Passports: Once a Large Piece of Paper, Today a High-Tech Booklet – And a Commodity

Tom Topol

Passport history expert and author

The word passport was not in existence before the 15th century and originated from the French word “passeport” – passer (to pass) a (sea)port.

Hi, my name is Tom Topol, a passport history expert for almost 20 years and author of the book Let Pass or Die. My frequent business trips in a global biotech position have given me the benefit of traveling the world. In Kyoto, Japan, I found and bought my first old passport: A beautiful travel document from the 1930s Japanese Empire, showing a young Japanese girl in her Kimono. Since then, passport history, research, and collecting old passports have become my passion. Today, I own a collection of about 700 old travel documents; the oldest is from 1646.

Passport booklets as we know them today have only existed for roughly 150 years. Passport photos have been in use only since 1915.

Identification papers, until the 14th-century, were a privilege; only from the 15th-century did passports become somehow obligatory. For the first time, issued to soldiers, especially mercenaries who had returned from war and for whom such a document served as a letter of dismissal.

A Letter of Recommendation

Who was traveling in the 16th century? Before tourism (i.e., traveling for pleasure, without a real purpose) was common, only the powerful and determined would take to the roads and seas – at least until 1841, when Thomas Cook invented package tourism.

A typical 16th-century passport was a handwritten document on paper, issued by a local lord, administration, or a senior military officer. The primary purpose of the passport was not to identify the bearer but to act as a ‘letter of recommendation,’ a safe-conduct to support the traveler on their journey when entering or crossing foreign soil. Issuing passports was not an exclusive right of the state either in the 16th-century.

Once an assistant had written up a ‘passport,’ his master would sign and seal the document. The signature and wax seal served as a sign of the issuer’s authority and as a security measure to avoid falsification. As passports had a purely functional character back then, more detailed descriptions of the bearers got added to the early modern passport, which initially was no more than a sealed certificate for a person named by name.

Physical characteristics, such as size, hair and skin tone, conspicuous scars, or moles migrated from early passports to modern versions. But this was only true for the poor; wealthy and high-ranking travelers in Europe were exempt from describing their bodies and registering their ‘special characteristics.’ Their passports contained only names, and the fewer personal details they included, the more effective they were. In his memoirs from the 18th century, Casanova wrote that “a passport gained one respect abroad.”

Most liberal countries in Western and Central Europe abolished a passport for foreign travel in the last third of the 19th century due to the nostalgic idea of traveling across Europe without visas and identity papers. In 1888, English and French railway companies promoted the luxurious journey on the Orient Express from London to Constantinople. There was no need to change trains or present a passport, and wealthy people specifically – first-class passengers – were exempt from passport requirements and compulsory checks.

See also: The Passport Throughout History – The Evolution of a Document

At the end of the 19th century, something that came up was the vital link between passport and nationality. From the 17th until well into the 19th century, many people traveled with passports issued by their destination country and not by their country of origin: Any official document was proof of identity. By 1914, however, passport and citizenship were closely linked. The passport was thus not only a certificate of identity but also a certificate of affiliation.

Passport Design in History

Until the end of the 19th century, no one was seriously thinking about the design of passports. A passport had a purely functional character. However, as the function of passports changed, new requirements emerged regarding durability, security, and standardization, which all affected passport design.

