. These factors discourage many Indian HNWIs from moving abroad unlike their counterparts in countries such as China and Russia.

3. Lack of Knowledge among HNWI advisors

In the past three or four years, we have seen a growing interest among HNWIs in various residency and citizenship programs. Unfortunately, their usual financial advisors like chartered accountants, wealth managers, and lawyers have little-to-no knowledge about any of these programs.

Many HNWIs are even skeptical about the existence and authenticity of these programs and wonder if it’s an international scam. I recently met the senior partner of large and reputed client advisory firm who had no clue about investment migration and was surprised that it can be a highly beneficial investment opportunity for HNWIs.

4. Lack of familiarity with investing abroad

Until recently, Indian banks and concerned government agencies had very strict and conservative rules in place that deterred Indian professionals and businesspersons from remitting money outside of India. Hence, the entire concept of investing abroad is quite novel for most Indian HNWIs. Now, with more favorable regulations, HNWIs are showing a willingness to venture into the unknown RCBI territory.

5. Lack of knowledge about residence and citizenship by investment programs

Lack of basic knowledge about RCBI and its benefits makes HNWIs less trusting of such programs. With no one to assist them and clear their doubts, they are confused regarding the value of investment migration programs as a safe and rewarding investment.

6. Multiple obstacles related to cash transactions and liquidity

With the exception of large metros, most real estate and large financial transactions in India are carried out in a split manner to avoid taxation – around 30-35% of the real estate price is paid through bank transfer whereas 65-70% of the transaction is by cash. This creates a perennial liquidity issue for Indians who often have to struggle to show that they have the necessary financial capacity to invest abroad through official banking channels.

7. Difficulty with documents and other legalities

India does not have a nationwide social security system. Additionally, there is no credit rating system for individuals and corporates. Business is commonly conducted based on personal references. Drawing up detailed agreements and legal documents and hiring professionals to guide through the entire process is still not a common practice.

In contrast, RCBI programs involve a plethora of legal documents and other formalities that can be completed only with the help of qualified and knowledgeable professionals. Many Indian HNWIs are flummoxed when they realize how many supporting documents they need to submit with their application and the other legalities they need to complete. Gathering and compiling relevant documents is an uphill task for most of them.

8. Negative perceptions of investment migration

Indians often assume that if a wealthy person has applied for immigration, he/she must be doing so for all the wrong reasons. In recent times, several UHNWIs have fled the country in order to escape prosecution and possible jail time and taken refuge in foreign jurisdictions through investment migration programs.

The Indian media has exploited these stories extensively to generate negativity about RCBI programs, highlighting how HNWIs are taking undue advantage of these programs to avoid persecution at home and live a comfortable life elsewhere. All this undue attention has made

9. Lack of trust

Non-payment of invoices and private investment is widespread in India. HNWIs, as consequence, generally don’t trust foreign developers and their projects. This lack of trust – combined with the Indian mentality of investing in a foreign project where other Indians, preferably friends or relatives, are involved – has proved to be a great disadvantage for foreign developers and their projects.

There are several examples wherein many Indian-origin investors from the USA have been successful in raising millions of dollars for their debut EB-5 projects whereas some highly reputed EB-5 regional

10. The Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA):

FEMA and the regulations therein make it difficult for Indians to transfer or remit payment outside of India. Violating the law was a criminal offense in bygone years but is now just a civil offense that can result in up to 300% penalty if money is remitted without duly following the law.

The need of the hour is to work hard collectively to educate Indian HNWIs and the professionals serving them about how RCBI programs are not only about immigrating to a foreign country but much more.

Though the Indian market is slow to pick up, it is my firm belief that in the next few years, India will be a significant player in the global investment migration market.

Image credit: Johnny Miller/Unequal Scenes

Prashant Ajmera is an India-based immigration attorney with more than 25 years of experience in the field of investment migration. He is the principal of Ajmera Law.