Printed Passports

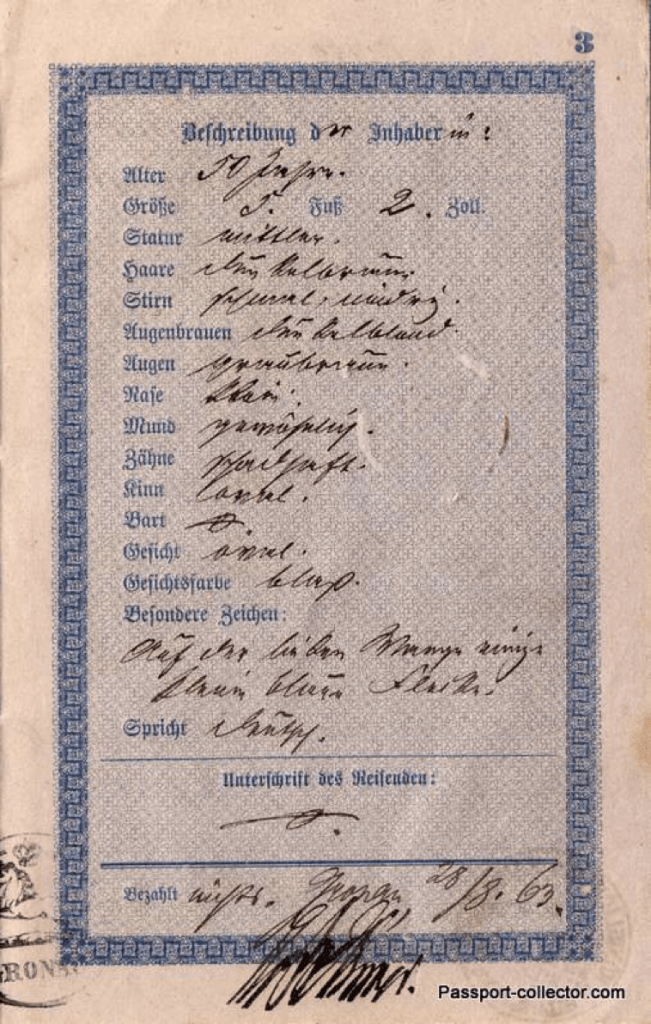

Printed passport forms became more advanced in the 18th century when security features such as embossed text and watermarks were introduced. Several documents were also embossed with a revenue stamp indicating the passport issuance fee to be paid at the local government office. These forms also demanded a much more detailed description of the bearer, including age, height, and a description of their face, eyes, nose, chin, hairstyle, eyebrows, and mustache or beard. Interestingly, ears are never featured in the bearer’s description, whereas nowadays, they are critical characteristics for identifying a person.

First Passport Booklets

I believe the first passport booklets were produced in 1863 in Germany. A full page was dedicated to the bearer’s characteristics (see picture 1). More than 60 years later, only five or six of these characteristics remained in use.

Standardization

The League of Nations passport conferences in 1920 and 1926 led to further improvements in terms of security and standardization. Nowadays, passport design is highly standardized and must keep up with the latest advances in security technology and should reflect the bearer’s national identity.

ICAO

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) recognized the importance of developing machine-readable passports (MRPs) and visas as a crucial step forward in facilitating the clearance of passengers.

In March 2002, the ICAO Council adopted a new standard that requires states to issue a separate passport to each person, regardless of age. These changes became effective on 15 July 2002.

The Passport Photo

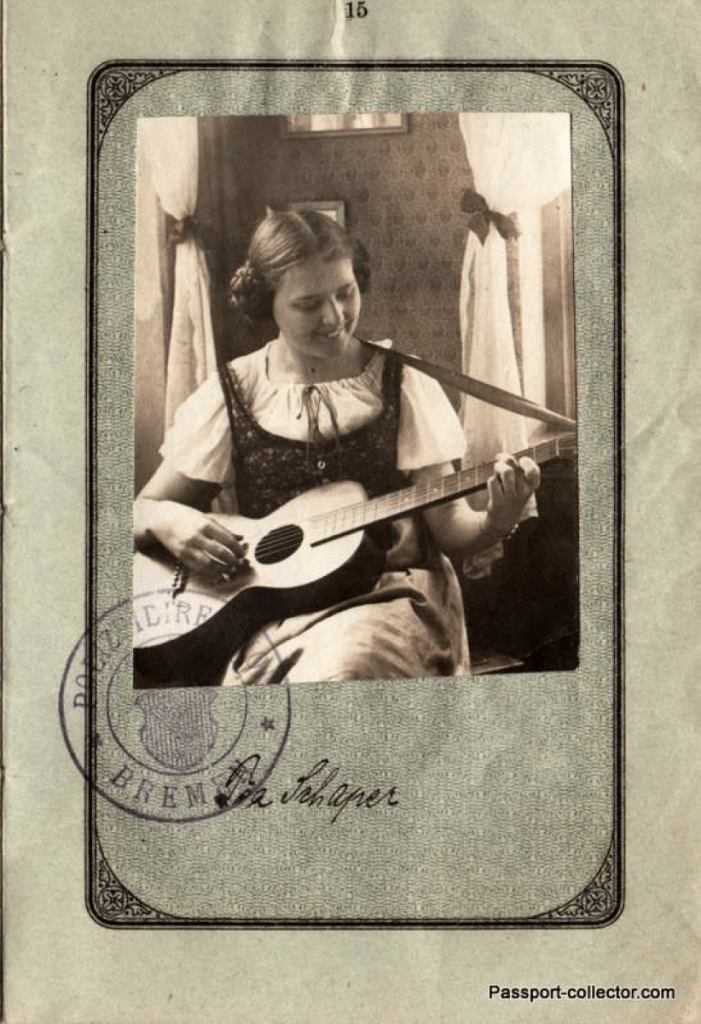

The year 1915 was a landmark in passport history. The circulation of passport booklets increased dramatically, and the addition of a passport photo significantly improved its usefulness for identifying a person. However, standardization of passport photos wasn’t a concern at first.

The passport photo has been a significant characteristic of any issued passport for “just” 106 years. The variations of images were vast when introduced in 1915. The exact date for submitting the passport photo in German passports by law was 1. January 1915. The USA was just a bit earlier, in December 1914.

Introducing a photo into a passport improved the verification of its bearer significantly (in combination with the personal description). However, passport photos were not standardized initially, which gave rise to all variations of curious images. E.g., people standing in the park (full-size photo), sitting on a bench, on a horse, or showing them playing the guitar. Photos with hats were widespread. Also, the sizes of a photograph were not defined, and all measures were possible as long there was a place to mount them into a passport.

The Future

Physical travel documents as we know them today might disappear in the next 20 years as travel, especially air travel, is significantly growing. Our society is looking to speed up the process of travel while increasing security measures concurrently. Nowadays, some countries already issue electronic visas (which you don’t see in your passport). Like facial recognition or fingerprints, biometrics are also significantly on the rise. Your Biometrics might become your passport, and travel authorizations will probably be only in a cloud.

See also:

- The Passport’s Future: Is The Physical Travel Document on Its Way Out?

- Will Passports Exist in 20 Years?

The future will undoubtedly bring new ideas and standards, but that’s the good news for collectors like me, as these items of desire – a classic, handwritten, sealed and stamped passport with its fantastic diversity of passport photos – will become a significant historical collectible of value.

Passports as a commodity – CBI

Several countries are offering CBI (Citizenship by Investment). Some spend money on a condominium or a car; others spend it on a second or third passport. It’s said money can’t buy everything, but surely you can get a passport and citizenship for it. Of course, you need to be wealthy, and people spend up to $2 million for one document to gain citizenship. “My house, my car, my passports.” $2 million would cover the passport fees for more than 30,000 ordinary citizens applying for a passport in their home country.

Does it make sense to hold multiple passports just because you can? E.g., if you are a U.S. citizen, you must, by law, enter and depart the United States on a valid U.S. passport, regardless of age or possession of foreign passports. It is illegal for U.S. citizens to enter or leave the U.S. other than on a U.S. passport.

I like to collect passports too, but mine are old passports. My “historical passport program” is also by investment. But I can assure you it is on a significantly lower level than the figures above.

People investing in passport programs are from countries with limited visa-free travel abilities. It provides certain freedom – the freedom of movement. While governments are earning significant extra income with such programs, there are also critics. Some say it allows money laundering, immigration of “suspicious people,” organized crime, and terrorism. And yes, there have been such cases.

Establishing a Passport Index was a stroke of marketing genius of the CBI-industry to show wealthy investors which travel document they need to cross borders visa-free.

If e.g., the German passport is good for visa-free travel to 194 countries, then I would say it’s a damn good diplomacy work, which should not be underestimated.

The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS) issued in 2014 a research paper with the title “Should citizenship be for sale?”. According to RSCAS, selling citizenship corrupts democracy, and linking citizenship to income undermines European values. They also ask, “Should and could the E.U. intervene?”. These questions came up already in 2014, and now, seven years later, in 2021, they are more valid than ever; and the E.U. took action.

Passport Collecting

The most expensive collectible passport ever sold for $263.000! Passport collecting as a leisure activity is not as common as collecting stamps or coins but it is surely most unusual, educational, and entertaining. Finally, as we can see at the price above, they can become very valuable, just like artwork.

Tom Topol is a passport history expert and author with several publications. His website passport-collector.com and his book LET PASS OR DIE are a goldmine on the history of passports. Tom assisted the U.S. Department of State in Washington D.C. for their historic passport exhibition (From Pirates to Passports), for which he received a recognition award from the U.S. State Department. One of the latest projects was for the oldest watchmaker in the world, Swiss company Vacheron Constantin.